‘In that memory, I am good at something, and it is a bridge. I can hold it in my hands, move myself through space. It is real and not real. It carries me away, for a little while.’

Carmen Maria Machado, Critical Hits, Introduction

Growing up working class, home was a contradiction. Something I struggled to explain easily to people who grew up in one fixed place. It felt like longing; sometimes safety. But it always felt temporary.

My upbringing was unstable. After my parents divorced when I was five, I was caught in a custody battle. Though my father’s contumacious and reckless nature made him unfit for parenthood, he somehow managed to manipulate the care system to keep sole custody of us. This left me and my brother at the mercy of constant moves and changes. Then, during the weekend, I was at my mother’s house on the outskirts of Leeds.

According to statistics, in 2024 more than 150,000 children were living in temporary accommodation. This was an increase of more than 14% since the previous year.1 Even writing out ‘according to statistics’, I felt these figures lose their meaning. One of the problems with statistics is that they don’t capture the nuance of the experience. It’s sort of like reading labels for the food you’re eating without the memory of the taste. We need real stories to understand the impact. It’s not that we don’t have enough houses in the UK: it’s because they are too expensive. Working-class people are moving around this small island and filling houses up to overcrowding. Social housing access is dropping, though, at an alarming rate, while private renting is increasing in price. It’s about the profit margins, not the people. I know: both my parents struggled to keep up with it because of their circumstances. So my home was constantly changing.

My mum waited months to get a council house and, once she moved into it, she tried her hardest to make this a home for us and to get us back into her permanent custody. This meant adding more ornaments and furniture to the house, repainting the walls, and having access to things she might need. One of those things was a computer. She had bought it to study a new course in the hope she would get a job she enjoyed, so that she would eventually rely less on benefits. One day, in a charity shop, I found a scratched copy of the Sims inside a small square of plastic. She begrudgingly bought me it, but as she kept the computer in her bedroom, sandwiched between the clothes in her wardrobe, I was given specific restrictions on the times I could play.

The back of the computer monitor extended the length of the wardrobe. It was cream, stained and glowed in the shadows. The sound of the PC’s dithering modem was meditative. As I put the disk in and the tray closed, I watched the Sims introduction video, mesmerised.

I remember the Sims’ loading screen. Glowing blue letters against a background of dark blue. A small roof, windows and chimney above the letter M. As I loaded up the tutorial, Bob Newbie grumbled at his wife. The tutorial instructed me to address both of their needs. I realised quickly that something as simple as deciding what a simulated person decides to eat for breakfast could be thrilling. I went to Create a Sim, decided the outfit my own Sim would wear. I picked their personality through a series of pre-determined traits like ‘Active’, ‘Playful’ and ‘Neat’. Then, the game gave me a select amount of money to start with, to build their house.

The Sims was released in 2000, and was marketed as the life simulation game. You get to create a simulated person, decide what they wear and what job they do. You control their daily life and get to build and decorate their house. Pixels interlope as you plop down the walls first, a small patio in cream. Decorate each wall with a pattern. Cycle through furniture. Get the necessities. Then, you realise: you can’t afford the TV you wanted from the menu. Should you delete a window? Opt for the tattiest couch, with stains on it?

You zoom out, look into the other neighbourhood houses. Your Sim’s house has nothing on the Goth Mansion with its three floors and perfect garden. You flick through the house with a growing longing and a question. Where did they get the simoleons2 for something so perfect? Mortimer Goth stands in his garden, staring at the old gravestones and his generational wealth.

You flick back to your own Sim. They wave and mumble at you as they try to cook using their cheap microwave. A fire breaks out. You start to panic. Cheap furniture is more flammable. And you can’t afford a burglar alarm, so your Sim is robbed that evening, and their bookshelf is gone so they can’t improve their skills. They miss their bill payment and a repo man comes around and takes their coffee table. Poverty can be so punishing.

I didn’t understand why I had to leave my mother’s house during the week back then. It gnawed at me, the desire to send my Sim off to work so I could keep improving their house. While the rest of my childhood was chaos, I just wanted to keep building a room of my own, virtually.

It was when I was about this age that my home with my father became a moving door. First, we moved in with one of his girlfriends. She used to spend a lot of her own time drinking cans of beer and staring at the neighbours. When they broke up, we had to live with him in a bed and breakfast above a fish and chip shop for a few months. Then there was a high-rise block of flats. Finally, he decided to move back to the small town in Yorkshire where he had grown up, and where I eventually went to high school. At first we lived with my grandparents, then he found a council house close to our new school. I remember him being excited about having his own home. He could never hold down a job because he believed he was too punk for it. But I think he still liked the idea having a place to finally settle near my grandparents.

So I knew at an early age what it was like to constantly move around based on circumstance. Doors led to corridors, reflecting lights inside a fun house. The word ‘home’ started to catch in my throat. Each week was a strange new surprise but, by contrast, my weekends with my mother felt safe. There was a warm glow in the living room. As the years passed, she kept it the same. The old computer, still rattling and gathering dust in her bedroom, was passed on to me. I managed to get my hands on a copy of The Sims 2.

The Sims 2 had better graphics and more stories inside it. My mum’s old PC struggled through the loading screen. Vibrating blue tiles with a bar at the bottom, inching forward. Then cut to the introduction. I first looked at the Broke family in Pleasantview, intrigued by their story but then quickly deciding it was too close to home. So I chose a different neighbourhood. My new view was a fly over of Strangetown, which is one of the neighbourhoods you can move into in the base game. There was a crashed spaceship inside a crater, steam rising from the glitching pieces. Then stones arranged in a circle, spiking from the desert floor, one of them in the shape of Will Wright [creator of The Sims] wearing glasses. Then rows of houses, gregarious mansions and small bungalows clustered together, surrounded by barren sand dunes. Green diamonds glittering over some of the roofs. I sat in my childhood bedroom and clicked around the houses frantically, the fans in my PC whirring with a clicking fatigue.

I moved my first Sim into a nice one-bedroom townhouse on the dual carriageway, which was called ‘The Road to Nowhere’. My Sim started to ask questions as they met the neighbours. I wondered where Bella Goth had gone. Why there were barracks in one of their houses. Why one of the men was pregnant with an alien. Why those suspicious singletons had a telescope on their roof. Strangetown had its name for a reason. I was glued to the screen and cycled through each of their memories and tried to find an answer. It was a parable. A story I wanted to piece together.

I thought to myself, ‘I wonder what it’s like to live somewhere with so many strange things happening.’ Then I thought about the town I had moved to with my father. Down the staircase, out of his new council house and into the streets, terraced back-to-back houses lined up all the way to my high school. Only the local shops to interrupt them, where teenagers tormented the shy kids with slurs and circled around them on their BMX bikes. The looks on the faces of the people walking around. My father’s friends and their camouflage parkas, broken in their livelihoods and chanting Oasis lyrics with roll ups. The back streets with furniture strewn across them, pylons in the fields and burnt tires in the train stations. Market stalls that sold antiques and bike parts. The pasty shop and the butchers. A street of terraced houses built for the miners and paved with gravel. Fields with murky puddles, stolen shopping trolleys tipped into the rivers. Empty forests with tarps swaying in the branches and needles discarded in the grass. A tip for scavenging parts and then a motorway beyond it, rumbling with the urgency of an escape and that feeling that ebbed through me – that I didn’t belong there. I wondered if my Sims in Strangetown felt the same. Like watching horror to assimilate with anxiety, I felt safer exploring the strange town in my teenage bedroom than the one I was living in.3

Later, I tried to make my dad’s family in Create a Sim, and build a house for us all to live in. I made my grandparents, my dad, my brother and me. When I moved them in to a house that I had meticulously replicated, they all stood within the grey walls and argued at each other in Simlish about the ugly furniture and lack of decoration. That’s when I went back to creating my own storylines and houses based on my fantasies. The mirroring was fractured.

By the age of 14, I was already thinking of escaping my own Strangetown. I was gay and it didn’t feel safe. I wanted better things, more choices. A degree. I had fantasies of living in the city and doing something exciting. I struggled with where I was living and decided I would just focus on my studies as a vehicle to get out. My dad had started finding bits of computers in scrap piles. This was his new obsessive venture that he thought could make him lots of cash in hand on the side, only later realising people weren’t willing to pay high prices for PCs with rattling old parts. Sometimes if we passed skips he would find old PC parts and bring them back to the house, like a magpie. A fan. A wire.

I asked, begged, my father to build me a computer that was powerful enough to run The Sims 3. Told him how I would be so happy, wouldn’t need anything from him, if he could just help me build something that could get it to work. So we went out skip diving together until he had all the pieces to make me a computer. He painted the case using green spray paint in the back garden, while drinking a bottle of cider.

Globs of new paint had dripped across the disc tray of my new PC as I put the copy of Sims 3 in to play. Cue the opening credits and glowing memories. Small, virtual people and their beautiful lives so far beyond the world I was living in. In the bask of the loading screen I waited. Prayed all of the other parts would hold out. The warmth of the air rolling through my bedroom and the small whirring noise. I smiled. In the hours inside my bedroom, when things didn’t feel safe outside it, I decided I would make homes that did.

Eventually, I moved to live with my mother, but I kept building different versions of my dream home. I even spent some time making storytelling videos in Sims that were some of the first pieces of content I put on the internet. I had a slightly viral video about a sad death where Alexandra Burke’s version of ‘Hallelujah’ played in the background.

I played out dream lives of travelling the world through The Sims 3: World Adventures. Imagined a life in a city apartment with The Sims 3: Late Night. Made a version of myself in The Sims 3: University who rode a bike around campus and studied Communications. Symbiotically, I went interrailing across Europe, then moved into university halls to study. I moved into a maisonette with some other students. Half of a house below a rehabilitation centre. A groundfloor flat in Manchester. Three more flats in Manchester. My restlessness persisted.

My environments had changed and the feeling of needing to escape had mutated with it. Things felt safer, better, but I was still searching for something. Better cafes, better choices, better options. Like my other friends in their twenties, I was moving to discover. Moving because you are forced to is different to moving out of choice, but it can bring some of the same feelings up. It can catapult you back to a familiarity. It feels a bit like when I moved different bits of Sims furniture. If something doesn’t fit quite right, why should I settle?

I’m not encouraging or needing excess here. I’m talking about having choices and, at the root of it for me, safety. Until then, or until I can rub this stain out of me, I’ll probably keep moving. In all iterations of The Sims, there are NPCs (non-playable characters) called ‘townies’. They are fully fleshed out characters who move between different lots and interact with your playable Sim. Except they are always moving. No fixed address, but sucked into a vortex when they aren’t of use to the story. Sometimes I think back to all of the moving I’ve done and it feels not dissimilar to this. I am not an NPC. Sometimes though, I have people ask me where I’m living now when I haven’t seen them in a while, as if they are already expecting it to be different.

Sure, my Sim might spend years of their life sucked into the vortex after their carpool picks them up, but eventually they might be able to make a home that’s perfect for them. Are they a green thumb? They might save their wages and spend it on a rack of plants. Are they a chef? They’ll save up simoleons until they can buy the most useful oven. In real life, I can’t sell a window or the pool ladders when my bills are too high, even though there’s been points I probably wished (or needed) that to be the case. I could get money for my Sim using the motherlode cheat for my sims, but it feels less satisfying. Life is a lot like this. It’s capitalism, yes, but for people who grew up working class, a dream home won’t come from a cheat code.

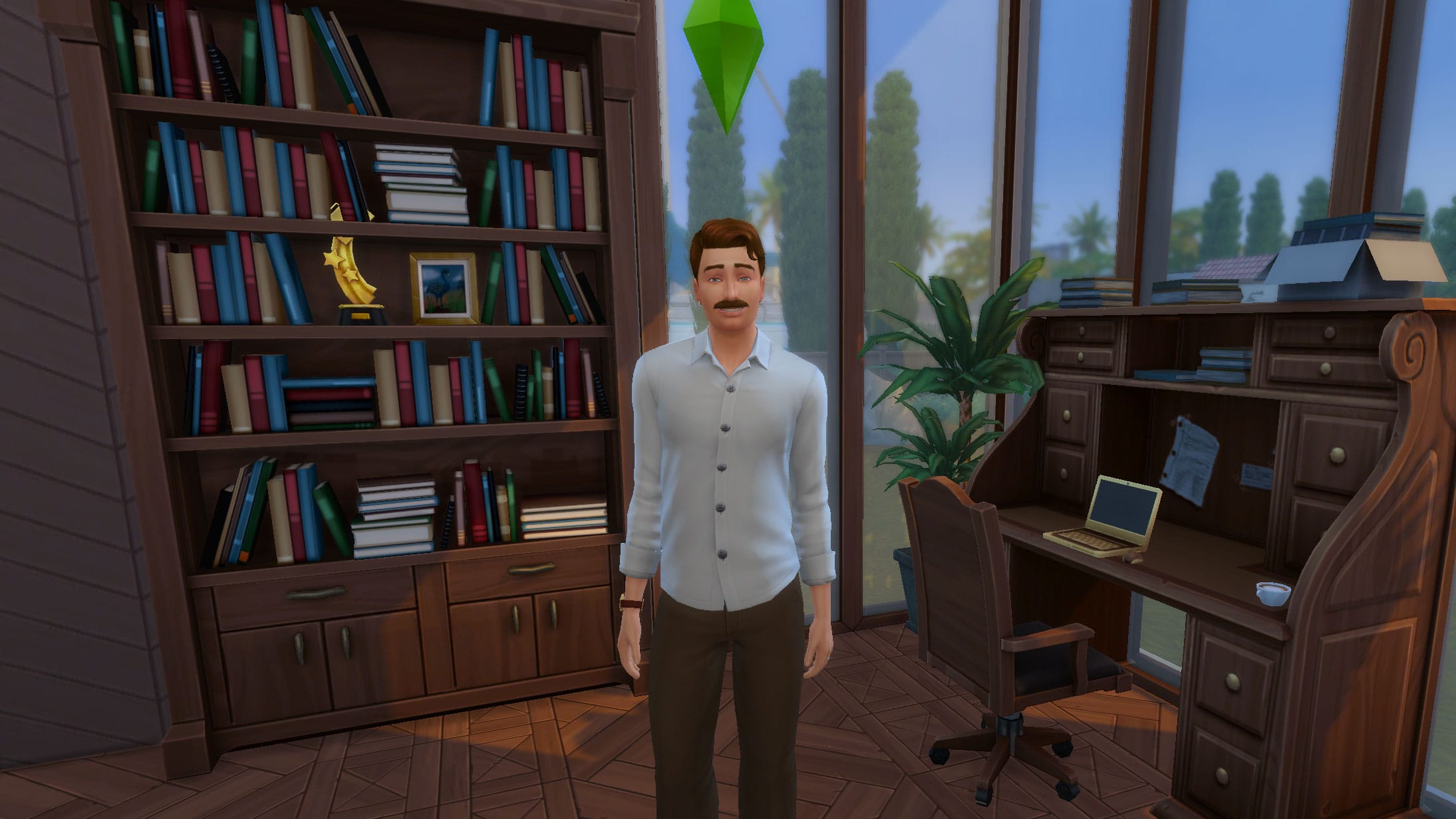

In recent years I have played the Sims 4 in different stints. When I first downloaded it, I made an updated version of my dream home. There was no empty space. Wood. Not the kind that splinters and stains. Sustainably sourced, of course. Beams in the ceilings with hanging plants. My mother’s ornaments stacked upon them. There were shelves of herbs and baking ingredients. There was a room for my Sim to sit and type his novels with abandon. Behind him, there’s a huge bookshelf. The books my mother gifted me. Wall-sized windows that let the light in. Rooms decorated with memories. Faces in photographs fill the rooms with love.

Beyond the double-glazed doors that swoop open, there is a patio where you can sit and read in the summertime. Beyond that, a stretch of grass. There is a wardrobe of shirts. An award for my Sim for his writing. A cataclysm inside me, that all of this might be possible one day. From homeless to home owner.

Recently, EA decided to sell the rights for the Sims franchise. However you feel about this decision, it is a stark reminder of capitalism in a game that allows you to imagine a life beyond your limits. Sometimes I come home from a writing event and check the time. Should go to bed, but there’s an hour free. I think about opening the game sometimes, but I feel less of a pull to build a fantasy like this based in a speculative future. In my neighbourhood now, I pass houses with their low orange lights on, wonder what it feels like. Stare longingly into shadows in the doorways and listen out for the laughter, wondering exactly how it would feel to have something to call my own. That stained-glass window. That perfect desk I can see refracting the light. Pick pieces apart from them and compare it to the place I’m living.

Perhaps, even though I am not playing it out in The Sims, I am still in this state of longing. Maybe it’s a feeling of finding a place to settle. Maybe it’s piecing together a life that’s intentional. I know this kind of play was integral to me becoming a writer. In The Sims, I realise, too, I was not just building my dream house; I was building my own identity. Lately, when I’ve been asked where I grew up, I generally say Yorkshire, since it’s the most fitting description of my sense of place. But home, to me, has become more than this. It is the people you know. The work you do. The stories. The people you love. The friends you keep. The healing you work through.

Because a home, even for a Sim, is more than a house.

1. Housing And Young People, A Complicated Relationship: Children In Temporary Accommodation

2. Sims currency

3. For further consideration of the relationship between therapy and online environments, see Drama Therapy in Virtual Reality: A Study on SessionDesign and Empathy Improvement by Yoriko Matsuda, Yutaro Hirao1, Monica Perusquía-Hernández, Hideaki Uchiyama and Kiyoshi Kiyokawa, Nara Institute of Science and Technology, 8916-5, Takayama, Ikoma, Nara 630-0192, Japan

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments