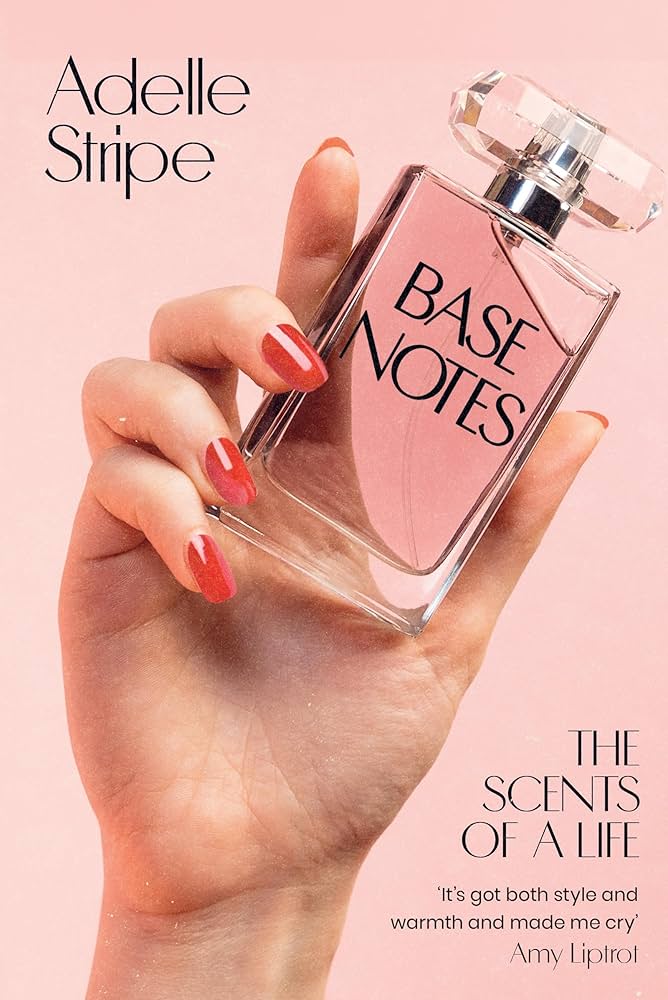

The critically acclaimed Adelle Stripe excels in taking people, places and experiences that don’t quite fit into the run-of-the-mill way of things, and creating ways of writing about them that feel true. With Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, she helped us to reappreciate the work of the Bradford playwright Andrea Dunbar; with Ten Thousand Apologies: Fat White Family and the Miracle of Failure, she took one of the UK’s most controversial bands and span entire cultural histories. Base Notes: The Scents of a Life, her 2025 memoir, is a grittily lyrical and bleakly comic story of growing up in and getting away from a northern brewery town in the late 20th century. It is also possibly the only memoir of its kind with chapters themed around remembered commercial fragrances. On the eve of Base Notes’ publication in paperback, The Bee met up with her in Scarborough’s famous Harbour Bar cafe to talk about childhood, books and the experience of becoming a working-class writer.

To begin with, though, she requested a very specific kind of question. Always happy to indulge a writer, we were glad to oblige…

Richard Benson: So, Adelle, Base Notes has been acclaimed since it was published last year. Looking back, you must feel pleased?

Adelle Stripe: Yes but I was wondering if you could ask me a different kind of question?

RB: How do you mean? What kind?

AS: Like Smash Hits questions. Like, does your mother play golf, or what’s your favourite crisp?

RB: I’m supposed to ask about Base Notes.

AS: Well, we can do that in a bit. Go on, ask me about crisps.

RB: Right. What’s your favourite crisp?

AS: Seabrooks. I used to be a fan of the smoky bacon ones, but you don’t really see them any more, so I default to Worcester Sauce. I’m not a massive crisp fan, actually.

RB: I assume you are a fan of ice cream, as you suggested we meet here in the Harbour Bar in Scarborough. What would your preferred flavour be?

AS: Coffee, but you can’t find coffee ice cream in many places any more. It’s a 70s or 80s retro flavour, and rare, sadly. Sometimes you’ll find a cappuccino flavour. I’m a big fan of Brymor raspberry ripple, which is off the chart, but again you can’t find raspberry ripple either.

RB: Least favourite?

AS: Well, I don’t like salted caramel as a flavour, which is unfortunate as it’s ubiquitous. It’s almost the raspberry ripple of the 21st century.

RB: Have you ever punched someone?

AS: Over ice cream?

RB: No, in general. It’s a Smash Hits-type interview question.

AS: Oh. No, I’ve never punched anyone, but I did bite a girl’s face. I was getting picked on by this girl, and my mum said, “whatever they do to you do back to them twice as hard.” So one day at school, she bit my arm, and we ended up fighting and I bit her face. She had my teeth marks perfectly printed in her cheek. I was suspended from school.

RB: What item do you most commonly lose?

AS: My glasses. But now I’ve just invested in more spectacles, so I have glasses all over now. I managed to get a deal at Vision Express.

RB: You must wear them when you’re writing?

AS: [Pause] Are you going to make me talk about the book now?

RB: Yes. I’d like to ask how it came about. It’s a coming-of-age memoir that deals with your relationship with your mum, and your youthful experiences in her hairdressing salon. How did you get started?

AS: I’ve been writing it for 20 years. Some of the stories are really old, but I didn’t want to put them out as my first book, because I wanted to write other stories first. I was conscious of being defined by writing a memoir as my first book. I mean, there’s an argument that all writers’ first books are memoirs, even if they’re novels; they’re all thinly disguised romans à clef. I kind of knew that, so I thought, that’s why I’m going to write Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile [Stripe’s first book, a fictionalised biography of the life of Andrea Dunbar that was published in 2017 by Wrecking Ball Press and then republished last year by Virago.]

RB: So, what was the catalyst that made you do it?

AS: I had this idea that I wanted to write about the hairdressing salon, and I had these little fragments. I had a few sentences here and there, and I just really took myself back to being a girl in the salon, sitting in the waiting area, looking through the glossy magazines and smelling the scented strips inside the magazines. Looking at those perfume adverts took me to places. I would smell the Giorgio Beverly Hills or the Poison or the Opium; I would rub them on my wrist, and I would look at the images. And that was quite exciting to me, because Tadcaster, where I lived, was so fucking boring and dull. I mean, it was just not a very inspiring place to live when you were a kid, style-wise.

In Base Notes I’ve written this sort of mock advertising copy at the beginning of every chapter because I wanted to reimagine what that effort looked like and where it took me, and I wanted to think about perfume copywriting, which is a funny thing, style-wise.

RB: Base Notes’ chapters are titled with the names and descriptions of perfumes, which is interesting for a memoir because smell and memory are strongly connected. Did thinking about the smells trigger particular recollections?

AS: Yes. Just when I thought about the perfumes, not only did I remember the smell of them, but I could also remember all these details attached to that smell, like where I was at the time, and what people were wearing. The actual fragrances triggered deeper memories.

I started doing some writing around smell and memory. It was very formal and journalistic, and I wrote a feature on each fragrance that I remembered. I researched the history, all of the different elements in the fragrance, why they were like they were – doing deep journalism into each one of these fragrances. At that point I thought it might just be a non-fiction book about perfume that I was writing. And then I started pulling in these memoir sections, and what I realised was that the memoir was more interesting than the journalism, which anybody could have written. So I just cut all the journalism out and dumped it, because it wasn’t doing anything unique. Then it became a different book altogether.

RB: Did writing the book change how you felt about your mum?

AS: I think so. My mum died in 2015, and we’d always had a really tricky relationship. But I felt that by writing the book, I came closer to her, more accepting of her. I sort of realised what a special person she was, and I felt like I understood her for the first time. I felt like I had closure and acceptance.

RB: We know from reading the book that you weren’t alike. Could you talk a bit about what she was like?

AS: Well, my mum grew up in a prefab in Withernsea in East Yorkshire. It was a harsh environment, so you see why she’d be drawn to the glamour of hairdressing. And that’s why she loved money. She loved Margaret Thatcher, because she represented aspirational working-class culture. My mum didn’t want to spend the rest of her life in a council house. She was going to have her own car, she was going to have a business, she was going to make money. And in the 1980s she got her shop, and became a capitalist. A raging capitalist. Unfortunately, just as she loved Maggie, my dad loved Arthur Scargill. So you can imagine the rows that happened in our family at home.

RB: In Base Notes, she comes over as challenging, but also very warm.

AS: She was the funniest woman. Just hilarious. And I think that’s what I really miss, that she could make me laugh, and she just had quite a twisted sense of humour. She was also a very impulsive woman, and so I think that could be quite difficult for me. She had a short fuse, and she would blow up and get very emotional. I think my personality was kind of a reaction against that, in a way, bottling my emotions up quite a lot. I don’t get angry unless I absolutely have to.

RB: Do you think there are distinct and typical problems with mother-daughter relationships?

AS: It’s so tricky, because you’re half them, aren’t you? And then if your daughter turns out not to be what you want her to be, and she rebels against you, then I think mothers feel that becoming mothers themselves is possibly the only way in which they will ever understand the pain and suffering you had to go through to bring them up. But for me, I didn’t have children. I drew the line. It was like, I’m not doing this.

RB: Did she think about you being a writer?

AS: She was actually quite supportive. I think because I was 30 when I went to uni, she was like, “Well, go do it. Yeah, you only live once.” And she was really supportive, so was my dad, like, “you only live once, and it’s clear it’s really important to you.” I’d also saved loads of money up to go to uni to get me there.

RB: Where did you grow up? Was it in Tadcaster itself?

AS: I grew up just outside Tadcaster, near a little village called Bickerton. I was there until I was four. My dad worked on a farm, and then he used to work for Sam Smith’s brewery, delivering beer on the drays, so we had a tied house. My mum didn’t work for the first few years after I was born. Well, she did a bit of mobile hairdressing, but it was mostly just me and my mum. She taught me to read and write before I went to school.

RB: Did you like to read?

AS: Yes. I was a highly advanced reader and I was voracious. My mum would take me to the library, and I read every book three times over. I remember really loving all the Roald Dahl books, The Call of the Wild by Jack London, Ursula K Le Guin’s The Wizard of Earthsea, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and even things like The Secret Garden. I liked quite a lot of Victorian children’s literature. I would read abridged versions of Little Women, books like that. My nana had Pam Ayres poetry books, and I used to read those. I like Pam Ayres.

RB: I’m assuming those are books about distant worlds, rather than reflections of you actual life at the time?

AS: Yes, I liked fantasy. It was an escape from the boredom of my life at that time. Although sometimes I liked the idea that a book was like my world, but had crazy, magic, weird stuff going on in it. Like The Secret Garden.

RB: You’ve mentioned Billy Liar as a book that captures your feelings of growing up in Tad, as they call it.

AS: Yes, Billy Liar is like The One for me. It’s a really special book, and it really does capture this idea of escape through the imagination. It fizzes with working-class energy, and Billy just … lives. He’s delusional, obviously. There’s probably a neurodivergent reading of that book to be done.

RB: You moved to east London and worked in the music industry after leaving school, then went to Goldsmiths, University of London to study creative writing when you were 30.

AS: Yes, it was wonderful. It was such a privilege to go to uni when I was 30 and not 18. I had some really good tutors there, and most of the students were working class. There were a lot of mature students, so the quality of the work was quite high. We all had life experience that we could write about.

RB: Was there a point where you became aware of being a working-class writer?

AS: I didn’t even know what being working class was until I went to university. It hadn’t really crossed my mind. But I remember reading The Uses of Literacy by Richard Hoggart and thinking, “Oh, that’s my family.” Before that I just thought my family was weird. So it was probably in my early 30s, reading Richard Hoggart. When you’re put into a university environment, it’s very middle class and academic, and you become aware of your difference. Whereas, when you’re working behind bars or working in a factory or whatever, you’re all in the same boat.

After Goldsmiths I went to Manchester University to do a master’s, and I remember in a workshop there I wrote about a guy who drank 25 pints a night. Someone in the class pulled me up on that and said, “You’re making that up. No one would drink 25 pints in a night.” I said, “No, I’m not making it up. I grew up in Tadcaster, and that’s what people do there. They’re professional drinkers.” He didn’t believe me. Someone else in the class who was from the Welsh valleys was like, “Yeah, they would drink that amount in the valleys as well.”

These disagreements aren’t necessarily about cultural disapproval. Sometimes it’s just disbelief that such differences could exist.

RB: You’ve worked in publishing and education now, as well as writing. Do you think there are factors in those worlds that can make them difficult for working-class writers to navigate?

AS: It depends on who you’re working with. I’m quite lucky. My editor at my publisher, Hachette, is from Pickering; the head of marketing is from Leeds; a lot of the sales people are from Leeds and Lancashire; the CEO is from Middlesbrough. So that’s pretty good for me, but it’s not the same with every publisher.

Publishing is painfully posh. The people who work in it are all really nice and polite, and there are lots of incredibly intelligent people who really do want things to change, but I don’t know how you bring change about while the industry is concentrated in London. Because it’s not just a class thing, it’s also a cultural thing, and the industry is so London-minded.

RB: Were there any books that gave you the confidence to write about your own life?

AS: I would say that for a lot of writers, particularly from working-class backgrounds, Gordon Burn has become a blueprint in terms of how to write non-fiction. His influence is not to be underestimated. It runs through fiction, sports writing, crime writing and journalism. If I get stuck when I’m writing, there are two writers who I turn to to help me. Gordon Burn is one, and Hilary Mantel is the other, because the clarity of her writing is unsurpassed.

RB: Can you distil what it is about each one that you admire?

AS: With her, it’s her clarity, which is unsurpassed. With Gordon, maybe it’s his ability to dig deep beneath the subject and find resonances there that other people can’t.

Another writer I’d mention is Patrick Kavanagh, and particularly The Great Hunger. When I read it, I just felt like the world of my family was there on the page, and I just felt this incredible sense of connection to the writing. That was probably one of the poems that really made me think I can do this, I can write about the world that I’ve come from. For me, it’s up there with The Waste Land.

RB: You write a lot about the north of England and its distinct culture, but you must see a marked difference between the 1980s and now?

AS: Yes, of course. Things feel bleak just at the moment. I don’t know whether it’s because I think we’re in a period of permanent decline now, and it seems that things were sliding for a long time, and now it’s just … gone. You know, we’ve seen the best of it. I know that’s really pessimistic. I try not to think about it too much.

RB: Do you think you’ll write more about your family after this?

AS: There’s one story I’d like to write, which is set in the second world war, and about one of my great-uncles. He grew up in Selby in Yorkshire, but became one of Churchill’s chief translators. He was also openly gay, and got away with it, which makes me wonder if that was because of him being in MI6. There’s quite a bit of research that needs to happen before I write about him.

RB: You seem drawn to hidden stories that are, in a way, concealed in plain sight…

AS: I think we sometimes forget that our people couldn’t write their stories down because they couldn’t read and write. We didn’t have education until the 1880s. When I go back through the census I find a lot of people who couldn’t even spell their names properly. It changes with different people – is it Strype or Stripe, for example? Family history sites on the internet are just the most wonderful resource for a writer who is interested in writing about the past or their family history, especially when that family history is an oral tradition that’s been passed down, which it usually is when you’re working class. Elizabeth McCracken said that family is the first novel. I think about that quite a lot.

Base Notes: The Scents of a Life is published by White Rabbit and is available now in paperback.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments