In the autumn of 2004 I got a job as the photographer at Jumpin’ Jaks nightclub in Cardiff, which was a notorious place in South Wales, now sadly closed. Being the official photographer meant taking photos of people in the club, and taking their orders for prints, which, this being before phones had sophisticated cameras in them, was quite lucrative. I met lots of people who’d come into Cardiff for the night from the South Wales Valleys, and I always got on with them well: they were friendly, quick-witted and dry, and always saying to me, you should come up the Valleys and see us. So I started exploring the places people had told me about.

That area, if you don’t know, is a series of long, wide valleys where much of the coal mining and steel industry in Wales was located. Along the flat bottoms run roads and towns famous in British history: Merthyr Tydfil, Pontypridd, Aberdare, Ebbw Vale, and Treorchy and the Rhondda. The steep valley sides and tops, though, are often wild moorland marked by former industrial workings. The Valleys have an incredible history of institutions like theatres and libraries for working-class people being built from contributions from the miners who lived and worked there, paying the Penny in the Pound. Most of the communities were badly affected by the closure of mines and other industries in the 1980s and 1990s, and the area often gets a bad, sensationalised press now.

The first is Ynyshir, and Walsh Street is in Abercynon. I just love the texture and the kind of the way that you can see the kind of skeleton underneath. I like textures, especially when you can see underneath. I love to see torn billboard posters. It’s a kind of art-historical thing.

I found them friendly and welcoming. My visits really started with me looking for old cars in the Free Ads, and ending up in some incredible-looking places. I once bought an Allegro in Newbridge for £70. But I loved the light in the Valleys, and the sense of place is as strong as I’ve ever experienced; it was probably those two things that got me interested in photographing them when I started visiting. I’ve got a friend from Merthyr who said he couldn’t believe I didn’t get my head kicked in, looking like I do (big beard, long hair) but I’ve never had any problems like that, because people are always just interested in what I’m doing. When I went to the Gurnos [a large council estate in Merthyr Tydfil, used as the location for the third series of Channel 4’s Skint] a bloke came up to me and said, quite abruptly: “What you’re photographing?” I just told him, and explained why I wanted to take the picture of the estate. We ended up standing there talking about it for an hour.

I have always found spots in the Valleys that I think of as thin places. The idea of “thin places” comes from the ancient Celts, and the phrase describes a place where the veil between us and God, or you could just say the spiritual, is thinner. In my thin Valley places it isn’t God I feel though, it’s the past; the recent past of the old community relationships that were being forged in the homes and the workplaces, when people believed they were building a better world for themselves.

I was passing by one day when I spotted this boy, and asked if I could take his portrait. He looked surreal standing there with his dog, and the number on his hat. I emailed the photo to him, but he never replied. The valleys have got sheds and garages everywhere. Let people see any bit of land, they’ll put a garage or a shed on there. God knows what’s in any of them.

I need to explain that this is not just about nostalgia, but more a reaction to the sort of “urban renewal” that has obsessed the local authority in Cardiff for the last 30 years. As in other industrial British cities, scheme after scheme has clumsily wiped out streets and buildings people related to, and replaced them with glass and steel structures that you could find anywhere. It is possible to do this and acknowledge your history, as was shown by the Kings Cross development in London or the Angel of the North. In Cardiff it makes you feel as if all that history, all those feelings and ideas, has been written off, which is why sometimes I stand outside an old shop or see a certain detail in a window frame, and feel like I’m looking at a sort of talisman. It comes back to what I mean when I talk about a sense of place.

I didn’t come from Wales originally. I was born in Castleford, in the Yorkshire mining country. My parents split up after arguments about the 1984–5 miners’ strike, and I ended up moving around a lot as a kid. I’m an only child, and I always used to notice we were in a new place because there’d be different roof tiles, or street signs, and when we were driving in the car I’d look out for signs. I remember sitting in the back and looking out of the window at night seeing distant lights, and thinking, I wonder what the people who live there are like? What will they be doing, sat watching telly, or what? As an only child you learn to entertain yourself thinking about stories like that, so I’d draw and paint pictures of them, and think of their stories.

In the valleys everyone needs a car, really, because lots of places are isolated from public rail transport. There’s buses, but buses take so long to get anywhere. The car on the right is a Ford Mustang, in Pentwyn. It never moves. The other is a Sunbeam Rapier. It doesn’t move either. I think the owner tried to put a V8 engine in, but it didn’t work. To me, it feels like quite a valleys thing to just… leave something, to abandon it, you know. Or to put it in a shed and forget it.

My grandfather, a mining engineer and mines rescue in World War II, died in 1946. He was a keen amateur photographer and my grandmother gave me his Voigtländer camera. I played around with that, and then she gave me an SLR for my 17th birthday, and that was how I started, really. I went to Cardiff to study at the Art School, but it didn’t work out. There was this sort of class divide – if you did Fine Art you got all the studios and facilities, but if you did Art and Aesthetics like me, there was next to nothing. I never even had a tutor, just locked myself in the darkroom for three years and taught myself 35 millimetre photography, with the help of one of the technicians. But then I met my partner, and after the course I stayed in Cardiff and got a job in a commercial photography studio. It was after a few years there that I got the job at Jumpin’ Jaks.

I used to drive to the Valleys and take photographs casually for a few years. Sometimes it would be to do a commercial job, PR photos for a new building or a windfarm or something, which was good because it would take you into these corners you might not think to go to. I don’t have the words to say how much I loved it, every place seemed to open up a new view or perspective, or lead to meeting new people. Ten years ago, we moved from Cardiff to live here, in Treforest, and we are very, very happy here. Around that time I began to notice how other photographers, doing stories about the region, seemed fixated on poverty, misery and the bleak run-down streets and buildings; I specifically recall a photo of a run-over fox, as if you don’t get run-over animals everywhere, and the Welsh Valleys are full of murdered animals.

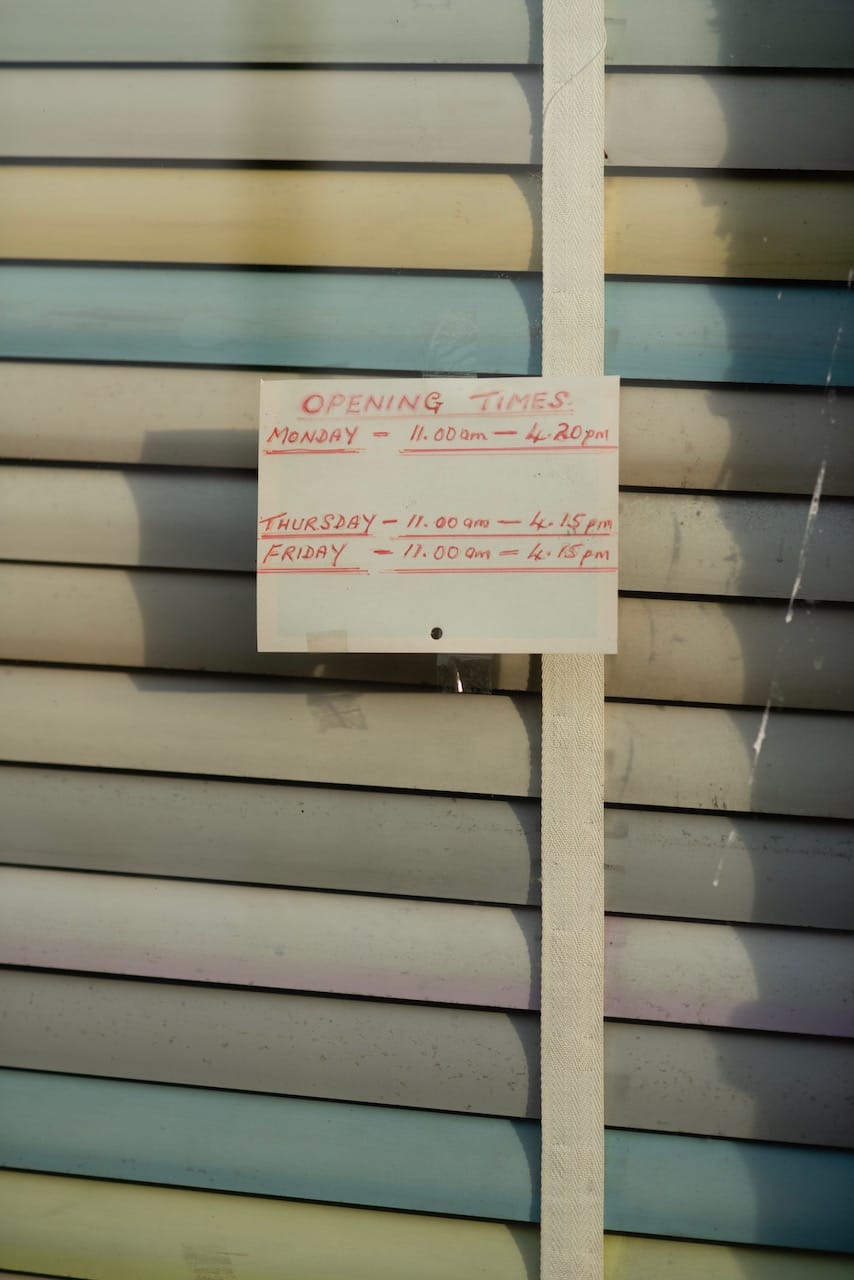

The first is a knitting shop. I just love the opening hours, particularly that five-minute difference on a Monday. What was different on Mondays that gave her that extra time? I don’t think it opens now. The other two are my local hardware shop, which is where I go to buy bird feed. I use it religiously because I don’t want them to shut down basically. In fact, things are working better for them now, because Vinted parcels and that sort of thing are dropped off there. Whenever you go in they’re sorting out all these packages.

It was those photographers who inspired me to try to photograph the Valleys in a way that reflected not just the harder sides of life, but also the beauty and the joy and the humour and the cultural heritage that characterise actual, lived life here. I have a very positive response when I show them, although the arts establishment isn’t keen; my work is often dismissed as “sentimental”. I find it hard not to see in this the imposition of a middle-class gaze in which working-class people are overwhelmed with misery, and lack individuality or agency. It’s interesting that among commissioning bodies, there appears to be far more interest in inviting people from outside Wales to photograph the Valleys than there is in local work. Anyway, I’ve decided to publish my work myself now, and have a crowdfunder for the production that ends next week, hint hint. There’s been a great response, and I have felt pleased to have recorded this most wonderful of the world’s landscapes in a way that its people have enjoyed – and not a dead fox in sight.

Jon’s Valleys book will be published in July. To order a copy and/or donate, go here

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments