In the late 1930s, prompted by her increasing unease at class divisions in Britain, the rise of the Brownshirts, and those who had “left village life and all it stood for behind them”, Flora Thompson, who ran a provincial English post office, began to explore the prospect of writing her childhood memoirs. She felt part of a class that had been forced to “choose between merging themselves in the mass standardisation of a new civilisation” and “adapting the best of the new to their own needs while still retaining those qualities and customs which have given country life its distinctive character”. Stanley Baldwin’s 1927 speech, What England Means to Me, epitomised a growing national nostalgia for “the last load at night of hay being drawn down a lane as the twilight comes on, and […] that wood smoke that our ancestors, tens of thousands of years ago, must have caught on the air when they were still nomads”

Meanwhile, writers such as Stella Gibbons were parodying the peculiarities of rural life with Cold Comfort Farm at the same time as Mary Webb and her Shropshire romances sold like the hot cakes their protagonists were endlessly baking. The repeal of the Agricultural Act in 1921 slashed the minimum wage for farm labourers, with arable farms arguably the worst hit. As a result, working-class country people were forced to migrate beyond the villages in which their families may well have spent generations, looking for work. This cultural moment was reflected in the literature of the time; Alice Spawls, reviewing Richard Mabey’s biography of Flora Thompson in the London Review of Books in 2015, observes: “Forster wrote a pageant in praise of the Surrey village of Abinger; Ravilious, Nash and Piper created iconic images of cornfields, cliffs, country houses, hay bales and ploughs. HV Morton’s record of his journey around the countryside in a Bullnose Morris, In Search of England, was a bestseller (30 editions in less than six years). He wasn’t alone in being more concerned with the country as metaphor than as fact.”

Similarly, in the US, Laura Ingalls Wilder had in 1935 published Little House on the Prairie, her bestselling children’s series which sanitises the dark history of settler expansion in the American Midwest during the late 19th century.

Thompson’s drive to compose what would become the Lark Rise to Candleford trilogy may have been a response to the pastoral genre’s popularity and market boom in the early 20th century. She was also a political writer, however. That she writes about the Lark Rise families’ poverty, and the tensions of party-political allegiances in the hamlet, is well known, even if these subjects tend to be downplayed in adaptations. But it is less remembered that she tackles inequality, post-enclosure oppression and class solidarity with a sharper edge than she tends to be credited with. In a passage about the harvest celebrations, she undercuts the bucolic scene by noting that the “joy and pleasure of the labourers in their task well done was pathetic, considering their very small share in the gain”. Later, when describing the celebratory feast, she goes further: “the farmer paid his men starvation wages all the year and though he made it up to them by giving that one good meal. The farmer did not think so, because he did not think at all, and the men did not think either on that day; they were too busy enjoying the food and the fun.”

If the difference between working-class writing, and writing about the working class, is the class-consciousness of the author, then Thompson certainly qualifies as the former. She clearly shows a class solidarity in operation at work – one that cuts across age and gender. “A new field had been thrown open for gleaning... Bob Trevor had been on the horse rake when the field was cleared and had taken good care to leave plenty of good ears behind for the gleaners. ‘If the foreman should come nosing round, he’s going to tell him that the rake’s got a bit out of order and won’t clear the stubble proper. But that corner under the two hedges is for his mother.’”

With characters like Queenie, Thompson evokes a recent, pre-enclosure past when people enjoyed freedom, access to land and a life in which work and pleasure were not cleanly separated. By contrast, in the present they are wage earners only, keeping their families on starvation wages of 10 shillings a week. She depicts bourgeois, urban ignorance of the injustice in the form of the interlopers from towns who exclaim over the cottages of rural working-class people, wondering how “they brought up ten children there! Where on earth did they sleep?” (For Thompson, of course, the answer was obvious: not all at the same time.)

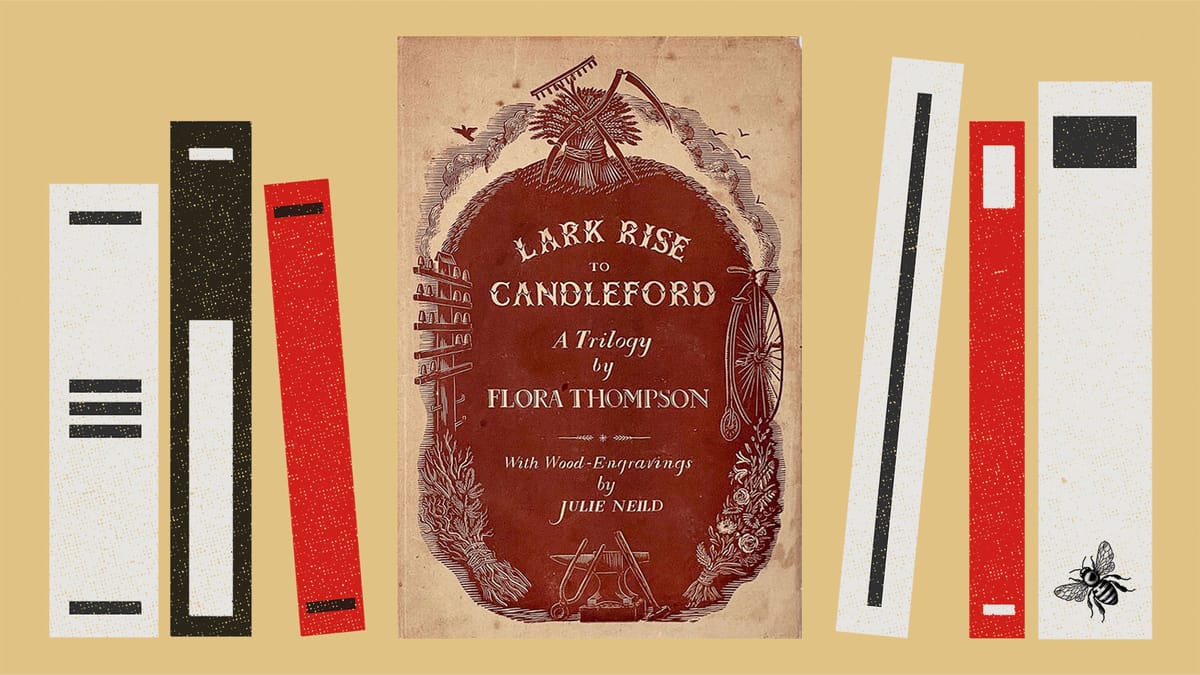

Thompson’s trilogy appears to have been positioned by OUP to appeal to middle-class, Victorian-esque sensibilities and a notion of the English countryside as a soft and gentle place. Consequently, her class consciousness has rarely been much present in the presentation of the book, whether that be the received pronunciation of the narrator in audio, the permanent golden-hour light and soap opera-esque characterisation in the BBC TV adaptation, or the cover designs of print editions. The Oxford University Press’s original slim standalone volumes are simply designed clothbounds, featuring elegant art deco bevels and foil lettering. By contrast, the first trilogy republication takes on a significantly more baroque look, with Victorian pastoral imagery littering the dustcover front: haymaking, corn sheaves, blacksmithing and penny-farthings abound.

Prominently advertised on the cover are Julie Neild’s original wood engravings, which appear as chapter headings within. It is striking to revisit this text, and especially its opening chapter – “Poor People’s Houses” – in the context of class. Despite Mabey’s attempts to reclaim her, Thompson is not primarily remembered as a nature writer from her era; it is all reminiscent of the treatment of John Clare, the lauded working-class Romantic poet famed for his descriptions of the English Midlands countryside, whose name is frequently excised from certain canons in favour of the middle- to upper-class Keats, Shelley, Byron and associates.

Subsequent Lark Rise to Candleford covers retained the quaint botanical feel of the first trilogy, from the 1954 OUP reissue to the 1973 Penguin Classics paperback, the 1979 Book Club Associates hardback, the 1984 Penguin Modern Classics paperback, the 1986 Century clothbound, the 2008 PBS and BBC adaptation tie-ins, the 2020 Macmillan Collector’s Library edition, and the 2021 Oxford World’s Classics paperback. The latest Slightly Foxed series cloth hardback from 2022 is a striking departure, featuring the series standard blank teal front, coloured endpapers, silk ribbon and spine gold blocking.

Thompson’s archive in the University of Exeter’s special collections includes her correspondence with her friend Mrs Tylor, and the main subject of their letters is their reading, and they often discuss lending each other books. The books Thompson mentions reading or wanting to read appear to be predominantly by women, including Emily Carr, Gertrude Bell, Winifred Holtby, Vera Brittain, Fanny Burney, Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell. It is striking that Tylor and Thompson were clearly reading and discussing the works of radical women writers similarly working within the pastoral tradition. (I was quite delighted on doing some further digging in the collections’ index to discover that in one letter, Thompson specifically mentions her love of “betting on horse racing”.)

She remained adamant throughout her life that Lark Rise to Candleford was produced first and foremost as fiction and should be read as such. In her letters, the feeling becomes stronger as she gets older. Considering this in the light of her reading and her politics as expressed in Lark Rise to Candleford, you wonder if there was a frustration that she had wanted to present a world, and instead was allowed only an opinion. It is true, as Mabey says, that she lacked sufficient “skills of empathy and character development and plot construction necessary for a sustained work of fiction”. Lark Rise to Candleford, particularly in its first part, lacks a real protagonist; you might argue that she tries to make the hamlet, or the class, play that role. Nevertheless, it is impossible not to feel some sympathy with her feeling of somehow being sold short. Some of us may wonder how differently this conversation might have gone if Thompson had been perceived to be middle- or upper-class by her publishers.

*

Flora Thompson, née Flora Jane Timms, was born on 5 December 1876 (although this date is disputed by some sources as 1877) in Juniper Hill, Oxfordshire. She was the eldest of six children born to Albert, a stonemason, and Emma, a nursemaid. Thompson’s favourite brother, Edwin – the fictional “Edmund” in Lark Rise – was killed near Ypres in 1916; her sister Betty also became a successful author with her 1926 children’s book The Little Grey Men of the Moor.

The Timms household was a challenging one, plagued by poverty and the effects of her father’s alcoholism. He had been a talented stone carver involved in the restoration of Bath Abbey, but the financial pressures of marriage and family life put a stop to his professional ambitions. A lifelong socialist and agnostic, Albert Timms was also a social outcast in the rural community to which the family belonged. Thompson’s mother, by contrast, was a creative spirit who encouraged her children to make up stories and taught them to read by the time they started school. As Thompson herself remembered: “My brother and I used to make up verse and write stories and diaries from our earliest years […] No one saw them; there was no one likely to be interested.”

Unlike most of her schoolmates, who left school at 12 to take up work in the fields or in service (the Elementary Education Act 1880 mandated education only up to the age of 10), Thompson left school at 14 to work as a post office clerk in Fringford. During this time, she remained a keen observer of parish affairs, and would later conjure these scenes for her novels, including “the naughty children who pulled her hair, Queenie who spoke to bees, the annual pig killing, May Day, the harvest”. (“Even decades after leaving the village it seemed she could recall a life long left behind, the geraniums on the windowsill, the cottage smell of ‘apple and onion and dried thyme and sage ... a dash of soapsuds’, even the way the pig-sticker fastened a piece of the animal’s fat over its foreleg as it hung to drain, ‘in the manner in which ladies of that day sometimes carried a white lacy shawl’.”) Indeed, Thompson had no shortage of books with which to nourish her love of literature; her local Mechanics’ Institute library supplied her with British classics including Jane Austen and Charles Dickens.

During this time Thompson lived with her mother’s cousin, Kezia Whitton, who owned her own post office and introduced Thompson to a grander quality of life than she had been used to at home, with two eggs for tea and “canary dip” baths (a few inches of warm water scented with eau de cologne).

Thompson’s years in Fringford would later inform the third Lark Rise volume, Candleford Green, which partially documents the shifting social boundaries of the turn of the century. The “newly built villas” were soon filled by, as she would write, “journalists, army pensioners, Nonconformists, progressive aristocrats and middle-class families”. Although Whitton planned to bequeath Thompson the post office, at the age of 22 she decided to transfer instead to another post office in Grayshott, Hampshire.

Grayshott was home to the Hilltop set, which included such literary giants as Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw and Christina Rossetti. Thompson felt out of place in this environment, hoping at once to be noticed by “the Hilltoppers” and also to remain invisible and undisturbed. She also attended political rallies and speeches. In one alarming incident, her landlady Mrs Chapman was murdered by her husband while Thompson was, it appears, present in the house; Thompson recorded only that “Women [were] running into their houses and locking their doors when they heard a madman was at large ... then the arrival of the closed carriage ... and the dazed culprit ushered into it, arm in arm with doctor and policeman, while all the time, but a few yards away, the sun shone on the heather, pine-tops swayed in the breeze, birds sang and bees gathered honey, as on any ordinary summer morning.”

Thompson found her future husband in a fellow clerk, John Thompson. They married in 1903, and their daughter Winifred was born the same year, followed by a son, Henry (sometimes known by his middle name, Basil) in 1909. Thompson left the postal service to care for her children at home after her marriage. Her husband has sometimes been characterised as a disapproving presence who discouraged Thompson from her writing endeavours, but nonetheless she continued to write, winning a literary essay contest in The Ladies Companion magazine in 1911 for a 300-word piece on Jane Austen. A year later, the magazine published her first short story, The Toft Cup. The same year, she won a Literary Monthly competition for her response to Ronald Macfie’s poem about the Titanic. Macfie became a mentor to Thompson; they corresponded all his life, but after his death the first president of the Poetry Society, Margaret Sackville, saw “no point in keeping such rubbish” and burned their surviving letters.

In 1918, Thompson gave birth to her third and final child, a son named Peter. Not long afterwards, in 1921, she began penning the Out of Doors column for The Catholic Fireside. Philip Allan & Co also published her collection of verse, Bog-Myrtle and Peat, that year. By this time, Thompson was a wife and mother in her mid-40s, living in a terraced house in Liphook and embarking on 20-mile daily walks up into the nearby pines. To her readers, she characterised herself as an unmarried middle-class woman living a country life alone amongst her “books and pictures, the old writing table at which my father wrote out his prescriptions, my grandmother’s blue and white china, and the samplers of my great aunts”. As Alice Spawls writes in the London Review of Books, “the ‘good life’ that she created in the column was not that of a famous writer, nor of a housewife or rural villager, but of a comfortable single woman who wrote in order to live as she pleased”. The column was subsequently renamed the Peverel Papers when the fictionalised Thompson decided to move to a cottage beside the Peverel Downs in the New Forest. It is striking that the unreligious Thompson wrote fervently until 1927 for The Catholic Fireside, which had originated as a monthly penny magazine directed primarily at working-class Irish Catholics in Britain.

As the second world war inched closer, and by then well into her 60s, Thompson sent some 15 chapters of her childhood memoirs to Oxford University Press. These would become the spectacularly successful memoirs Lark Rise (1939), Over to Candleford (1941), and Candleford Green (1943). The prodigiousness of Thompson’s writing in this vein meant that the books could be republished as a cohesive trilogy in 1945, almost as soon as the third had come out. That trilogy was titled Lark Rise to Candleford.

Thompson was not able to enjoy her sudden literary celebrity, however. The books became bestsellers for OUP, but Thompson herself felt she was “too old to care much for the bubble reputation […] Twenty years ago I should have been beside myself with joy”. Shortly after Thompson and her husband retired to Brixham in Devon, her 22-year-old son Peter was killed when his ship was torpedoed in 1940. By all accounts, Thompson never recovered and died of a heart attack seven years later, on 21 May 1947. At the time of her death, she had been working on an unfinished novel about a retired teacher, Charity Finch, titled Dashpers. Her memoirs Still Glides the Stream and Heatherley were published posthumously by OUP in 1948 and 1979 respectively.

*

The Lark Rise books were positively reviewed from the off: an early review praised their rendering of “the separation that lies between the state of happiness and what is known as progress”. In his 1957 introduction to the trilogy reissue, H J Massingham wrote:

By the playing of these soft pipes the hamlet, the village and the small market town are reawakened at the very moment when the rich, glowing life and culture of an immemorial design for living was passing from them, at the precise point of meeting when the beginnings of what was to be touched the last lingering evidences of what was departing […] A triumph of evocation in the resurrecting of an age that, being transitional, was the most difficult to catch as it flew; another in diversity of rural portraiture engagingly blended with autobiography; and the last in the overtones and implications of a set of values which is the author’s “message”.

There is, however, an argument that the books are of their time. Thompson’s prose is simplistically structured, with a transparency of phrase and descriptive power reminiscent of George Orwell’s advocacy of prose “like a window pane”, in which the lightest-touch narration falls away and the reader is fully immersed. Spawls gestures towards Thompson’s tendency to “soften […] the darker realities” of rural life, noting that “Death (half of Thompson’s siblings died before adulthood), drinking, destitution, violence: all are treated lightly, if at all […] In part, Lark Rise has no real plot; her best writing was recounting. Her powers of observation, so finely attuned to the natural world, could not get beyond the surface of the people around her […] If Thompson was guilty of disingenuousness – the most common criticism levelled at her – subsequent editions and interpretations (especially the cakes-and-ale BBC adaptation) have done little to right this, portraying her Oxfordshire village as the last bastion of a harmonious way of life threatened by modernisation from without, rather than by poverty and cruelty within.”

The modern reception of Thompson’s work as a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman set in a rural farming community sheds some light on Mabey’s perplexity that, despite the trilogy’s popularity, “the web of authorial legend and topographical curiosity that builds up around nationally popular texts simply hasn’t gathered around Lark Rise”. Indeed, Thompson’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography plays into this nostalgic sentimentality, lamenting that “few works better or more elegantly capture the decay of Victorian agrarian England”. One passage in particular stands out as an example of realist reportage of contemporary working-class rural life:

“There must have been hundreds of tramps on the roads at that time. It was a common sight, when out for a walk, to see a dirty, unshaven man, his rags topped with a battered bowler, lighting a fire of sticks by the roadside to boil his tea-can. Sometimes he would have a poor bedraggled woman with him and she would be lighting the fire while he lolled at ease on the turf or picked out the best pieces from the bag of food they had collected at their last place of call […] Where all these wayfarers came from or how they had fallen so low in the social scale was uncertain. According to their own account, they had been ordinary decent working people with homes “just such another as yourn, mum”; but their houses had been burned down or flooded, or they had fallen out of work, or spent a long time in hospital and had never been able to start again. […]

“Laura’s father, coming home from work at dusk one night, thought he heard a rustling in the ditch by the roadside. When he looked down into it, a row of white faces looked up at him, belonging to a mother, a father, and three or four children. He said that in the half-light only their faces were visible and that they looked like a set of silver coins, ranging from a florin to a threepenny bit. Though late in the summer, the night was not cold. “Thank God for that!” said the children’s mother when she heard about them, for had it been cold, he might have brought them all home with him. He had brought home tramps before and had them sit at table with the family, to his wife’s disgust, for he had what she considered peculiar ideas on hospitality and the brotherhood of man.”

The spatial arrangement of Laura’s father literally “looking down” upon the itinerant family in this section extends a striking metaphor to the way in which the trilogy was published – a kind of rural, mid-20th-century version of poverty porn.

*

Despite Mabey and others’ suggestions that Lark Rise to Candleford – and Thompson’s work more broadly – now sits in a neglected corner of literature, the trilogy has apparently never been out of print. It is intriguing that the books have largely been sold and marketed as a single-volume edition since they were originally combined in 1945. Was this decision in some way responsible for the novel’s breakout success, when the original three volumes might otherwise have slipped below the noise of pastoral novels in the first half of the 20th century?

It appears that this move may have been more economic than editorial, given that it occurred during the Paper Salvage campaign, which attempted to mediate the national wartime paper shortage by encouraging the recycling of paper waste.

Lark Rise may have had the effect that it did on British ruralist writing because of some happily serendipitous timing; after all, Thompson had been writing in a similar vein for some years by the time of its publication. She was likely unable to commit to more intensive novel-writing earlier while her children were young, but by the late 1930s, when she approached OUP with those first 15 chapters, her youngest child was in his late teens. Equally, in the period immediately preceding and following the war, “the myth of Rural England as the wellspring of national greatness”, as Phillip Mallett writes, was grasped at with increasing urgency by cultural productions.

Lark Rise to Candleford belongs to a rich tradition of English memoirs, essays and journals about the countryside. This is a tradition in which one can detect two impulses, at variance with each other but often to be found side by side. One is ostensibly historical, or documentary. Its ambition is to report on the condition of rural England […] The other is imaginary, or mythical, though it rarely confesses itself so. It invests equally in the countryside as the home of virtue and independence, typically in contrast with the corruption of the city, and in the restorative power of landscape itself. It conjures an ideal England, sometimes envisaged as a project for the future, but more often found in an earlier Golden Age, when people lived in rhythm with the land and the seasons. Lark Rise to Candleford can be and has been recruited for both aspects of this tradition, as an authentic record of a way of life which in the 1880s stood on the brink of modernity, already vanishing and now vanished, and as an example of the nostalgic strain in ruralist writing, which harks back to a time when men and women were happier, and perhaps better.

In his biography of Flora Thompson, Dreams of the Good Life, Mabey notes how her rural classic “rises like Excalibur” to the tune of national crisis. Its adaptation to the National Theatre stage first appeared during the winter of discontent between 1978 and 79, while 1983’s illustrated edition sold a million copies at a time of high unemployment and industrial conflict, and the BBC TV series was broadcast in 2008 at the peak of the financial crash. A two-part radio adaptation for BBC Radio 4 was also released as Lark Rise to Ambridge in 2023 while energy prices soared and the “cost of living crisis” set in. It is difficult to put forward any singular explanation for this strange pattern without surfacing the recursive causation/correlation debate, but as Agnes Arnold-Forster puts forward in Nostalgia: The History of a Dangerous Emotion, “Expressions of nostalgia are one way we communicate a desire for the past, dissatisfaction about the present, and our visions for the future”.

As Thomas Waters puts it: “Since Thompson’s death in 1947, [Lark Rise to Candleford] has come to be considered as a – indeed, perhaps the – classic account of life in the late Victorian countryside. That much, at least, is suggested by its popularity, which exceeds that of the other esteemed works of rural history and literature, such as Joseph Ashby of Tysoe, The Wheelwright’s Shop, Kilvert’s Diary, and even Laurie Lee’s Cider With Rosie.” The statement indicates the extent to which history has largely sanitised the portraits of poverty and hardship in Thompson’s work, as well as its frequent foregrounding of social class. After all, she herself was hardly an “esteemed” writer for most of her adult life, having navigated an uneasy line between her working-class upbringing and later co-option into the emerging demographic of the lower-middle class in the South Midlands with varying success, sometimes costuming herself in the guise of the middle class to further her writing’s appeal, as in The Peverel Papers.

In her preface to the 2022 Slightly Foxed edition, Nicola Chester writes: “In her mind Flora never left Lark Rise entirely – and nor have I. We seem always to be walking away, distracted by the wayside flowers, but casting lingering last looks over our shoulders even as we move inexorably forwards.” She laments the ravage of urban change on rural life today, which feels an ironic point of comparison given that Lark Rise is itself not a stable category of rural bliss.

What strikes me is that this text carries so many hallmarks of being a “woman’s” book: its female protagonists are often spirited and vividly drawn, unlike certain other giants of the pastoral genre such as Thomas Hardy’s Tess. Chester quotes Thompson’s own wistful idea “had she lived later she must have made her mark in the world, for she had the quick, unerring grasp of a situation […] but there were few openings for women in those days, especially for those born in small country villages”.

Indeed, Lark Rise to Candleford affords a meaningful window into the lives of rural working-class women in England during the late nineteenth century via “a fascinating system of respectful borrowing (a spoonful of tea or the heel of a loaf to tide a household over until pay day, when it would be repaid) and the appearance of ‘The Box’, containing a baby’s layette that was shared around after each new birth”. “The women wished above all things to be on good terms with their neighbours.”

The BBC TV adaptation, which ran from 2008-2011, reflected this representation of women. It was also similarly nostalgic and starred a number of well-known comedy actors including Dawn French and Mark Heap, which cemented its reception as a “lightweight” drama. Its TV slot at 8pm on Mondays also followed the very popular Downton Abbey’s primetime Sunday night on ITV, which dealt similarly (and largely toothlessly) with entanglements of class tensions in rural England around the turn of the twentieth century. The BBC adaptation of Lark Rise also played up the middle-class overtones, with decadent costumes and set designs as well as increasingly outlandish storylines such as the Christmas ghost story which opened Season Two in 2008-9.

Audio editions of Thompson’s work dominated by middle and upper-class voices, not least the Karen Cass-narrated edition released in 2019 and available on Spotify. Cass is an acclaimed voice actor with a strong RP southern accent. The old Oxfordshire regional accent which would have belonged to Thompson, by contrast, has been compared to a modern-day West Country accent by native speakers. Voice experts for the BBC add that “Oxfordians don’t open their mouth as much as other places. That makes our pronunciation different. I would say ‘kid-lit-en’ instead of Kidlington”; “Our local Oxford delivery was much slower, and I found myself at a disadvantage at first with much quicker speaking Surrey or London folks”; “When I went to University, people often mistook my Oxfordshire accent, with its drawn out a’s, with a west country accent […] Certainly, the older generation still refer to youngsters as ‘My duck’ (pronounced durrck)”. Perhaps the “original” Oxfordshire accent which would have permeated Thompson’s work is rapidly dwindling out of existence, and has become less associated with the Oxfordshire of Lark Rise to Candleford than th RP you might more commonly find there today.

Likewise, there is a class-washing factor to this evolution. In a BBC Inside Out feature on accents, members of the West Country public decried the derogative “local yokel” stereotype that has become attached to this particular accent. “If you were to speak like Vicky Pollard [a West Country, working-class satirical alter ego created by the public-school educated comedian Matt Lucas], you’d be classed dumb, lower-class and not very intelligent,” as one person said.

Thompson’s own accent remains something of a point of contention. Mabey puzzles over the fact that no one truly knows whether she was still speaking with a rural Oxfordshire accent at the end of her life. He draws a comparison with her contemporary JB Priestley, who featured regularly on wartime radio, and wonders why Thompson was never similarly recorded. As Kathryn Hughes writes in her review of Mabey’s biography, “it suited everyone to think of Thompson not as a journeyman writer but rather as a hedge-scribe, an empty vessel through which the rural England of the 1880s had channelled its dying song. To drag Thompson from behind the counter of the village post office, where she was fondly believed to have spent her adult life, and put her on air would be to spoil the myth of Lark Rise […] While the middle-class folk revival that ran parallel with her own childhood in the 1880s had been all about retrieving an ageless Arcadia, she was more interested in mapping rural England’s undoing.”

Hughes adds that Lark Rise to Candleford’s “generic instability” as it hovers between fact and fiction may be at the root of its lack of critical acclaim, painting Thompson as “a class traitor who peddled sloppy rural fairytales for wistful suburban readers”. While Lark Rise to Candleford has certainly achieved cult classic popular status, its literary prowess is less certain. Hughes claims that “If it were published today, we would have no problem with its inbetweeness”, but the publishing industry has always enforced commercial boundaries to an extent, and boundaries between genres and class and much more. Hughes ends by writing, poignantly, that at its heart, “Lark Rise is a fable that can be constantly reworked to suit the changing moment. That is why you can read it as a celebration or condemnation of technology, a love song to old hierarchies or a cry to knock them down, a blissful acknowledgement of the community’s nurturing nature, or a sharp kick against its confining walls”.

The trilogy was adapted for the stage again by Keith Dewhurst in 2005 at the Finborough Theatre in West Brompton, a Time Out Critics’ Choice “two play adaptation” which, interestingly, “can be seen in any order, separately or together”. According to the website, Dewhurst “creatively reinvents the tiny Finborough theatre as the highways, outhouses and smoky taverns of Flora Thompson’s Oxfordshire hamlet, bringing every aspect of this lost lifestyle to the stage, from the midwinter fox hunt to the midsummer harvest, from climbing trees to throwing snowballs[,] connecting with our continuing struggle for a national identity”. Perhaps we are due another adaptation of Lark Rise to Candleford in 2026.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments