“You dress like a cartoon character,” people say, and I smile. Always the same colours, always the same cuts, as though consistency itself could define me. As though repetition could render me safe, accepted, and beyond their casual judgment.

“Please just stir it up a bit”, some prod.

“Can’t you afford any other clothes?” others ask.

I bat away these questions with flimsy shrugs and sighs, like I don’t want to get decision fatigue from thinking about what I wear, or I have OCD, or I just don’t care about what I’m wearing. I’m lying. Ever since I was 17, I’ve always lied about my clothing. That’s because how I dress changes the way people see me.

My uniform is heavily curated.

Comfortable, black, made-in-the-UK New Balance trainers. Classic Levi 502 jeans, slightly faded and softened from wear. A jumper, red or blue, reliably soft. Probably cashmere to serve as a gentle indulgence, preferably bought by a friend.

I know precisely what this uniform is saying.

No statement, no threat, no edge to catch your eye.

Just polished enough not to provoke judgment.

Just casual enough to blend in.

Clothing is camouflage, armour, diplomacy.

How we dress determines how we’re seen.

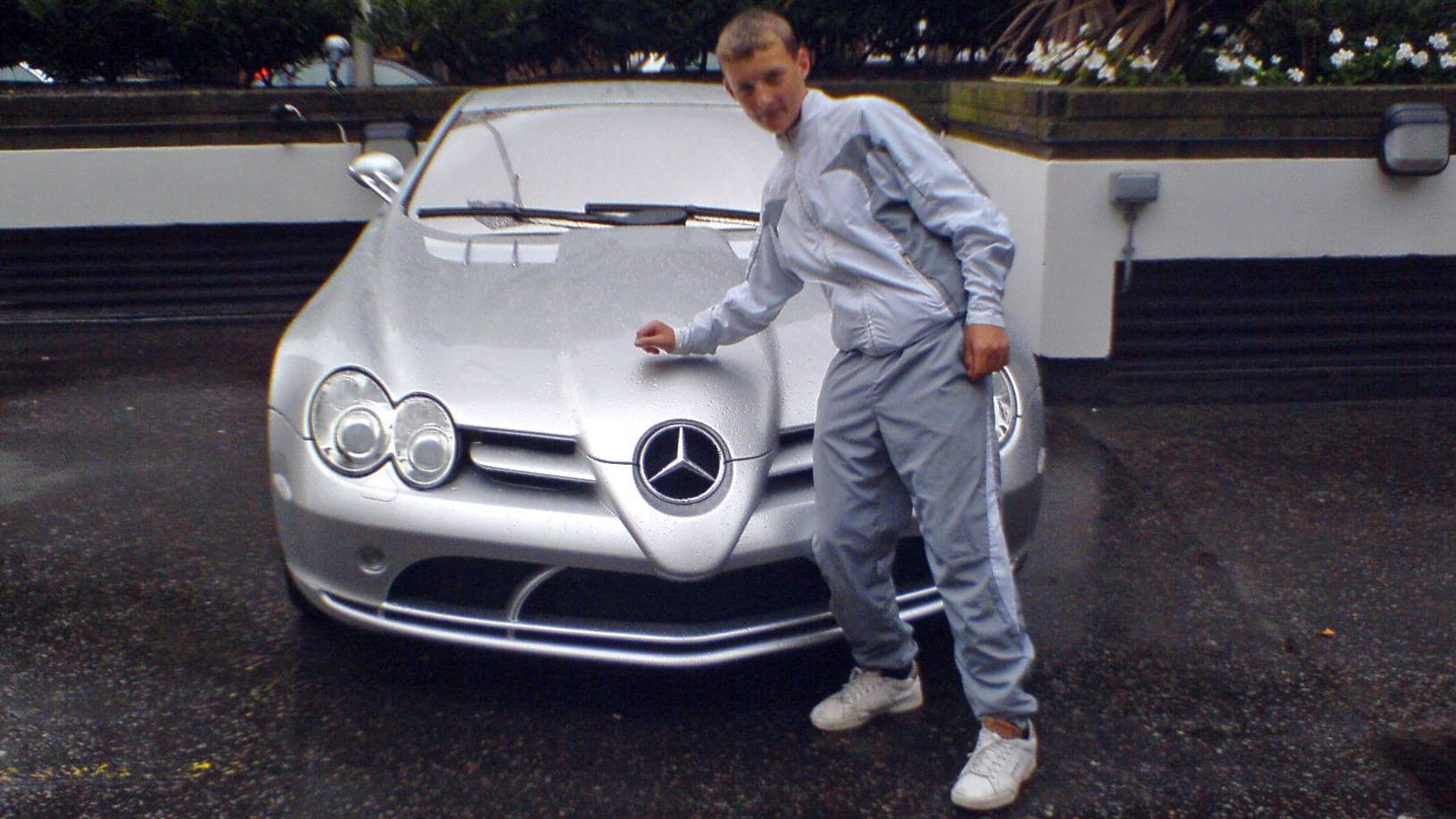

Before this uniform of blandness, I had a different outfit: the tracksuit. An arsenal of catalogued shades of rebellion.

Navy blue Fred Perry for the everyday.

Black Nike Tn for special occasions.

A grey Nike comfysuit for hazy summer days.

And a baggy blue and white Reebok tracky, loose and forgiving, dotted with hot rocks, for moments when escape came in hotboxed smoke clouds and laughter.

Tracksuits so loud they gave the entire room tinnitus.

The beauty of a tracksuit is that anyone can wear it at any time. It’s accessible to everyone.

I loved my tracksuits, and I wore them proudly and defiantly. Each zip pocket was a protest, each hood a refusal to lower my eyes, each elastic waistband holding tight the secret ache of growing up in care. But clothing can tell a louder story than any children’s-home boy could. In my tracksuit, I became shorthand: a signal, a warning sign, the butt of middle-class scorn. Middle class whispers of chav, scumbag, yob, dangerous, wrapped tight. Their assumptions gripped me as tight as the elastic cuffs around my ankles. Class has a uniform. Zipped up to the neck, with bottoms to match, pockets that zipped shut to hold the little we had safe: secrets, fists, and truths.

Now, I dress in the uniform of carefully constructed acceptance. It’s served me well.

In my work, I’ve earned respect.

But I still own some tracksuits. Whenever I slip back into them, Tesco staff follow me around the store, and the cashiers ask for ID. If I go for a run, police stop me and ask why I’m running. People avoid me. The assumptions come back. No matter how high I rise, the tracksuit returns me to my assigned class and place in society.

So, I have learned what is safe. What makes assumptions vanish. What makes doors open. What grants respect. My uniform may be heavily constructed, but not by me – by the middle-class society I live in.

Now, when I buy a coat, although it may be expensive and ‘nice’, I make sure it has zipped pockets so I can secure my secrets, my fists, my truths.

Every day, in quiet defiance beneath this bland cashmere jumper, a chav still breathes, with classic Reeboks and tracky bottoms tucked in socks, ready to run.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments