Jenny Knight has worked on farms, in pubs and factories, as an actor and a roadie, and has even renovated a former pigsty. She is now a debut novelist. Jenny is a prize-winning fiction writer whose work featured in Kit de Waal’s celebrated anthology of working-class writers, Common People, in 2019. She has worked extensively as a copywriter and editor, and taught creative writing in prisons and worked on storytelling projects in Somalia and Kenya.

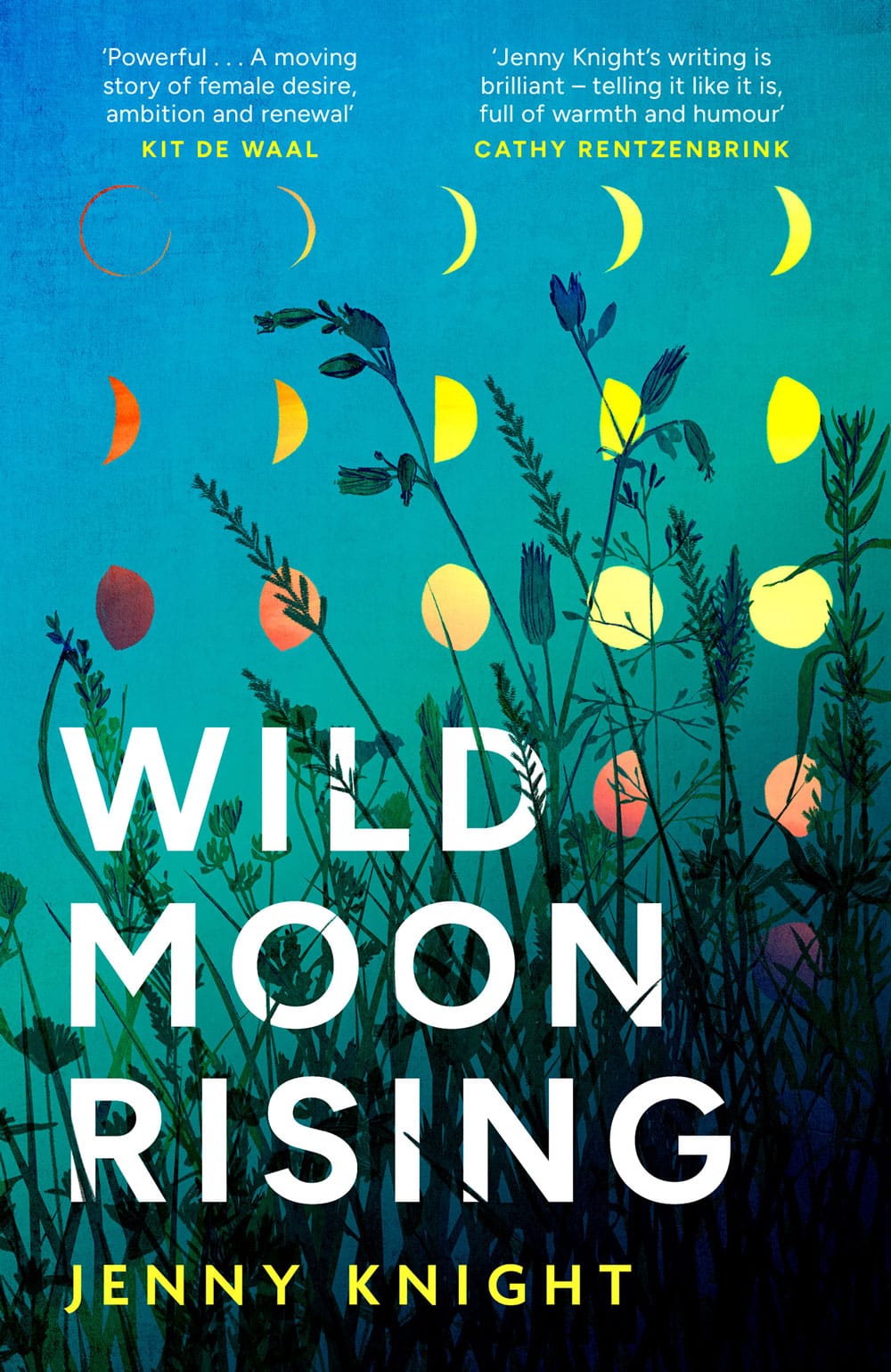

In her new novel, Wild Moon Rising, newly separated Claire moves back to Suffolk to a run-down rural cottage with a wild garden. Here she hopes to find solace and solitude and have some time to herself to reflect on her relationships with men and her former marriage, and to work out what comes next. In an unexpected turn of events, she ends up falling into friendship with Tansy, her octogenarian neighbour, under whose guidance she begins to bring her garden – and herself – back to life.

The Bee caught up with Jenny to discuss reframing female desire, ambition, wisdom and the solace of gardening.

Claire Malcolm: Your biography lists a wide variety of jobs that you’ve done. How do you get from working in a factory to a career as a published novelist?

Jenny Knight: That’s a good question! I’d wanted to go to drama school, but my folks were having none of that (education was the “way out”), and being the first in my family ever to go, I had no real idea what came after graduation. I loved writing and had a lot of acting and sketch writing under my belt, but what to do with that – with no contacts or cultural capital? After a gruelling time trying to live and work in London, I won a journalism traineeship in Ipswich – but I really didn’t want to be a reporter.

There followed many unhappy times trying to find my “thing” – my CV is a chequerboard, plus I could rarely afford to do just one job – before a chance to work for the Emergency Pastoralist Assistance Group, an NGO on the Kenya–Somalia border, which perked me back up. Back home, I got a typesetting job with a local editorial firm that led to copywriting (mostly household-name holiday brochures, which I did for years), worked for BBC local radio, then did freelance editorial after my first son was born.

With two small boys, I did a short story writing course just to escape one night a week – I had no time or energy for novels – and trained to be a part-time adult learning tutor. Then I won some competitions, one an Arvon course after which I wrote a novel and spent a lot of time being rejected. Rinse and repeat. I applied for Common People not expecting anything – and that was thegamechanger; I’d written a memoir by then and it all led from there.

CM: When you were growing up, was the idea of being a writer something that occupied you? Was it something that you thought was possible coming from a working-class background?

JK: I wrote my first “book” at seven, about a dentist talking a giant into having a gold tooth so he wouldn’t eat him. My mum was district nursing back then and took it to read to elderly patients – one, an ex-bursar of a school Princess Diana once attended, suggested helping me apply there, and the ensuing debates (I didn’t want to, and Mum wisely saw the issues I’d face) taught me a lot about class.

As a teen, music and acting were more compelling anyway, though writing was the thing I really excelled at. I wrote sketches at high school, again at uni, and loved writing. But as a job? Never! My sixth-form tutor told me not to bother applying to university; not to “kid myself about who I could be”. It was partly a desire to flick him the bird that drove me to work hard.

I got heavily into “exuberant” essay writing once at uni, and one personal tutor loved them – asking once if I’d ever considered being a writer. I laughed; it was that kind of inaccessible. I wanted to write comedy sketches and non-fiction then, but couldn’t see a way to do it.

So much of writing is about belief – the belief that you can, deserve to, aren’t just wasting time, and that people like you do this. In order to believe that, you need to see it – because you won’t get external validation very often, financially you’re on the back foot, and self-confidence is a huge issue for a working-class kid in a middle-class world.

CM: Your debut novel, Wild Moon Rising, has just been published. Often when debuts happen, we conveniently forget the long journey that a book has had before it gets into the hands of readers. When did you start writing the book?

JK: I began shortly before the pandemic – though not in any way writing the book it is now. I had a vague idea of something I wanted to do/say, and began writing thoughts, sentences, scenes, so when I sat down to write an actual book I had these tens of thousands of words – utterly daunting – of which only about ten percent are in the novel now. I applied for an Arts Council grant to buy time, and finally got one in 2021; late that year I could afford to begin properly writing – though this iteration of the book came to me in spring 2022. Once I knew what I wanted to do, I wrote it relatively quickly – I wish I could plot, but I have to write my way in and find the book in that way.

CM: Your novel is one of the first books published by Akan Books, a new publishing imprint led by June Sarpong. It was set up to “remove barriers and make space for voices and stories that have been overlooked”. How was the experience of working with them?

JK: I can’t praise Akan highly enough. I’ve had some awful experiences with publishers over many years, so I was wary, to say the least. But Akan have given me trust – in both the joy of writing and in the publishing process. They get it. They know how hard it is, they know how writers who want to be authors feel – what it’s like not to get feedback, or be ghosted, for example – and so they don’t do that. They offer a lot that most publishers don’t, and they care about their authors – it’s not just about the market, it’s about you as a person, a part of a team, and they want you to be happy. They’re strong women with strong views, and they’re committed to Akan 100%, but they’re also real people with real insight into what and how life is.

CM: Your novel has arrived at a time when women’s midlife experiences have gone mainstream, with dramas such as Jilly Cooper’s Rivals being such a hit, and with groundbreaking novels like Miranda July’s All Fours becoming bestsellers – plus other authors energising conversations about the menopause, midlife sexuality and relationships. Do you feel like you are part of a new movement?

JK: Yes – in that when I was writing Wild Moon Rising it felt like a total risk. I’d sit at my desk thinking, Who’s going to want to read this? High-profile women were hitting 50 and being laid off very publicly; older women actors weren’t getting roles – 84% of 50+ roles in Hollywood still go to men. We didn’t see older women being strong or main characters in books, and so on.

For me, it started with Kristin Scott Thomas’s Fleabag speech – I inadvertently air-punched at it – and it fascinated me to see, when I googled it, that it was the most searched-for speech of any in Fleabag. That, and the conversations I was having, overhearing or reading about with my peers and other women, made me want to write about this part of life – a sense of rage at being written off because we’re no longer ‘desirable’ or seen as relevant, with anything to offer. What kind of patriarchal, male-gaze bullshit is that? A man in his 50s writes a midlife crisis novel – it’s literature. A woman does it – and it’s ‘domestic’...

It’s a fascinating time in our lives: our mothers were not like us, so there’s no roadmap, but we have so much more life to live in this new, very liberating era – more new chapters to open. We are over half the world’s population, we have a good few decades left, and a very varied life experience to bring to the table. Women go through so many changes in life, and this part of the changing is both seminal and seismic. In other cultures, this is revered – as it once was here. Earlier this year I heard June Sarpong talking about her Ghanaian heritage, and explaining how in that culture women actually look forward to getting older – it’s seen as a badge of honour, a time of wisdom, respect, strength, prestige and power. They are the aspirational model.

Having been raised by women who fought for equality, and that famous 90s ‘women can have it all’ lie, women here now actually want to see it in action.

CM: You’re upfront about writing about sex, the workings of bodies, and how women’s bodies change as we grow up and age. Your character Claire tracks her life through her relationships, and her bold desires are not always socially acceptable – even to herself. Did it feel liberating to be writing about sex so openly and acknowledging the role of desire in shaping women’s lives?

JK: Yes. I’ve always found it strange – the dichotomy between what women acknowledge among ourselves – sex was, often still is, the famous 20-minute mark of a conversation – and how women’s desire is perceived societally. None of us felt immune to that, whether that desire was rampant or stagnant. It surprises me that in the 21st century, girls still worry about being seen as “freakish”, “dirty” or “slutty” for having or expressing strong desire.

For around half a woman’s life, we are shaped by our reproductive cycles, so there are times when we are as subject to the animal in us as men are openly acknowledged to be – and that doesn’t always respond to the ‘sensible’ stuff of the brain. Hence, some of our choices.

Desire is hugely important to women, in my experience – and complex, too. Often, it’s being desiredthat creates desire, and we definitely desire different things at different points in life. There is a great deal of the primal still in us, and a lot of women hold this in secrecy. It felt liberating to just write it. In your 50s, no one expects you to write sex as titillation, either. I wanted it to be honest and as ‘wild’ as it can be – good and bad.

In some ways, that goes against the norm and social perception – which appealed. It felt almost transgressive, rebellious – a lot of post-menopause echoes the teenage-girl self in this respect. Again, it felt like a risk – I’ve several friends who didn’t like that aspect of WMR, and who openly said sex didn’t bother them anymore. “Just give me the dog and a cup of tea, thanks...” But I do feel for many of us, it’s as if we redefine and reclaim the whole self again, rather than the roles we may have played for years – and, very importantly, once we’re free of cyclical hormonal input.

Fewer fucks given, as one of my editors said – if not necessarily less desire for sex!

CM: The two characters in your book find solace in each other, though they are of different generations, have very different temperaments, and are from different social class backgrounds – with Claire working class and Tansy solidly middle class. What made you interested in bringing together these two characters?

JK: I was interested in exploring intergenerational friendship – though initially, Tansy was a device to get Claire talking to someone! – and then came the different classes and temperaments, because I’ve been surprised in life by the unexpected value and joy that comes with these kinds of friendships. I had a male neighbour almost old enough to be my grandfather who, for years, I was very close to, and I’ve had both young and old friends through work, hobbies, writing, in my jobs in shops and pubs – friendships I’ve been both surprised and enriched by – so it was very much something that appealed.

A dear writing friend, much older than me – sadly dead now – advised me to keep in touch with the young as I aged too, or “you’ll have no idea how the world is working”. We have so much to learn from and give to one another – it’s another thing you realise as you get older: there is huge value and joy in being both the recipient and the giver of all this.

CM: Your novel feels class conscious to me, but it wears it very lightly. Was it important to have an exploration and acknowledgement of class feature as part of how we understand the characters?

JK: Yes. There’s a huge amount about where you come from which hits all over again in the second half of life. You begin to see things differently – in that, you have a deeper insight into how it affects life. As a younger working-class person, you want to believe that all you need do is be passionate, talented and hard-working to achieve your dreams. But as you age, you see how deeply unequal many things still are – how where you’re born and to whom affects the chances in life, but also the more subtle, deeply inner things like confidence, aspiration, self-belief.

Tansy and Claire are women from different places in life who’ve both felt restrained or held back by where they came from to an extent, and yet they bond and manage to explore this together. I wanted to examine that from Claire’s part, too – younger – because it is so hard when you find yourself, as a fellow Common People writer put it, trying to play your part in the middle-class world so unfamiliar to you: not knowing what to do, finding yourself still just tying your boots on the ski slope while everyone else is already hurtling down the slopes.

CM: The connections between postmenopausal women and their deep love and appreciation of gardening is well-trodden territory in both biography and fiction. What’s your take on this, and how did you decide to approach it in the novel? Are you a gardener?

JK: I had a big cottage garden previously – and I missed it badly: being able to go out and hack hell out of things, or rip them up, or dig holes and weed when writing wasn’t going well, or as a physical antidote to all the sitting. So I thought I’d give Claire a garden – also to give her something else to do, given she’s so solitary – and then I got to thinking how like life gardening is; a total storehouse of metaphor and analogy.

Then one day I looked up what one particular plant stood for symbolically, out of sheer curiosity, and that was a lightbulb moment. I felt like I’d found the key to a door. My mother is an amazing gardener, Dad grows veg, and I’ve always loved plants and nature, so I did get into gardening myself in my thirties – but I think older women come to feel that deeper connection with Mother Earth, as it were. Nature can’t be anything but feminine, so with gardening it’s about the creation of it, the nurture, the joy and satisfaction without the absolute drain of giving, caring or proving ourselves – it gives as much as it takes, and not many things in a woman’s life can claim that.

CM: Has the experience of publishing your debut novel and seeing it out in the world in the hands of readers lived up to your expectations? Has anything surprised you?

JK: It’s been such a surprise – all of it! I loved working with my wonderful editor, Hannah Boursnell, and I had no idea how vastly editing can improve your own book – even though I also work as a developmental editor! The validation of it all helped, too: it’s no longer a pipe dream, but an actual job – that changes a lot of things internally.

But I didn’t know what to expect, and I had no idea how completely terrifying it can be thinking about it being read. For so long, this was the goal – and then when it came, I felt more nervous than I could have thought. I also didn’t expect to feel so blown away by how it would feel to hold my book in my hands – that rendered me speechless. Or to see a box full of them, or see your name on the inside, your photo, your acknowledgements.

Among the most surreal and lovely surprises have been how it felt to talk about my book on a panel, or at my local writing centre; how supportive people are. And the really big one – how it feels to see it in a shop, or be asked to sign it. One thing I’ve learned for certain is that you are always, always learning in this writing life…

Read an extract from Wild Moon Rising.

And you can buy the whole beautiful thing at the Bee bookshop.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments