The men in my family came to England from Malaysia and Singapore, and once here they were introduced by mutual friends to my mum’s family, who were mixed Punjabi-Malaysian-Irish, and had lived here for years. My mum and dad had an arranged marriage. My only little brother, the princely Rachi, and I grew up in Bedford in the 1980s and 1990s as children of parents with mixed heritage-Punjabi, Malay and a splash of Irish cream. When I was 12 my very pious paternal grandma (or dadima, in Punjabi) came to live near us, and in 1994 my little sister Kally entered the world via birth canal.

I have learned, when asked about my family, to give simplified answers.

My grandfather had a corner shop called Singh Stores in the Queens Park area of Bedford, and my father worked as a labourer in the Brickyard, which was back-breaking work and a hostile environment for an immigrant. The religion I was born into was Sikhism – a monotheistic religion founded in 15th-century Punjab. It emphasises devotion to one God, equality of all people, selfless service, and honest living. My brother and I went to a Church of England lower school, where I loved singing hymns, but it was from my family, community and Gurdwara that I took my spiritual sense.

At the heart of that spiritual community were the Punjabi and Malay-fusion Chinese, Tamil and Portuguese dishes that each family would cook for each other, dishes that captured the colonial and migratory history of Malaysia. Gathered around the modest narrow rooms of our small Victorian rows of houses in decaying streets, we shared this food, and consumed the lushness of the finger-licking memories of our heritage, our homeland.

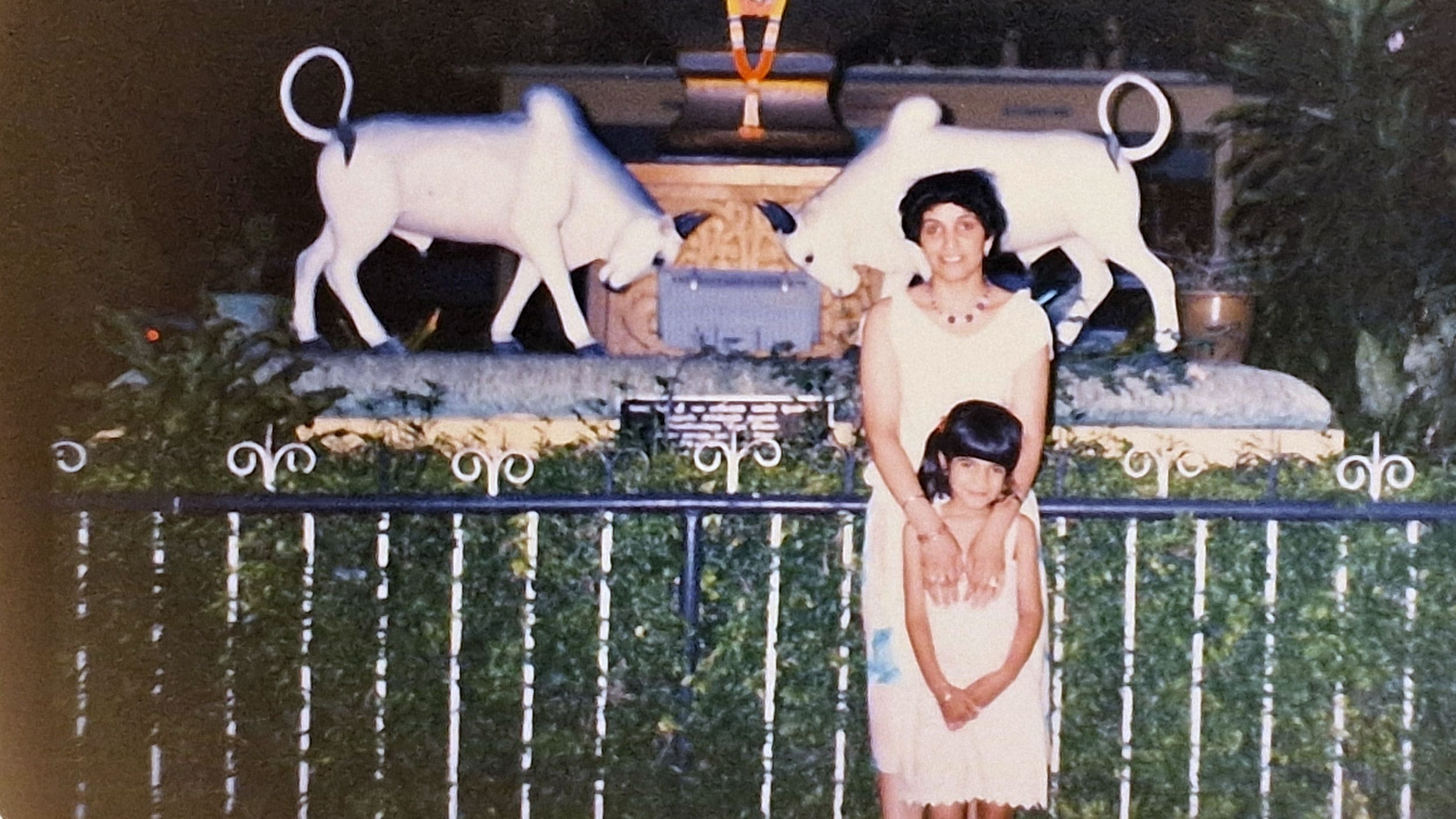

We would usually go once every few years to Malaysia and Singapore (the more affluent of the two countries), where we would stay with one of my dad’s seven sisters. My mum’s cousins all resided in Singapore. The food we ate on these visits was joyful, and it stands out in my memory even now. Curry laksa noodles from street and store food courts; Hainanese chicken rice; sweet, piquantMalaysian limes; fresh rambutan and lychee bought from markets and wrapped in transparent red plastic bags. A particular favourite was air sirap, the fragrant drink usually consumed at Malaysian wedding parties. A saccharine streak of bubble-gum pink inking the water, the syrup is brewed with rose petals and, when concentrated, it has a magenta hue. Glassy ice is poured into the glass, along with spices, pandan leaf, ruby colouring, sugar and delightful condensed milk. I used to have mine with fresh coconut juice and extra sugar cubes.

It wasn’t just the colours and the flavours of the food that made it memorable. It was also the preparation – so often a collaboration, a familial drama, and always an act of love that was bone deep, marrow deep. It began as soon as we arrived. After the exhaustive, sticky 14-hour flights from the UK in July, I would have a sumptuous nap under the turbine-like fans, lying on one of the charpais that stood on the chilly tiled floor. My Bali Puha brewed some sweet, cardamon-laced Punjabi chai in her patali, silver and well worn, with the patti aromatic as fuck. As well as curry puffs, and kaya with thick and glutinous rice sesame balls, and jian du.

Sometimes we visited Port Dickson and its secretive little Edens like Panti Tujung Tuan (Blue Lagoon) to see my Kinti Puha and Dastar uncle. We visited Monkey Beach, where my Kent Puha was. There my family, especially my dad, loved to cook Malaysian crab curry. They looked out for the black, or mud, crabs that are mostly found in estuaries and among the mangroves, shell colours varying from a dense mottled green to a deep brown. My dad loved them because they had such succulent meat. He bought them still alive with their claws tied, then banged each one over the head with a hammer, cracking their shells and then tossing them in the handa or sabji with lots of spicy thari.

The recipe was my family’s. Usually in the quiet heat of a clammy afternoon, the scent of crab curry would rise like incense from my grandmother’s kitchen — a potent concoction of turmeric, cumin, and coconut, wrapped in the acute sweetness of curry leaves and mustard seeds popping in spitting oil. She was Punjabi and my Dada Malaysian and, in their kitchen, borders blurred. The curry she made was a fusion not found in cookbooks — mud crab marinated in salt and golden turmeric, then gently lowered into a masala so deep and red it felt just born. Tomatoes melted down with garlic, ginger, and green chilies until they became the soul of the dish. Then came the coconut milk — lush, cooling, with a whisper of fennel — and the crabs, turning orange and defiant as they simmered.

We’d eat with our fingers, the spice clinging to our skin, the sweet meat of the crab coaxed from its shell. I suckled the masala from my wrists, laughing, alive. Years later, recovering from ovarian cancer, I wanted to eat like that but couldn’t, because I thought people would judge my etiquette — but the memory of that curry was its own medicine

One oily, almost moonless night, when the stars were silver balls of acid fizzing above the indigo blue sky and I was just seven years old, my family gathered on Monkey Beach: three uncles and three puhas, my mum, my dad, my brother, four cousins and myself. My Kully Puha was renting a chalet on the beach. We were lit up by a furnace-like bonfire we had made. The bonfire was blazing flaming gold, nectarine orange, and claret, and if you stared long enough you could see mirages: apparitions of nuclear yellow and apocalyptic blue.

“Ah Nitty, stay away from the kebarkaren!” called my Kent Puha. I mouthed the words as if mimicking her. I was wearing an all-in-one ThunderCats romper suit and sucking on some sticky fruit jellies. At her call, I ran to her and jumped into her lap. I snuggled into her jelly belly and bosom. I was tired, drool and fruit-jelly saliva oozing from my pert red mouth.

“Hantu in the fire, lah!” my Peritah uncle laughed, bottle of Tiger beer in his hand as he sat cross-legged in casual blue shorts and a counterfeit Armani t-shirt, looking magnificent with his onyx beard and dastar in menstrual red. Peritah was my favourite uncle: jolly, kind and trusting.

They had caught some crabs, although I didn’t know it was for a curry. Watching the glittery bonfire, I was blissfully ignorant of their fate, despite the big cast-iron cooking pot and culinary utensils glinting in the firelight. I watched the crabs squirming on the beach in a red plastic tub, their claws bound with red plastic ties. Suddenly one, a fiddler crab, escaped and zigzagged towards me across the beach.

When it stopped, uncertain, my uncle scooped it up expertly.

“NO!” I yelled. “DON’T KILL COUNT CRABULA!” I began to bawl my eyes out, big tears spilling down my cheeks, viscous snot running down my face. I wiped the snot with the back of my hand, and my uncle’s black eyes looked at me with pity.

“Ok lah Su-nee-tha, you keep this ketam as pet,” he said, placing it in a separate bowl.

I hugged him and smiled at him in hisdastar, my hero. I would have a pet – a haiwan pehilaraan – all of my own! The wind had softened. Inhaling the salt air, I stood over the fiddler crab. I asked my uncle to take the ties off Count Crabula’s pincers. I pointed excitedly at the scissors. Count Crabula had also somehow acquired a little bow on one of his legs made from the plastic string food hawkers used when wrapping their goods in cellophane bags.

I watched the crab for a while, trying to feed it bits of seaweed. My Kent Puha humoured me, and looked for more seaweed. Gradually, I lost interest and went off to play, leaving Crabula to his own devices. After a while, we all sat down together to feast on the delicious curry.

Later, in the glittery hinterland of Monkey beach, I spotted a charred crab claw with a bow attached. Realising that they had killed and consumed Count Crabula, I ran into my Kully Puha’s kitchen half-crying, half-screaming.

“You ate my pet!” I sobbed, swamp-green snot running over my lips.

My Kully Puha, standing in her maxi loose batik nightdress looked pained. She hugged me. “Your crab escaped,” she explained. “And one of us plopped him into the curry.”

“It was your Charan uncle, he was a little drunk dahhling,” my Kinti Puha said in her sing-songy accent.

I was distraught, but suddenly my Peritah uncle was there. He rubbed my back and squeezed my hand.

“Darling,” he said. “We have one or two spare live crabs you can set free!” He wiped away myears with a screwed-up tissue which was crisply clean.

I trusted him , so I knew it was going to be all right. Later, he carried me in my pink swimming costume to the edge of Monkey Beach and allowed me to pour water and two bright-tangerine crabs into the ocean.

Short glossary

I use Malaysian and Punjabi words in my work to reflect my experience. In case you don’t know them, here’s a list.

Punjabi

- Charpai – traditional Indian beds made with wooden frames and woven rope or jute surfaceDada - grandfather

- Dastar – turban

- Gurdwara – Sikh temple

- Handa – heavy pan

- Hantu – ghost

- Kebarkaren – fire

- Kaya – coconut jam

- Patali – saucepan

- Patti – tea leaves

- Puha – father’s sister; ‘aunt’ is the easiest translation. Unlike in English, the name goes first, so Bali Puha means Aunt Bali.

- Sabji – curry

- Thari – a soup-based dish

Malaysian

- Ketam – crab

- Haiwan pehilaraan – pet

- Jian du – a deep fried Chinese pastry made from rice flour

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments