‘You can only live in the world you ken. The rest is just wishful thinking or paranoia.’[1]

Irvine Welsh was born on 27th September 1958 in Leith (although his birth certificate records his birth year as 1951).[2] His mother worked as a waitress and his father was a dock worker.[3] At the age of four, his family moved into social housing in the working-class district of Muirhouse in Edinburgh. The reality of his early years remains uncertain: Welsh became notorious for telling grandiose fabricated versions of his autobiography to journalists in the Nineties, after the success of Trainspotting.[4] Welsh disliked school and left at sixteen to move to London in the late Seventies, working a variety of manual jobs (dishwashing, portering, and paving roads among them) and playing in punk bands. At one point, he enjoyed a lucrative period of flipping houses: after being injured in a bus accident, Welsh received a £2,000 payout which he used to secure the mortgage on a flat in Hackney. This seed money funded his lifestyle as he navigated the booming London property market. In his early twenties, he experienced heroin addiction until quitting, ‘cold turkey’, at twenty-four.

After receiving a suspended sentence for vandalising a North London community centre,[5] Welsh returned to Edinburgh and completed an MBA at Heriot-Watt University, where his thesis was based on the creation of equal opportunities for women.[6] During this time he also worked in a senior role for Edinburgh Council’s housing department. His first piece of fiction – ‘The First Day of the Edinburgh Festival’ – was published in the New Writing Scotland anthology by editor Duncan McLean, who described Welsh’s style as ‘a kind of working class, everyday voice of the East Coast of Scotland’.[7] Trainspotting started life in this way: as a series of diary-entry style vignettes which were published separately in a variety of independent Scottish magazines, before being knitted together later by linking chapters. At twenty-eight, during the process of writing the book ‘proper’, Welsh experimented with injecting heroin again but has described the adverse effects as though ‘every single comedown had just come back’.[8]

After the staggering success of Trainspotting in 1993, Welsh published a collection of short stories called The Acid House (1994) and a second novel, Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995). These were followed by the three-novella series Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance (1996); the novels Filth (1998); Glue (2001); the Trainspotting sequels, Porno (2002) and Dead Men’s Trousers (2018); The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs (2006); If You Liked School You'll Love Work (2007); the first book in the Crime series (2008), later comprising The Long Knives (2023) and Resolution (2024); the short story collection, Reheated Cabbage (2009); the Trainspotting prequel Skagboys (2013); The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins (2014); A Decent Ride (2015); The Blade Artist (2016); and Resolution (2024). In addition, he wrote the plays Headstate (1994); You’ll Have Had Your Hole (1998); and, with Dean Cavanagh, Babylon Heights (2006).

Welsh is also a vocal antiestablishment advocate, known for his high-profile run-ins with the law. As McLean describes it in the Vice writeup: ‘He’d have a book out, and a week later he’d be arrested at a Hibs game, and it would be in the paper.’ Similarly, Welsh developed a penchant for penning profane letters to The Scotsman under increasingly outlandish pseudonyms. In a 2023 piece for UnHerd, he wrote: ‘The decline of class politics and its replacement by the schisms of identity is an integral part of the neoliberal order […] White working-class males are now recast as the establishment’s salivating attack dogs; the overseers of imperialism, enforcing the bidding of their wealthier masters. Their role in securing most of our human rights – through workplace struggle in the trade unions, strikes, demonstrations, wars and riots – is to be erased from our collective consciousness.’[9] Welsh is an important figure on the Scottish arts and literature circuit as a patron of Leith Theatre and the experimental Neu!Reeki! collective in his hometown of Edinburgh, which supports the new generation of practitioners in poetry, animation and music.

His first marriage to Anne Antsy (to whom the first edition of Trainspotting is dedicated) ended in divorce in 2003, as did a second subsequent marriage to Beth Quinn in 2018.[10] He married Emma Currie in 2022. Welsh spent most of the last decade living between Chicago and Miami but now lives in Oxfordshire.

Publication

Publishing’s capitalisation on the end of the ‘rights ay working people’ in Scotland?

‘Scargill’s got the megaphone and he launches intae one ay his trademark rousin speeches that tingles the back ay ma neck. He talks aboot the rights ay working people, won through years of struggle, and how if we’re denied the right to strike and organise, then we’re really nae better than slaves. His words are like a drug […] these c*nts really want us deid.’[11]

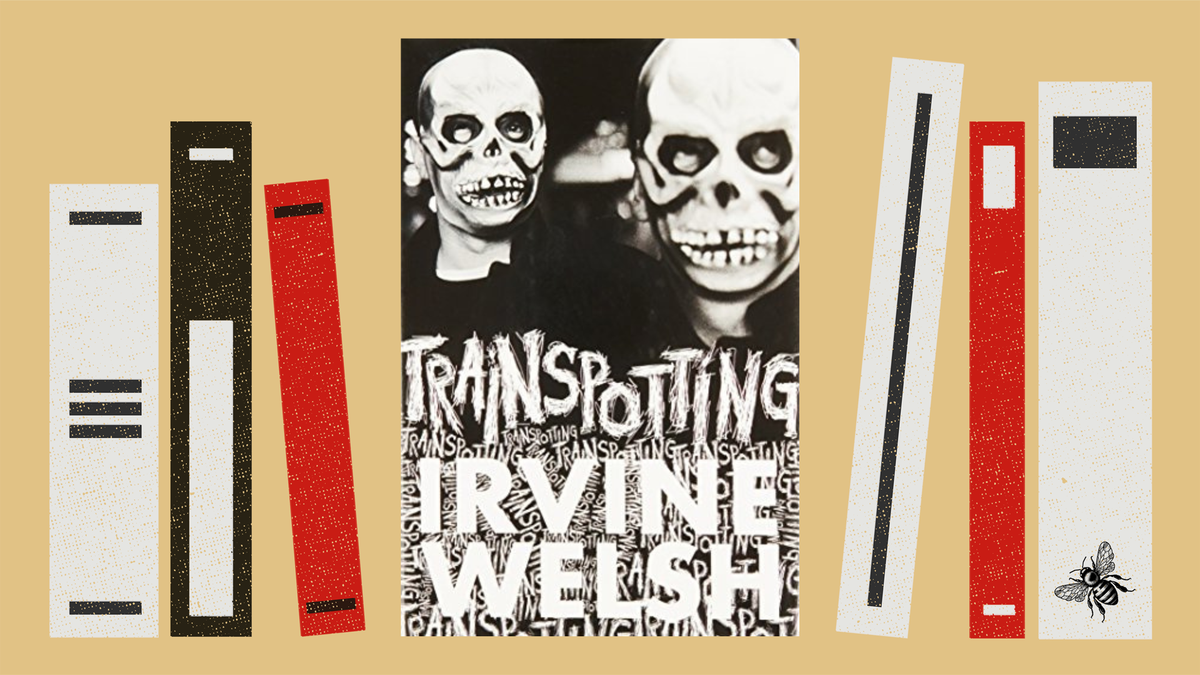

Trainspotting was published in August 1993 by Secker and Warburg (now Harvill Secker, an imprint of Vintage owned by Penguin Random House following a series of mergers and acquisitions in the late Nineties and early Noughties). It had an initial print run of 3,000 copies and appears to have gone straight to paperback. Ordinarily, new titles will be published as B format paperbacks for their second edition, but Trainspotting does not look like a B format – given that it has French flaps, I would guess that this first edition was a Royal paperback, which is slightly larger. This is an interesting decision, and one which may have been spearheaded by the author as paperbacks were considerably cheaper to print than hardbacks and thus retailed for less. (Nonetheless, Trainspotting remains the ‘most shoplifted novel in British publishing history’, according to The Guardian.)[12]

The cream-and-red cover features a photograph of two young men wearing skull face masks and an extensive quote from Glaswegian novelist Jeff Torrington, famous for his novels Swing Hammer Swing! (1992) and The Devil’s Carousel (1998), both focused on the lives of working-class Scots.[13]The back cover is a slightly unnerving headshot of Welsh, with his name underneath.

Welsh has been vocal about the fact that he has never had (and continues not to have) an agent, so Trainspotting made its way to Secker and Warburg’s then-editorial director Robin Robertson via a recommendation from Duncan McLean.[14] Robertson acquired the novel, despite allegedly believing it was unlikely to sell any copies at all. In reality, the novel was an almost instantaneous success, and to date has sold more than a million copies in the UK alone and translated into more than thirty languages.

Why, then, did an experimental novel from a complete newcomer pegged to sell poorly generate sales into seven figures in a pre-social media marketing era, seemingly in an instant? The most popular response is that it spoke to a demographic so often overlooked by mainstream publishing; in Jenni Fagan’s words, it vividly represented ‘a world that I recognised, and a language that I recognised, written in a way that I recognised’.[15] However, given Robertson’s hesitations, it seems unlikely that Secker and Warburg would have switched all their marketing engines on, so how was the book publicised? Or – and this is my hunch – is Trainspotting’s success a comment on how working class readers may not necessarily scour The Times Best Books of 2024 to dictate their next read, but rather source reading materials via a different, dynamic system of word of mouth? Picking up the themes of the Arthur Scargill quote, the power of people talking may be the answer. Trainspotting’s acclaim may also lie in the rapid production (and subsequent success) of Danny Boyle’s film of the same name, released to immense critical acclaim in 1996, which reached audiences who may not be regular consumers of the publishing industry.

The book’s reception amongst the middle-class world of publishing and prizes was similarly explosive. It was positively reviewed by Tom Adair in The Scotsman the week of its publication,[16] by Nicholas Lezard in The Independent the week before that,[17] and by Mark Jolly in The New York Times to coincide with the film release in July 1998.[18] Interestingly, The Herald does not appear to have reviewed the book during its first year. A month before its publication, however, Ian Bell wrote scathingly in The Guardian that Welsh’s prose was ‘flat, distanced, almost a monotone […] The shadow of James Kelman lies over Irvine Welsh’s first novel’; despite this, ‘the novel manages to draw great wit and energy from its wasted souls’.[19] Returning briefly to the point above, the fact that many reviews appeared in print in the lead-up to publication does suggest that Secker and Warburg went to the trouble of securing publicity for Trainspotting by way of disseminating proof copies to major news publications.

Despite these high-profile reviews, Trainspotting missed out on the Booker Prize shortlist that year for allegedly offending judges with its profanity and graphic scenes, such as the death of baby Dawn and one iconic moment in which Renton combs through his own excrement to retrieve heroin suppositories.[20]

The tip of the ‘drugs and literature’ iceberg

As Welsh himself put it, ‘The horrible thing is that Trainspotting was supposed to be a cautionary tale in some ways […] 30 years on [it] almost becomes some kind of inspiring clarion call: let’s do fucking drugs, man. We’re fucked anyway. Let’s just go for it.’[21]

However, perhaps it is reductive to cast Trainspotting as stratospherically successful in large part due to its risqué and graphic encounters with hard drugs. Rather, my hunch is that it is precisely these encounters set within its specific class and time context which has sustained the novel’s resonance for generations of readers. Commercially, too, it did not make sense; short stories rarely sell, and even the tenuous links between Trainspotting’s chapters fail to really cement it as a cohesive and linear narrative. Like George Gissing’s works, there may be an element of the privileged middle-class reader vicariously ‘cosplaying’ the lived experience of 1980s Muirhouse heroin addicts, but Trainspotting nonetheless catapulted this representation into the literary mainstream in a way that fundamentally changed the shape of Scottish (and British more broadly) fiction for years to come.

Welsh’s is a novel in direct contrast to the predominant representation of drugs and drug-taking in earlier literature, from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s opium-inspired ‘Kubla Khan’ to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde written during a six-day cocaine binge by Robert Louis Stevenson.[22] Charles Baudelaire even founded the Club des Hachichins in the 1840s, a collective of intellectuals who engaged in opium use to generate what they called ‘fantasias’, or psychedelic visions which could fuel their artistic pursuits.[23]

The prevalence of drugs in British literature was almost always ‘respectable’ by virtue of the arenas in which it took place – largely the homes of middle- to upper-class men, and often to fuel the creative spirit in the production of works of genius. (This does, of course, overlook changing historical attitudes towards what substances constitute ‘drugs’; Coleridge, for example, was prescribed laudanum to manage what may have been chronic pain.)[24] In the twentieth century, too, upper class novelists such as Edward St Aubyn regularly used heroin, whose depiction featured prominently in the Patrick Melrose novels (a loosely fictionalised character bearing a heavy resemblance to Aubuyn himself, as well as events in his own life).

So too might we consider there to be a Scottish literary heroin tradition: Alexander Trocchi wrote openly about his heroin use in the 1950s during his time in Paris. More recently, Will Self’s 2019 auto-fictional biography Will was reviewed in The Telegraph as ‘a deliberately repulsive portrait of the author’s junkie years’ and praised for its literary conceit, stopping just shy of the suggestion that Self’s heroin addiction was in some way a brilliant and deliberately engineered artistic move.[25] In the aftermath of Emerald Fennell’s 2023 film Saltburn, a rash of reporting sprang up devoted to increased scrutiny of British ‘narco-toffs’ whose heroin-fuelled escapades (often literary) were an open secret among the upper classes.[26]

In energetic contrast, Welsh’s Skag Boys operate in profoundly different class and physical contexts. Arguably, the historical moment at which the book appeared was during a psychotropic zeitgeist either triggered or amplified by the economic crises of the Eighties and Nineties; general studies have indicated that during economic downturn, young people are more likely to consume illegal drugs in a specific way.[27] Even more strikingly, there is a distinction in precisely which drugs are consumed more frequently during these periods: while cannabis and amphetamine use increases during recessions, sales of more expensive drugs like cocaine and heroin decrease.[28] At the end of the debilitating Seventies recession, however, markets were flooded by the supply of cheap heroin from Pakistan, which travelled straight to the UK’s heroin-producing hub: Edinburgh.[29]

During the late Nineties, in UK urban areas with such established user/dealer networks – specifically Edinburgh – heroin deals were pitched at between £5-10 (approximately £10-20 today) and popularised by the alternative music and club scene. A 1998 Home Office review into contributing factors for increased heroin use during this period was linked to ‘a dearth of services for young people in general’.[30] The study also makes a clear link between heroin usage in the Eighties and Nineties and ‘acquisitive crime, notably burglary, shoplifting, fraud and theft’. Trainspotting responds to this in interesting ways; strikingly, that the very final scene depicts Renton ‘stealing’ from Sick Boy in order to break the cycle of addiction. The distinction between state and social deviance is thereby inverted by the novel in a way that spoke to communities which have been particularly marginalised by both government policy and publishing.

Dialect: From patronising ‘gimmick’ to counter-culture manifesto

Perhaps one of the key factors for Trainspotting’s shock emergence as a publishing underdog is its episodic structure and heavy reliance on Dunediner dialect, which makes for a powerful reading experience for the uninitiated – and a stark departure from other Nineties bestsellers, including Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and the second Harry Potter book from JK Rowling.

Pithily, in a piece for the Royal Literary Fund, Ray French writes, ‘Just what is publishing’s problem with British dialect? It seems that American and Caribbean English are seen as “exotic”, while British regional dialects are not. In publishing a regional accent is still a rarity, and how can that monoculture not percolate through to some extent into the attitudes of people who work in it? Publishing has finally, belatedly woken up, to some extent at least, to its blind spot about race, but there’s still progress to be made when it comes to class.’[31]

Publishing is ripe with examples of authors toning down dialect on the advice of their editors; Charlotte Brontë herself obliged when her publisher asked her to amend her sister Emily’s Wuthering Heights with a view to excising much of the dialect, in order to appeal to southern readers.[32] There may also be a problem with regional working-class dialects appearing as a kind of gimmick within fiction written by middle-class writers. For example, the playwright (and baronet’s daughter) Nell Dunn wrote most of Poor Cow in Cockney slang she learned from her fellow factory workers in Battersea in the Sixties.

More recently, American novelist Kathryn Stockett was criticised for remarks she made about co-opting a Black Southern US dialect in her novel The Help as a self-described ‘privileged, spoilt little white girl’.[33] During a public event at the Dallas Museum of Art, Stockett is quoted as having said, ‘You learn the turn of a phrase and, if you read it enough, you can rip it off […] There are those who are truly gifted – Hemingway, Steinbeck – but really, I’m just makin’ shit up.’[34] It should be noted that these alleged comments have appeared on multiple blog sites online as opposed to being reliably reported; they should also be considered in their national and racialised context, perhaps more so than their class context. However, there is an important cultural myth to be aware of here, in that writing dialect risks being received as the preserve of ‘clichés, sentimentality, and stereotypes’ and avoided in more ‘literary’ (read: all too often middle-class) fiction today.[35]

Trainspotting could hardly be characterised as ‘sentimental’ fiction, presenting instead a dialect which empowers as opposed to patronises working-class vernacular from the inside, as it were, which may speak to its resounding success amongst a demographic so excluded by mainstream publishing. Indeed, its indelible position in literary history amongst such counter-culture titans as Rebel Inc. magazine, founded by Welsh’s friend and associate Kevin Williamson, cements its appeal for both working-class and perhaps disillusioned (or rebel-without-a-cause) middle-class readers, who migrated between the alternative publishing and music scenes of the Nineties. (Rebel Inc. famously printed an unedited three-hour-long interview between Welsh and Williamson in 1993 during which both took an ecstasy pill.)[36]

In an interview for Renaissance One, during which Williamson was asked which creative masterpiece he wished he had written, his answer was immediate: ‘Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh. It’s more than the sum of its pages. It was a weaponisation of working class culture and internationalised the legitimacy of the Scots language.’[37] Strikingly, after James Kelman’s dialect-heavy novels A Disaffection (1989) and How Late It Was, How Late (1994) won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction and the Booker Prize respectively, the Scottish novel experienced a major cultural revival with a clear emphasis on working-class experiences. This was in contrast to the literary darlings of Nineties London, who largely comprised white, wealthy, male themes produced by authors famously including Ian McEwan, Martin Amis, and Julian Barnes.

As one Prospect essay puts it: ‘It’s now almost funny to think that Martin Amis was once considered the bad boy of British fiction. Welsh tends to have made news for being arrested at a football match in Glasgow, or for distressing passengers on a train to Exeter, rather than sacking his literary agent or falling out with Julian Barnes. More importantly, though, the controversies that have dogged this lanky, shaven-headed Hibernian supporter involve a fictional treatment of underworld substance abuse, sexual depravity and recidivism that makes the armchair macabre once practiced by Amis and Ian McEwan seem a mere brand of nastiness-lite.’[38] More than this, however, is the suggestion that what has truly defined Trainspotting as the novel for a generation is the runaway success of the Danny Boyle film.

Class, cults, and ‘the Queen’s fucken English’

The idea of the ‘cult novel’ is an imperfect science. Why Trainspotting should continue to endure today as opposed to novels such as Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son or Luke Davies’s Candy – both of which follow the exploits of a group of individuals deep in the grip of heroin addiction in 1970s Midwest America and 1990s Sydney – is tricky to define. Both texts were adapted as commercially successful films in the early 2000s (perhaps off the back of Trainspotting’s success?), with Jesus’s Son starring Billy Crudup and Candy starring Heath Ledger. However, although each novel was billed as a bestseller, neither appears to have achieved cult status within their respective national contexts in quite the same way as Welsh’s novel. Johnson himself allegedly called Jesus’s Son ‘a rip-off of Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry’: a twentieth-century Russian literary classic, set during the Russian-Polish campaign.[39]

All this is to suggest that how and why certain texts become ‘cultish’ is not a question of the simple grouping of certain themes or even qualities. Academic Joseph A. Barrerira has written on cult novels, suggesting that ‘cult fiction originates outside the production of the literary establishment. It is a type of fiction that inspires quasi-religious fervour from its readers – the cultists – a fervour that is not of the ephemeral or trivial type, but one that grows exponentially over a long period of time, thus an essential component of a particular work of fiction’s “cult” status.’[40]

Similarly, Kelly Fann writes: ‘This is what cult fiction books do to their faithful followers: they inspire, amuse, and amaze their readers, they stir the emotions and mesmerize, they evoke passion, and they etch themselves into their reader’s memory.’ There is thus something ethereal, some mood or quality which appeals to the senses and emotions, that is difficult to qualify here. Another major reason for cult status is that these texts ‘defy standard genre classification […] a classic genre bender’ which tends towards the groundbreaking, ‘either through its prose style or through the subject matter the author has chosen to discuss. Subjects often cover lurid topics such as sex and drugs, or will include criticism of the establishment through exploration of the human condition or creation of dystopian societies.’

These texts erupt into the literary institution, apparently without warning (although, as we have seen above, Trainspotting may actually have tapped into the incipient strains of a broader global literary trend). They are controversial or titillating – often both – which grabs attention. Bonus points if they are banned somewhere. More than anything, these texts address themselves to socially disenfranchised readers – however, in light of Trainspotting, I would suggest that over time these readers may not be actually disenfranchised (e.g. middle or upper class teenage boys for whom Trainspotting has attained a kind of cult gritty glamour) but may rather feel themselves to be.[41]

Exploitation

Trainspotting is one of a few literary texts whose cinematic adaptation is perhaps as well-known as the novel itself. Its adaptation was the brainchild of filmmaking team Danny Boyle, Andrew MacDonald and John Hodge, who were looking for a project to follow up their BAFTA award-winning 1994 film, Shallow Grave.[42] Although a stage-play was already showing at London’s Bush Theatre, the film rights had already been sold to Noel Gay who had no plans to actually dramatize the novel, but wanted to be co-producers in light of all the hype around Boyle, MacDonald and Hodge. Hodge drafted the script, as Welsh allegedly asked to have no part in it (but was apparently pleased by the purchase – as MacDonald recounts, ‘When Irvine heard about our plans, he wrote us a brilliant letter saying we were the greatest Scotsmen since Kenny Dalglish and Alex Ferguson.’)

With a budget of £1.5 million courtesy of Channel 4, the rights were finally secured by Spring 1995 and pre-production could begin. ‘One of the key issues was not to make a film that cost a lot of money. You can get carried away with people offering you money and end up making a film that's out of proportion with your kind of audience,’ Boyle commented at the time; as a result, over the following seven weeks, they worked to source a cast from relatively unknown actors as closely resembling the novel characters as possible. The majority of the crew were Edinburgh locals. Ewan McGregor was cast first as Renton, having previously starred in Shallow Grave. He was then followed by Ewen Bremner as Spud and Bobbly Carlyle as Begbie. Despite Jonny Lee Miller’s upbringing in an affluent borough of London (Kingston), he was finally cast as Sick Boy. To locate a suitable teenage Diane, flyers were shopped around clubs, clothes stores and hairdressers advertising the part. Nineteen-year-old Kelly MacDonald landed the part after one caught her eye during a bar shift she was working. The cast were not subject to drastic diets to alter their appearances, but were asked to abstain from alcohol during filming.

Filming commenced in June 1995 around Glasgow and Edinburgh and lasted just over a month. MacDonald, Hodge, and Welsh all played cameos: MacDonald a prospective London tenant, Hodge the police officer in pursuit of the Skag Boys in the opening scene, and Welsh as Renton’s drug dealer. Editing took eight weeks. During this process is when the lines between text, film, and music started to blur: MacDonald was the brains behind securing the now-iconic soundtrack, negotiating with indie bands and celebrities alike to engineer the perfect soundscape. Miraculously, all the tracks were donated or licensed for use within the film’s total budget; four tracks were composed from scratch for the purpose. Allegedly, Oasis did not contribute anything towards the soundtrack as Noel Gallagher believed the film was about actual trainspotters.[43] As established, Welsh was well-known on the acid house and rave circuit also populated by the big hitters in Britpop, which may have been a further connection used to broker the soundtrack. As Boyle put it, ‘One of the ways we can actually identify the period is to move from Iggy Pop through to dance music […] The film’s timespan is impossible because Renton doesn’t age and they don’t cut their hair, but you feel you’ve moved through a period of time on a sensual rather than documentary level.’[44]

Interestingly, the Trainspotting poster design was part of a Student Railcard promotion deal, whereby students could exchange an HMV voucher for one of eight pre-selected posters after purchasing a railcard. This gestures firmly towards the target market: young, energetic British twenty-somethings (although still troublingly drawn along class lines given higher education’s status as the preserve of the wealthy; just a year later, Tony Blair’s government would reintroduce tuition fees and the students loans system.)[45] The film was finally released in February 1996, following a rejacket of Welsh’s novel as a tie-in, and was an immediate success: its gross worldwide was close to £13 million, or just over £30 million today. It remains the eighth highest-grossing UK film to date.

Trainspotting’s sex appeal – primarily in the form of its leading cast and soundtrack, courtesy of big Britpop names in vogue – lent it a popularity amongst younger people which catapulted it into the mainstream in a big way. In part, this was because of the precise ways in which Boyle framed the collision of music and cinema. Rejecting a more traditional cinematic sound-piece, he instead prioritised tracks which spoke to the novel’s themes of intense or exaggerated reality under the influence of addiction. The majority of artists featured on the soundtrack were explicitly namechecked in Welsh’s book, creating a strikingly meta cinematic text.

The film also coincided with a noteworthy cultural moment as the economy was steadily growing, on top of which young people were significantly discouraged from drug-taking by certain high-profile drug-related deaths. The death of Leah Betts in particular – an Essex teenager who died after taking an ecstasy pill and drinking an unsafe quantity of water – triggered an outpouring of anti-drug sentiment.[46] In the nearly thirty years since the film’s release, it has become a favourite of Reddit film subreddits and online forums, on which users discuss the novel and film’s enduring popularity. Broadly, the general impression from these posts is that Trainspotting captures the lived experience of addiction for a reader or viewer who may be unfamiliar, without necessarily perpetuating typical stigmas associated with heroin addiction. For example, Lesley and Sick Boy are not demonised for their parental neglect but instead shown to be grieving the accidental death of their baby, Dawn.

What is especially interesting about Trainspotting’s acclaim, then, is that it detailed an experience which many of its viewers were not necessarily having, but its popularity still endured, perhaps evoking broader claims on the power of peer groups and drug culture (if not consumption) in the Nineties.

Other media

Boyle’s critically acclaimed film was followed in 2017 by T2 Trainspotting, produced again by the Boyle, MacDonald and Hodge dream team. Based on Welsh’s sequel Porno and set twenty years on, Renton – now a successful nightclub owner – returns to Edinburgh where Spud is on the cusp of divorce, Sick Boy has inherited a failing pub, and Begbie has just been released from prison. The film inverts ideas of authorship, ending with Spud composing a memoir provisionally titled Trainspotting. With a production budget of £18 million, T2 was a commercial success, grossing £17.1 million in the UK and £31.9 million worldwide.[47]

The novel was also adapted by Harry Gibson to create Trainspotting Live, a 75-minute immersive experience billed as ‘no-holds-barred immersive, in-yer-face theatre [which] left Irvine Welsh feeling “blown away”’.

Perhaps most surprisingly, a musical adaptation of Trainspotting is scheduled for the near future. Together with songwriting-producing duo Steve McGuinness and Phil McIntyre, in his own words, Welsh was initially unconvinced: ‘[Phil McIntyre] kept saying to me: “We’ve got to do Trainspotting as a musical.” I just said to him: F*** off, you couldn’t do it as a musical. But maybe once a year he would send me a little card with “Trainspotting the musical” written on it. I just thought: Well, in a few years’ time, I am going to be an urn on some poor b_______ mantlepiece and (someone like) Andrew Lloyd Webber is going to come along, so maybe I should be the one that makes the money.’[48]

Choose Irvine Welsh, a documentary on the author’s Edinburgh childhood, was released in 2023.[49]

Further reading

In addition to the footnotes, the below articles may of particular interest:

Jeffrey Karnicky, ‘Irvine Welsh’s Novel Subjectivities’ in Social Text 21:3 (2003)

- Establishes a canon of Scots versus ‘the Queen’s fuckin English’ within Welsh’s texts, from Trainspotting to Filth, alongside drawing a throughline to his main characters’ frequent existential angst and how this is worked out through ‘non-standard’ dialect.

Aaron Kelly, Irvine Welsh (Manchester University Press, 2005) - Part of the Contemporary British Novelists series, this is one of the first full-length studies of Welsh’s canon with an eye on the contextual conditions surrounding its development. Kelly locates him as a seminal figure within the ‘brat pack’ of influential Scottish writers and actors in the Nineties, based on an extended interview between Welsh and the author in 2004.

Hele Priimets, ‘Non-standard Language in Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and in Olavi Teppan’s Translation of the Novel into Estonian’, CORE MA thesis database (2017) - Priimets does not appear to have published her thesis more widely post-graduation, but makes a fascinating case for the translatory choice not to substitute the strong dialect in Trainspotting for a regional Estonian equivalent as in most translated editions of the novel, instead employing Standard Estonian which incorporates an informal register and phonetics. (Notably, Trainspotting has never been ‘translated’ into ‘Standard English’.)

Ed Day and Iain Smith, ‘Literary and biographical perspectives on substance use’ in Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (2018) - Maps out a possible relationship between substance use or abuse and the contexts of production around specific classic texts, including The Great Gatsby and The Bride of Lammermoor. Day and Smith consider the theory that there is something about ‘the creative character’ that lends itself to engagement with certain drugs, especially alcohol, cocaine and opium.

Irvine Welsh, Filth (Jonathan Cape, 1998) ↩︎

‘Irvine Welsh’, British Council for Literature <https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/irvine-welsh> [accessed 7 August 2024] ↩︎

Simon Hattenstone, ‘Irvine Welsh: “When you get older, it’s harder to be a bastard”’, The Guardian (17 March 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/17/irvine-welsh-when-older-harder-be-bastard> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

Tristan Kennedy, ‘How Irvine Welsh Went from Enfant Terrible to the Scottish Tourist Board’s Favourite Guy’, Vice (18 December 2019) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/irvine-welsh-profile-scotland-trainspotting/> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

‘Irvine Welsh’, Waterstones <https://www.waterstones.com/author/irvine-welsh/12925> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

Craig Lamont, ‘Irvine Welsh’, Oxford Bibliographies (24 February 2021) <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199846719/obo-9780199846719-0170.xml> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

Tristan Kennedy, ‘How Irvine Welsh Went from Enfant Terrible to the Scottish Tourist Board’s Favourite Guy’, Vice (18 December 2019) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/irvine-welsh-profile-scotland-trainspotting/> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

Tristan Kennedy, ‘How Irvine Welsh Went from Enfant Terrible to the Scottish Tourist Board’s Favourite Guy’, Vice (18 December 2019) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/irvine-welsh-profile-scotland-trainspotting/> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

Irvine Welsh, ‘The betrayal of white working-class men’, UnHerd (27 May 2023) <https://unherd.com/2023/05/irvine-welsh-the-betrayal-of-white-working-class-men/> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

Teddy Jamieson, ‘“I hated Thatcher, but I was one of the people who benefited. It was a kind of liberation”’, The Herald (14 April 2012) <https://www.heraldscotland.com/life_style/arts_ents/13055436.i-hated-thatcher-one-people-benefited-kind-liberation/> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

Irvine Welsh, Skagboys (Jonathan Cape, 2012), pp. 12-13 ↩︎

Simon Hattenstone, ‘Irvine Welsh: “When you get older, it’s harder to be a bastard”’, The Guardian (17 March 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/17/irvine-welsh-when-older-harder-be-bastard> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

‘Swing Hammer Swing, blow by blow’, The Herald (1 February 1993) <https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12623330.swing-hammer-swing-blow-by-blow/> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

‘Irvine Welsh’, BBC Two Writing Scotland (September 2004) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/profiles/27h8d0xjjCVtTSnW5zbNF0V/irvine-welsh#:~:text=Duncan McLean recommended Welsh to,it was unlikely to sell> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Tristan Kennedy, ‘How Irvine Welsh Went from Enfant Terrible to the Scottish Tourist Board’s Favourite Guy’, Vice (18 December 2019) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/irvine-welsh-profile-scotland-trainspotting/> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

Tom Adair, ‘Tom Adair reviews Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh’, The Scotsman (5 September 1993) <https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/books/from-the-archives-tom-adair-reviews-trainspotting-by-irvine-welsh-1458416> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Nicholas Lezard, ‘BOOK REVIEW / Junk and the big trigger: “Trainspotting” – Irvine Welsh: Secker, 8.99’, The Independent (28 August 1993) <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/book-review-junk-and-the-big-trigger-trainspotting-irvine-welsh-secker-8-99-1464158.html> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Mark Jolly, ‘Books in Brief’, The New York Times (28 July 1996) <https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/01/05/13/specials/welsh-trainspotting.html> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Ian Bell, ‘Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh review – last exit to Leith’, The Guardian (15 August 1993) <https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/1993/aug/15/featuresreview.review> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Craig Lamont, ‘Irvine Welsh’, Oxford Bibliographies (24 February 2021) <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199846719/obo-9780199846719-0170.xml> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

David Barnett, ‘“Choose drugs?” 30 years after he wrote Trainspotting, Irvine Welsh says life is tougher now’, The Guardian (2 July 2023) <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jul/02/trainspotting-author-irvine-welsh-book-choose-life-young-people> [accessed 14 August 2024] ↩︎

Mark Townsend, ‘Drugs in literature: a brief history’, The Guardian (16 November 2008) <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2008/nov/16/drugs-history-literature> [accessed 21 August 2024] ↩︎

Andrew Hussey, ‘Heroin: art and culture’s last taboo’, The Guardian (22 December 2013) <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2013/dec/22/art-heroin-christiane-f> [accessed 28 August 2024] ↩︎

John Worthen, The Gang: Coleridge, The Hutchinsons & the Wordsworths in 1802 (Yale University Press, 2002) ↩︎

Duncan White, ‘Will by Will Self review: a deliberately repulsive portrait of the author’s junkie years’, The Telegraph (9 November 2019) <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/what-to-read/self-will-self-review-deliberately-repulsive-portrait-authors/#:~:text=Will is the story of,twenties%2C hurtling toward rock bottom> [accessed 23 August 2024] ↩︎

Tom Sykes, ‘“Saltburn” for Real: Meet the Young, Rich “Narco-Toffs’” Who Party Hard’, Daily Beast (26 April 2024) <https://www.thedailybeast.com/saltburn-for-real-meet-the-young-rich-narcotoffs-who-party-hard> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

B Casal, B Rivera and C Costa-Storti. ‘Economic recession, illicit drug use and the young population: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis’, Perspectives in Public Health (2023) <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17579139231180751> [accessed 21 August 2024] ↩︎

Geert Dom et al. ‘The Impact of the 2008 Economic Crisis on Substance Use Patterns in the Countries of the European Union.’ International journal of environmental research and public health 13:1 (2016) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4730513/> [accessed 21 August 2024] ↩︎

Aida Edemariam and Kirsty Scott, ‘What happened to the Trainspotting generation?’ The Guardian (15 August 2009) <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2009/aug/15/scotland-trainspotting-generation-dying-fact> [accessed 28 August 2024] ↩︎

Howard Parker, Catherine Bury and Roy Egginton, ‘New Heroin Outbreaks Amongst Young People in England and Wales’, Home Office Crime Detection and Prevention Series Paper 92, edited by Barry Webb (1998) <https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/3604/1/Home_Office_New_heroin_outbreaks.pdf> [accessed 22 August 2024] ↩︎

Ray French, ‘In Praise of Dialect’, Royal Literary Fund (17 December 2018) <https://www.rlf.org.uk/posts/in-praise-of-dialect/> [accessed 28 August 2024]. ↩︎

The Letters of Charlotte Brontë: With a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends, Vol. 2: 1848-1851 ed. by Margaret Smith(Oxford University Press, 2000) ↩︎

Elizabeth Day, ‘Kathryn Stockett: “I still think I’m going to get into trouble for tackling the issue of race in America”’, The Guardian (9 October 2011) <https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2011/oct/09/kathryn-stockett-help-civil-rights> [accessed 28 August 2024]. ↩︎

Pamela Tooley Hammonds, ‘Lessons on Writing from Kathryn Stockett’, What Women Write <https://whatwomenwritetx.blogspot.com/2011/05/lessons-on-writing-from-kathryn.html> [accessed 28 August 2024]. ↩︎

Ed Davis, ‘The Transformative Power of Writing Dialect’, Writers Digest (12 July 2021) <https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/the-transformative-power-of-writing-dialect> [accessed 28 August 2024] ↩︎

Tristan Kennedy, ‘How Irvine Welsh Went from Enfant Terrible to the Scottish Tourist Board’s Favourite Guy’, Vice (18 December 2019) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/irvine-welsh-profile-scotland-trainspotting/> [accessed 8 August 2024] ↩︎

Melanie Abrahams, ‘Interview with Kevin Williamson, Neu! Reekie!’ Renaissance One (12 April 2017) <https://www.renaissanceone.co.uk/blog2/2017/4/12/interview-with-kevin-williamson-neu-reekie> [accessed 28 August 2024]. ↩︎

‘Irvine Welsh’, Prospect (19 May 2001) <https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/essays/56268/irvine-welsh> [accessed 28 August 2024] ↩︎

Nathan Scott McNamara, ‘Is “Jesus’ Son” a “Red Cavalry” Rip-Off?’, The Millions (20 January 2015) <https://themillions.com/2015/01/is-jesus-son-a-red-cavalry-rip-off.html> [accessed 2 September 2024] ↩︎

Joseph A Barreira, ‘The Cult Novel: Three Paradigmatic Cases—L’Immoraliste, Bonjour Tristesse, Extension du Domaine de la Lutte’ (December 2015) <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311543309_The_Cult_Novel_Three_Paradigmatic_Cases-L'Immoraliste_Bonjour_Tristesse_Extension_du_Domaine_de_la_Lutte> [accessed 2 September 2024] ↩︎

Kelly Fann, ‘Tapping into the Appeal of Cult Fiction’, Reference & User Services Quarterly (2011) pp. 15–18. ↩︎

Caroline Westbrook, ‘Trainspotting: The Complete Behind-The-Scenes History’, Empire Magazine (March 1996) <https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/trainspotting-behind-scenes-history/> [accessed 28 August 2024] ↩︎

Telegraph Reporters, ‘Noel Gallagher snubbed Trainspotting soundtrack “as he thought film was about railway enthusiasts”’, The Telegraph (18 October 2016) <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/18/noel-gallagher-snubbed-trainspotting-soundtrack-as-he-thought-fi/> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

Matt Glasby, ‘How Trainspotting’s iconic soundtrack shaped the film’, GQ Magazine (10 June 2019) <https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/trainspotting-soundtrack> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

Robert Anderson, ‘University fees in historical perspective’, History and Policy Policy Paper (2010) <https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/university-fees-in-historical-perspective> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

Katrina Chilver and Brad Gray, ‘Leah Betts’ tragic story that shocked a nation – and stopped many people taking drugs’, EssexLive (9 February 2024) <https://www.essexlive.news/news/essex-news/leah-betts-25-years-on-4704289> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

T2 Trainspotting (2017), The Numbers <https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/T2-Trainspotting-(UK)#tab=summary> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

Brian Ferguson, ‘Irvine Welsh lifts lid on plans for ‘Trainspotting the musical’ and a 30th birthday party in Edinburgh for the novel’, The Scotsman (12 October 2023) <<>> [accessed 29 August 2024] ↩︎

‘Irvine Welsh’s life and childhood in Edinburgh to be focus of new documentary’, Daily Record <https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/entertainment/irvine-welshs-life-childhood-edinburgh-27006815> [accessed 13 August 2024] ↩︎

Georgia Poplett is a researcher who worked with The Bee and New Writing North as part of a placement supported by the Northern Bridge Consortium, a Doctoral Training Partnership funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments