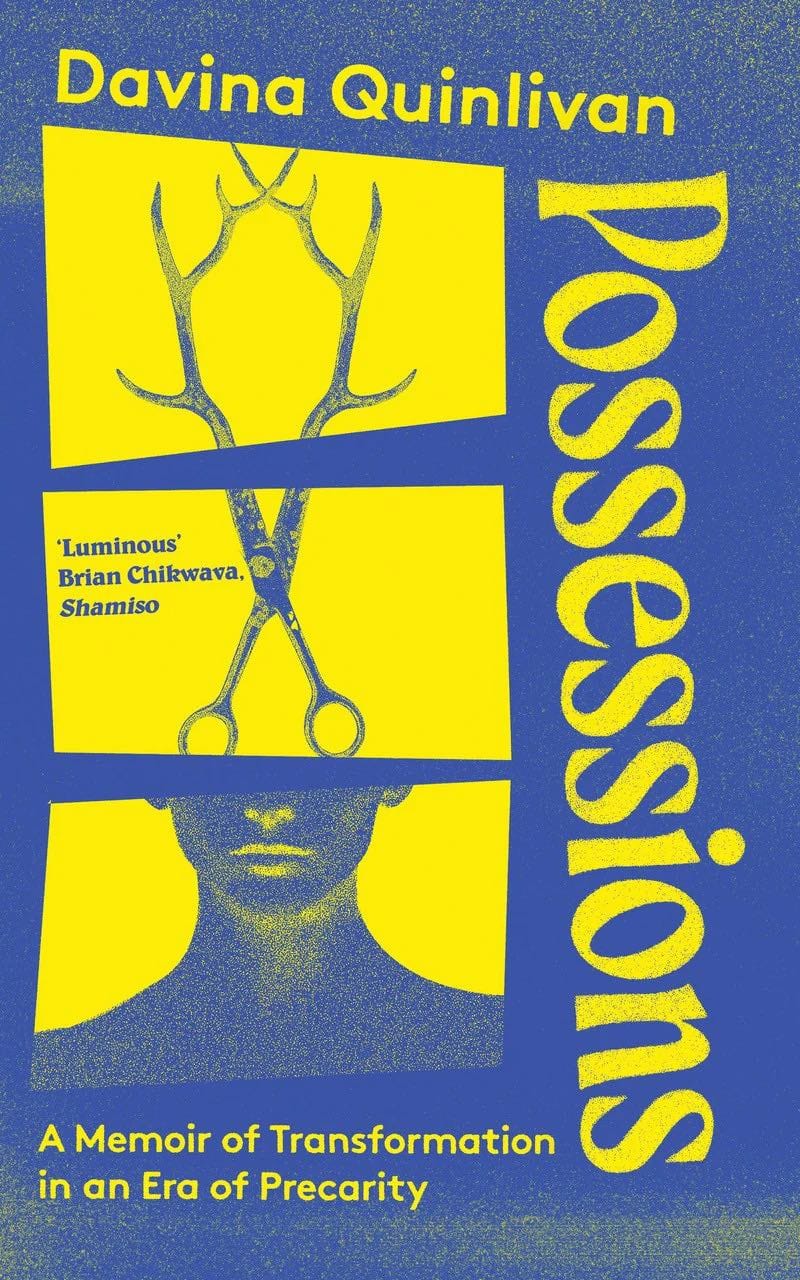

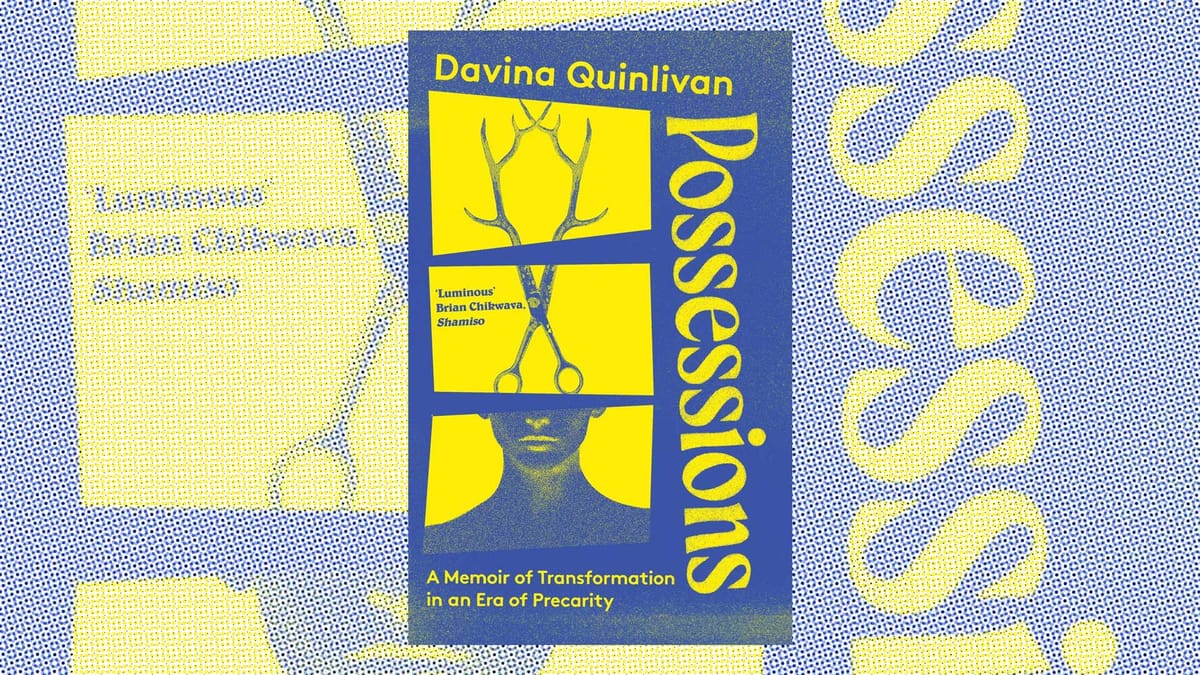

Davina Quinlivan is a research fellow in the department of English and creative writing at the University of Exeter, and the author of Shalimar, an "imaginative memoir of migration and finding a home" published in 2022. Like Shalimar, her new book Possessions: A Memoir of Transformation in an Era of Precarity combines different forms and styles of writing, and draws on her Anglo-Burmese heritage and her experience growing up as a working-class child in Hayes, west London. The Bee caught up with her to talk about class consciousness in middle-class work environments, walking, taking control of your work as a writer, and how her cultural heritage enabled her to forge a stronger sense of herself.

Richard Benson: Davina, in Possessions you movingly describe growing up in Hayes in west London, where a lot of people work at Heathrow. The way the community was clustered around one place of work reminded me old working class industrial communities where everyone worked in the same place. Do you see similarities there?

Davina Quinlivan: I’d not thought about that. But everyone did work at Heathrow! It was one bus stop or a 15-minute drive for most people. I worked at the WH Smith in Terminal One between the ages of 16 and 18. I’d finish studying, and then I would go and do that. My dad worked in a food distribution company warehouse. I just grew up walking around the aisles of pallets. My mates used to get things from the duty free, because their dads worked there in security. Everyone always had plenty of CK One.

RB: How did it feel doing that sort of work in a place where people were jetting off all over the world?

DQ: In a weird way it was exhilarating, because there were people travelling to these amazing places, and you’re seeing all this buzz and this business. It was quite interesting to be in this gateway to places that I was never going to go to.

RB: You explain in your memoir how you went on to become an academic, and then describe how the precarity of short-term contracts, and the remote working undermines your sense of yourself. It’s that debilitation that eventually leads to you drawing on your Anglo-Burmese heritage to reclaim your mind and body. It seems that you revere your work but find modern working conditions destructive.

DQ: Yes. It’s like a sacred thing to be able to teach and to work in that field that’s about knowledge and, to use a bigger term, enlightenment. But academia is much more open about being a business now, and that’s changing the whole system. The values within that system are being rewritten.

RB: Working in higher education is seen as a middle-class occupation, but do you feel the use of short-term contracts has weakened some of those old certainties and confidence?

DQ: Yeah, but the confidence has been eroded in every area of our lives, hasn’t it? I do write about people who do job interviews, and because some people may have had a more privileged upbringing or may have just a different way of operating, they already know that they’re going to turn down the job so that they can negotiate their pay in their current job. I think that’s all bound up with class and confidence. But there are very few people who have that kind of confidence now. I certainly don’t. I feel like we’re falling through all the levels that used to be in place. We don’t know what’s left and what’s right or what’s up or what’s down. Eliza Filby talks about this in Inheritocracy.

RB: Yes, security, or the lack of it, seems like a key element of class status now.

DQ: In a way, the idea of having a working-class background and being more kind of family- and community-oriented gives you a sense of security, but the precarity and the short-term contracts mean there are all these holes … I talk a lot about holes in the book because I see the gaping holes and threads coming undone in everything.

RB: You talk about your dad being a grafter …

DQ: Yes, he tells me I’m not a grafter, and I feel guilty because I’m not doing what he did. Because he died when I was 27, I’m trying to work out if he would think I’m happy. What would he want for me? He was a prisoner of war as a child, so he wasn’t really about material achievement.

RB: There is a strong sense in Possessions of you managing your different, intersecting identities. Did that influence how you write the book? You have called it an “imaginative memoir”, and it combines conventional memoir with elements of mythology and poetry, and a non-linear narrative. Plus, James Roberts’ illustrations.

DQ: Those identities are all coexisting all the time, but I sometimes become more aware of them when I’m teaching online, or in job interviews. Because it’s very, very much about being a woman. It’s very, very much about being a mum. It’s very, very much about being a woman of colour. And then they’re asking me about EDI … And this is all happening while I’m in rural Devon. Sometimes one thing is more powerful than the other. It feels like I have to keep wondering, and the more I ignore those things, the more painful it is.

I talk directly about class, about being a woman and also about my ancestors, but it also shows in the book in that there are set pieces where a sort of magic happens. I think the passage in which I meet the witch in the cave speaks to all those areas. It manifests in the weirdness (laughing).

RB: That makes sense to me as a reader, because it seems that you had to invent new forms to express yourself, because you were talking about things that are not often expressed. There’s not a set of rules you can use.

DQ: Well, not wanting to sound too arty, or like we’re doing a creative writing lecture, I feel I have deliberately chosen that form because it’s the only way to write it. I think that’s the strangeness that I’m trying to get out.

RB: It seemed a very inward-looking book, yet also very interested in social relationships. Were you deliberately trying to get that balance?

DQ: I keep thinking, is it a bit sad because it’s just me going around in my own mind, but it’s not, because there are so many presences in there. I worked in a cast, or a collective community, so even though it feels like it’s memoir, it is still about communities.

RB: I find a lot of working-class writers are looking for a different way of writing about their experience that doesn’t really fit into conventional narratives, and one recurring example of that is people who want to write in a collective way, about and for others. They want to write about the community. You can see it in books from The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists to Lark Rise to Candleford to The House on Mango Street to Trainspotting.

DQ: That feels like something I was trying to do. Writing memoir, especially as a working-class writer, is something that means you come under scrutiny. Is this a working-class narrative? What kind of story are you putting forward? There are expectations. And it’s intersectional, isn’t it? Because it’s also about capitalism, colonialism, and ethnicity and race and sex and caste and all those things.

RB: Were there any working-class writers that you feel particularly influenced by?

DQ: I think the better way of answering that is, I just want to read more around writers who’ve had either similar experiences, or very different experiences, which haven’t been just broken down by the class system or who have found other ways to be. I read poetry, and I really like Ella Frears. Her poetry is great, and she writes about class a lot. As I teach film, could I add a working-class film recommendation? That would be Clio Barnard’s The Arbor.

RB: I was struck by your point about borrowing and becoming, which gave a class context to your thinking about identity. There is a moment around halfway through the book where you say “Becoming was rarely within the reach of my own vocabulary. Becoming was not something I understood. I was born grateful, or ignored, never entitled. I was always ready to beg, borrow or steal by any means necessary. I borrowed but I did not become.” I felt a lot of people would recognise that experience.

DQ: Yes. Magpie, raven or ancestral goblin? I think we have to borrow a lot, all the time.

RB: What was your process for writing Possessions?

DQ: I started writing the opening section, which started off with about 5,000 words, in December 2023. I had the first section, which grew to about 10,000 words, by January 2024. It’s almost like books all have their own kind of rhythm or, you know, they’re all a different kind of song, and I immediately felt the energy of what I was writing. I recognised its tone. And I felt the song within this was strong. It all came quite quickly, and I had a whole draft by around the end of March 2024. That is not normal and I recognise that it’s quite speedy, but I did have that feeling that I knew where it would go.

I sent it to my agent, and she had an instinctive feeling about it and saw it for what it was straight away. But again, I want to say that that’s not a standard practice. Books happen in their own way. They develop in their own way. And I’d already set that in motion with my previous book, Shalimar.

RB: Do you have a particular place where you like to write?

DQ: Probably 90% of it was written in the bedroom, facing a window. I write about the window in the book. It’s important because I could just look out [at the countryside]. Sometimes in the spring, I’d open the window and I could hear the sheep.

RB: And then, in September, your publisher bought the book…

DQ: Yes, and I’ve been very, very fortunate in that they made me part of that whole process – they’re not an imprint of Duckworth, but I think working with an indie publisher has given me a lot of agency, and I really value that kind of agency that an indie publisher gives me. I feel working with indie publishers does tend to give me that opportunity to world-build around the book. I think writers need to envisage where they want their book to live.

RB: You mean everything from how it might be packaged, how it might be sold, where it’s going to be in the bookshop and things like that?

DQ: Yes. I think it’s important for us to get tooled up to have knowledge of how the industry works. I know it’s time-consuming. But I think it’s important to understand what’s going to happen to this material object that you’ve created.

RB: That sounds like a demystifying approach.

DQ: I like that demystification. I can’t talk enough about how important it is to understand the politics, the dynamics and the power systems at play in the process of publishing. If you can understand the dynamics, and you can understand what each person’s role is and what they need to do, and to have trust.

RB: In the book you talk a lot about online communications, and particularly the online video meeting. You look at the etiquette, the subtle power displays and how the experience plays out differently for different classes, ethnicities and genders. There’s a telling moment when a man in a senior position is brought a cup of tea by his wife …

DQ: The book is partly about what all that is doing to us. Take the job interviews I write about. What the hell is going on there? You know people say, “Oh, it’s really windy outside,” or comment on the rain – but we’re not in the same room. What am I supposed to say? And you can’t even have that bit where someone gives you a glass of water. And interviewers can really scrutinise your micro-behaviours in a way they wouldn’t in person.

RB: Do you feel the use of video meetings entrenches or gives away any class divisions or differences?

DQ: It probably benefits a lot of people because they can detach themselves a little bit further and not be physically present, but have control and at the same time be an all-seeing, kind of godlike figure, because they can check their emails and messages at the same time. They can check their calendar, they can check what’s happening on TikTok and probably no one’s going to know. You can have several conversations at the same time. There’s an interesting power structure there because it tools up people in powerful positions even further. I think it suits a lot of middle-class men to work in that environment.

The online system is quite enabling. And it means you can also relinquish any kind of real physical human responsibilities that you might have.

RB: You dedicate the book “to all those who were present”. Is that a reference to people being fully present – or not – in meetings?

DQ: Yes, I mention it at the beginning because there are a lot of people who were not present. I write just being present again. And the book does reference Marina Abramovich and her The Artist Is Present show.

RB: When we look at what’s happening in the US now, the act of simply being present and appreciating another person as a human being seems important.

DQ: I think it has quite a Marxist indication. There is a brilliant book called Marx for Cats by Leigh Claire La Berge. I’d recommend it. It makes a case for the cat as a kind of icon for Marxist logic. In the book I say the cat is never on the side of power and talk about a cat on a Zoom call just walking where it wants. And I think that connects to what you’re saying: it’s about the idea of the artist and paying attention and being present and just sitting in that space with someone.

RB: Yes, with no one acting out someone else’s script or expectations. One of my favourite parts of the book was your analysis of how white male academics construct an idea of objectivity, or neutrality, that hides their class biases, and the micro-behaviours used to assert their power. Reading the book, I could sense your frustration.

DQ: Yes, to be in that world is to notice micro-behaviours. Things like bringing your pet cats into a meeting. I feel I don’t need to do fiction, because there’s so much absurd behaviour in reality.

I felt such anger about this – I think that’s what drove the book. I was increasingly faced with these absurd and decentring, obliterating micro-behaviours, which never stopped. I thought, is it only me that’s noticing this? And then decided, well, you can either be completely ground down by that, or you can bear witness. In the end I felt I could be grateful for understanding the ethics that are at play here.

RB: Just thinking about the future – what would you hope for from this book?

DQ: Part of it is that I just want to sit in a room and listen to other people. I hope people say, “Oh my god, I’m so glad you said that,” or “Yeah, that’s what I thought.” Because I want that kind of dialogue with people. It’s not about just sitting there and reading, but getting people to have that kinship and understanding all the complexities. It’s intergenerational as well – I feel speaking across generations is important, because the logic of capitalism is that we’re not supposed to be intergenerational.

I want to meet more people, more women in particular, who’ve had the things I write about happen to them. More generally, I’d like that sense of connection to the way that we think about the living world, and climate, the connection to the British empire, and Britishness. I really want to lean into the Britishness of it, celebrating the kind of Deep England that my parents might have imagined as kids when they were living in India and Burma. Often Britishness is portrayed as just one thing, or just one note, and I think it can’t just be one note. I think that it’s important to understand the reality of what we all face, because we’re all living under that cloud of capitalism, with everything being driven by the rules of commodity, everything being about what we’re purchasing online, and our dreams being curated by Instagram.

RB: It feels like you’re coming back to being present and making genuine connections with people.

DQ: I’m really interested in the process of deep listening. We’re not really doing that anymore as a society, partly because online communication is very performative. It relates to Walter Benjamin, and the way that he talks about in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. I think it’s important for people to really have a conversation and to talk to each other, with stops and starts and breaths and coughs. It’s just sitting with someone and just experiencing their energy. About loving attention, and a kind of loving gaze.

An extract from Possessions: A Memoir of Transformation in an Era of Precarity can be read here.

Quinlivan’s essay “Why I Write Imaginative Memoir”, published by the Women’s Prize, is here.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments