George Gissing’s youth: triumphs and tragedies

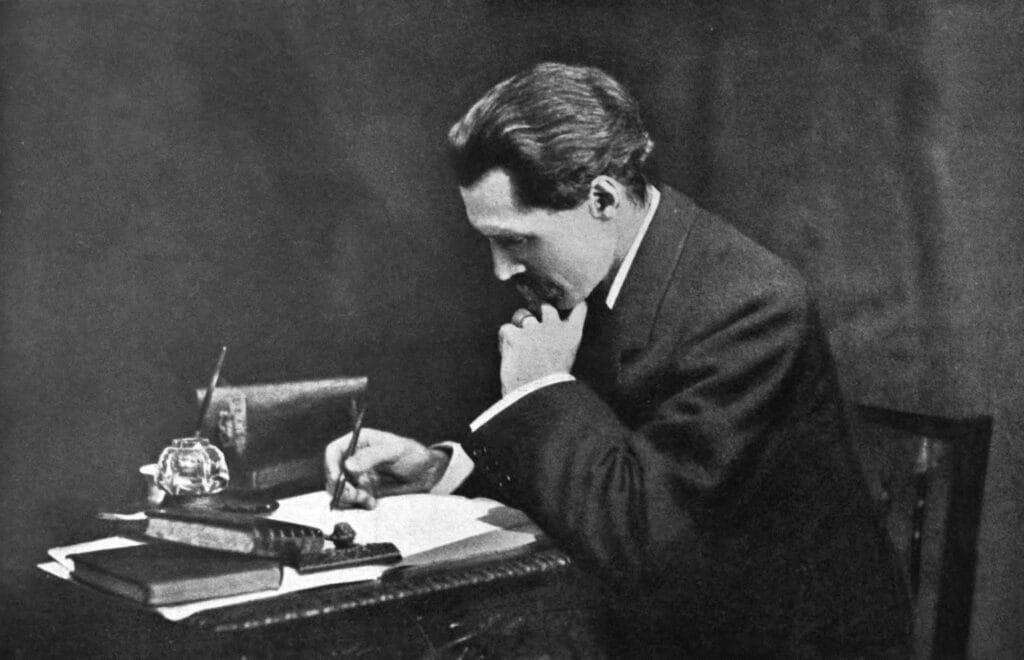

George Gissing was born in Wakefield, Yorkshire in 1857, the first of five children. His father came from a family of Suffolk shoemakers and ran a chemist’s shop until his death in 1870, when George was 13. George’s father had encouraged George’s studies, and George felt the loss keenly. Nevertheless, at 16 he won a scholarship to Owens College (later the University of Manchester), where his academic performance was initially outstanding, with his aptitude for English and Latin particularly noted.

In Manchester, Gissing met Marianne Helen “Nell” Harrison, who is reported by some sources to have engaged in sex work. Owens College expelled Gissing when it was discovered that he had stolen from other students to support Nell financially. After a month’s hard labour in Belle Vue Prison in 1876, he emigrated to Boston and then Chicago, serialising his short fiction in periodicals, including the Chicago Tribune.

On his return to England, Gissing married Nell and moved to London, working as a private tutor (the experience possibly providing inspiration for his New Grub Street character Harold Biffen). During this period, he self-published his first novel, Workers in the Dawn. In 1884, his and Nell’s marriage broke down, which some Gissing scholars have attributed to Nell’s alcoholism. Nell died in a Lambeth slum four years later. Gissing identified her body, but he did not attend her funeral.

Writing: a slow ascent

That same year, 1888, Gissing embarked on a tour of Italy, where he nurtured his love of classical literature. (In a now-discredited turn of events, Gissing was posthumously suspected of Jack the Ripper’s crimes in a 1975 out-of-print book by Richard Whittington-Egan, called Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Casebook. The Italy trip proved to be an alibi, overlapping with the dates of the London murders.)

Returning to London in 1891, Gissing met and married Edith Underwood, daughter of a Camden Town shopkeeper. Their first son, Walter, was born in 1891. The family moved to Exeter and Brixton before settling in rural Epsom in 1894, where the couple’s second son, Alfred, was born in 1896. There, Gissing socialised with the literati of the day, including writer HG Wells, and the renowned economist and reformist Clara Collet.

This second marriage was strained: Gissing accused Edith of violent rages and, in 1896, sent Walter to live with his unmarried sisters in Wakefield without Edith’s knowledge. The couple finally separated in 1897. Edith died in 1917 aged 46, in an asylum where she had been confined since 1902. It is not clear whether Gissing arranged for her confinement, or who otherwise funded her institutionalisation.

In addition to his tendency to sell off his copyright quickly, often at a loss, Gissing’s failure to negotiate timely payment schedules with his publishers – and his publishers’ failures to offer responsible royalties – forced him to produce one or more novels a year in order to live off his writing.

However, he began to live more comfortably off his earnings towards the end of his life. His literary star ascended, and he wrote prefaces for five of Charles Dickens’s novels between 1900 and1901. But his health worsened and, in 1898, he departed for Europe’s warmer climate, entering into a bigamous marriage with Frenchwoman and translator of New Grub Street, Gabrielle Marie Edith Fleury. On 28 December 1903, in Saint Jean de Luz, Gissing died of myocarditis.

Publishing: ‘A trade of the damned’[1]

New Grub Street was the ninth of Gissing’s 23 novels. His first – the three-decker Workers in the Dawn – was rejected by multiple publishers and ultimately self-published using the proceeds of a small family inheritance, but proved a commercial failure.

Over the course of his five subsequent works, Gissing developed his take on the popular Victorian condition-of-England form of fiction: a politically engaged genre reflecting on contemporaneous labour relations, the class divide, and industrial themes. Gissing’s version was characterised by the presentation of morally upright protagonists struggling in dismal economic circumstances, often contrasted with working-class characters to draw out class differences.

His second foray into this genre – The Unclassed, published by Chapman and Hall in 1882 – was another commercial failure. Of these first novels, Gissing sold his copyright outright for between £100 and £150 (around £15,000 to £23,000 today). This in an era in which the difference in the average annual income of the gentry and the working class was less than £300 per year.[2]

These, then, were the material conditions in which New Grub Street would be written. Gissing’s upfront payment from his publisher was £150, but off the back of its success Gissing was able to negotiate a £200 advance for his next novel, Born in Exile (1892). Towards the late 1890s he was making upwards of £350 per book.

Gissing first began work on New Grub Street in October 1890, and delivered the finished manuscript to publishers Smith, Elder & Co the following December. By April 1891, the novel was in print. It would become his most famous book, popularised in part by the later devotion of George Orwell.

Rare bookseller James Cummins reports that New Grub Street’s first print run comprised 500 to 750 copies. Exact figures are difficult to ascertain, but it is suggested that 390 of these were sold to lending libraries. Reviews of rare booksellers’ prices suggest that New Grub Street’s first print run actually involved closer to 500 copies, with a further 250 being printed for the second print run later in 1891.

New Grub Street, commercial fiction, and the rise of the lending library

In the early modern period under Queen Elizabeth I, all printing was banned outside of London, Oxford, Cambridge and York. After the lapse of the 1662 Licensing Act in 1695, the printing trade was stringently monitored for sedition by the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers, under the purview of the Bishop of London and the Archbishop of Canterbury.[3] Printing presses and their publishers were therefore largely circumscribed within the national centre of commerce – the City of London – around which communities of jobbing writers sprang up in the late 19th century.[4]

The title New Grub Street is an extended play on Grub Street, a London alley first described by Samuel Johnson and used as a metonym for commercial publishing, as Wall Street is used today for the stock market.[5] The name Grub Street originated from a refuse ditch that reportedly ran alongside the street, but soon came to signify what was produced from the pen of the so-called “needy scribbler”.[6] The real Grub Street is now known as Milton Street. It is beside the Barbican Estate in North London, an area in which some publishers still maintain offices.

The original Grub Street’s proximity to the British Library is also important – as seen in New Grub Street, the library became an important hub for writers in the 19th century. Grub Street writers usually resided in the garrets of buildings, which were cheap to rent owing to their cramped, sloped ceilings; damp and cold conditions under uninsulated roofs; and inaccessibility.[7] Similar conditions are found in New Grub Street, of course.

It was not easy for late Victorian writers to make money, and the economic pressure on them was intensified by the three-decker format. In Gissing’s period, novels were conventionally published in three volumes before being more cheaply reissued. Lending libraries like that of the well-known Charles Mudie insisted on a 12-month interval between editions, similar to the standard period of a year between hardback/ebook and paperback editions in publishing today. On their own, these three-volume first editions retailed at 33s/6d – equivalent to £114.68 today – but they were sold to the lending libraries at half price.

Mudie commonly bought at least 100 copies. The purchasing power of him and the other lending libraries could make or break a late Victorian writer’s career, forcing them to choose between enduring a slower production pace but making a guaranteed sale and accessing a much larger circulation of readers, or selling their copyright back to their publishers at a probable loss.

Gissing v ‘the triple-headed monster’

For example, Gissing saw reprint rights on New Grub Street of a halfpenny per copy up to 25,000 copies, rising to three-quarters of a penny thereafter. For reference, the average annual working wage in England in the mid-1880s is quoted as being £42/12s, or £6,860 today.[8] Lending libraries like Mudie’s generally charged their subscribers one guinea annually (£69.50 today). They enjoyed an effective stranglehold on the market of working-class and lower middle-class readers.[9]

Gissing’s feelings towards the three-decker format are perhaps embodied in Edwin Reardon’s hatred of “the triple-headed monster”: while three-volume novels paid more and were associated with more “literary” prestige, they demanded more time and energy to write than a single-volume novel. Indeed, Reardon estimates that one three-decker work generated the same income as four single volumes.[10]

Mudie and other circulating libraries favoured formulaic writing and stock plots as the century progressed, reducing the margins for more experimental novels until the Net Book Agreement of 1900, which dictated set prices for novels within the literary marketplace. Gissing’s first two rejections from Smith, Elder & Co cite their fear that neither book appealed to the Mudie reader, hence their commercial nonviability – recalling Jasper Milvain’s opening assertion that the “successful man of letters … thinks first and foremost of the markets”. Strikingly, New Grub Street’s first-edition title page copy emphasises Gissing’s credentials as a prolific writer of the three-decker as their marketing strategy.

Slum fiction and the origins of the mass market

Although the reading public was more evenly weighted between the upper, middle and lower classes in the aftermath of the 1870 Education Act, which made provision for children’s schooling between the ages of five and twelve, there is a question of time and labour here. As the middle classes gained additional leisure, the industrialisation of 19th-century life absorbed the working classes into increased labour. So when we think about who exactly was reading what became known as “slum fiction”,evidence suggests that it was fewer working- than middle- and upper-class readers, who may have approached these works as titillating portraits of poverty.

In an era of widespread wholesale slum clearance, did slum fiction play into certain sensationalised ideas about working-class life as received by the middle-class reading public, or did its popularity derive from its more accurate depiction of working-class life, which appealed to a newly-literate working-class public?

To help answer this question, we might look to the readership and circulation numbers of the literary periodicals in which Gissing’s work was reviewed. (Of note, too, is that, despite this expanded literacy, taxes on paper, newspapers, and advertising meant reading largely remained the preserve of the wealthy, as Frederick Nesta has explored.)[11]

Nesta estimates that, by the 1890s, “there was potentially an English-reading audience of 120 million” across the UK, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and India, as compared to only “50,000 only 65 years before”. This meant there was a market in which writers could try to sell the serial and translation rights for their work. However, as indicated earlier, Gissing appears to have followed the “gentlemanly” letter of an antiquated publishing age, engaging directly with Smith, Elder, and selling them his copyright outright.

George Smith (the Smith of publishers Smith, Elder) had Gissing to dinner at his home several times, often reminiscing about editing Charlotte Brontë in what Gissing apparently considered to be an insufficiently reverent tone. This is how publishing was done in the early 19th century, and it contrasts strongly with Milvain’s rather more commercial late-19th-century approach seen in New Grub Street. On the whole, it appears to have benefited publishers more than their authors.

What makes New Grub Street so prescient now is Gissing’s laying bare of the intersections of literary taste with the way writing is sold and distributed. Since the mid 1990s, we have been living through the greatest shift in mass reading habits and book production since the 1880s, many of those changes are not dissimilar to those in this great realist novel.

Amazon, controlling around half of all new-book sales in 2019, according to the Wall Street Journal, can be seen as a modern Mudie’s, although it also a publisher, with multiple book imprints, some of which like Audible dominate their sectors. In “Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon”, the literary scholar Mark McGurl argues that Kindle Direct Publishing is the “most dramatic intervention into literary history”, on the grounds that it allows writers to circumvent traditional gatekeepers and publish their own work.

“The rise of Amazon,” he says, “is the most significant novelty in recent literary history, representing an attempt to reforge contemporary literary life as an adjunct to online retail.” Add to this the impact of social media, from BookTok to literary subreddits, and you have another dispiriting turmoil for literary writers like the one that so depresses Reardon.

Women, snobbery and the market

The feminisation of the Victorian literary mass market during this period is also an important context, especially given the success of Gissing’s later novel The Odd Women (1893).[12]

Middle-class women made up a majority of the Victorian reading public, with “popular” novels (especially those of a Gothic persuasion, like Ann Radcliffe’s) attaining major commercial status. At the same time, the 1870 Education Act had swelled popular readership so that, culturally speaking, writers in the late Victorian era shifted away from the Romantic idea of the “lone genius” towards the model lower-brow working professional. In this new era, writing had shifted from the elite preserve of the genteel to be classed alongside the clerical work so despised by New Grub Street’s Amy Reardon.

Moreover, as Stephen Whiting shows, the intellectually inferior books now being produced for the mass market were not “envisaged as morally and culturally enriching [but] intellectually harmful”. Strikingly, as expanded literacy rates coincided with rising concerns around contagion and public health, classical literature was seen to epitomise moral and physical improvement in direct contrast to the popular penny dreadfuls and similar. This was in part the case behind Matthew Arnold’s influential arguments in Culture & Anarchy (1869).

Such literary snobbery was hardly new. Indeed, Daniel Defoe’s 1722 masterpiece Moll Flanders tried (unsuccessfully) to evade the Stationers’ Company’s censorship by occluding its less seemly (ie socially realistic!) qualities under the façade of “spiritual autobiography”.

Within this Church of England-sanctioned genre, a certain fall from grace was permissible in order to facilitate the necessary narrative arc of Christian redemption. However, in Victorian London, the genre of “hack” writing being produced out of Grub Street was remarkable for the fact that working-class readers were now able to purchase and read about the lives of working-class characters, in books often written by writers who were themselves from the working classes. It also crested a fin de siècle wave of changes in 19th-century life that would go on to be made particularly visible by the first world war.

Victorian ‘ecologies of paper’

In part, though, the failure of Gissing’s early novels may be traced to not only a crowded market of new writers, but what Richard Menke calls a crowded “ecology of paper”.[13]

In 1887, a boom in Spanish esparto grass crops and wood fibre caused a ripple effect through the British paper production and publishing industries, with more books commissioned, bought and printed than ever before. On top of increased literacy rates, this meant that, for the first time in history, the working classes comprised a significant portion of the reading public, opening up changing literary tastes – and, especially, an appetite for novels that accessed everyday experiences beyond those of the upper- and middle-classes.

This unique set of circumstances helped to make Victorian London a publishing metropolis that seriously challenged Oxford and Cambridge, whose businesses were founded on their knowledge economies, Clive Hill argues.[14] Disparaging critical attitudes towards such “middlebrow” publishing, to which Gissing’s New Grub Street belonged, were born in part from the “complicated and deeply contested process [of] democratisation of social and political life in 19th-century Britain”.

Reviews and popular/critical reception

On 2 May 1891, the Saturday Review featured an unsigned review of New Grub Street that took issue with Gissing’s portrait of literary London: “The entire population does not consist of worthy ‘realistic’ novelists, underpaid and overworked on one side, and of meanly selfish and treacherous, but successful, hacks on the other”.[15] However, less than a week later, another reviewer in the same publication praised Gissing’s “instinct with life” and “picture, cruelly precise in every detail, of this commercial age”. (We might be reminded here of Milvain’s side hustle ghostwriting reviews.)

Other reviews in the Whitehall Review, the Athenæum, and the Author throughout the 1890s all lauded the novel’s expert realism, indicating Gissing’s position at the head of this emergent style of writing. Over the course of his career, Gissing’s novels were reviewed in such periodicals as the Illustrated London News, the Spectator and more. Taking the Illustrated London News as representative to give an indication of Gissing’s readership: at its peak in the late 19th century, the magazine enjoyed a circulation of around 300,000, overwhelmingly made up of the middle classes.[16] Can we consider these reviews to be engaging with class issues in a meaningful way, then, or are the reviewers again writing from a middle-class perspective in considering the “realism” of Gissing’s fiction?

Gissing and realism

We might think of earlier realist novels like [George Eliot](https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-companion-to-george-eliot/introduction-george-eliot-and-the-art-of-realism/A2B3A79E33C8712CE74AE7C4F6249947#:~:text=Eliot's realism extends from the,aspect of her realist project.)’s The Mill on the Floss (1860) as a precedent for Gissing’s work, but the class structures that are made explicit in New Grub Street should not be glossed over. While Eliot was also concerned with the inequities of Victorian society, Maggie Tulliver is a squarely middle-class construction, as are the pastoral environs of St Ogg’s. Likewise, Eliot’s work has a relationship with Wordsworth’s aesthetic philosophy in the figuring of rural working-class communities and characters as part of an integrated whole, corresponding to paternalistic attitudes around lack of accessible education and intellectual “purity”. As Raymond Williams demonstrates in Culture and Society: 1780-1950 (1965), Eliot and other writers like her sought to deny the importance of the power of social class in people’s identities.

What did Gissing himself make of this endeavour? In an 1895 letter to Thomas Hardy, he wrote, “As for work, I am writing a lot of scrappy things, to be called ‘Human Odds & Ends,’ for the Sketch [a British illustrated weekly journal] – blotched impressions of miserable, squalid lives. They are not worth much, but such work must needs be done, & [his editor, Clement] Shorter tells me that this kind of thing extends one’s public.”[17]

In an earlier letter to his publishers, on 8 February 1887, Gissing had expressed his disappointment at their £50 offer for his latest title, Thyrza, and suggested that the book might benefit from being published with a list of his previous titles: “My signed work has got for itself a certain recognition, which should certainly increase the market value of what I now write.” The sum of £50 in 1887 is equivalent to about £8,200 today – in line with current mid-tier fiction title advances, which are usually in the £5,000 to £10,000 range – indicating how little 137 years has moved the needle in terms of author advance payments.[18]

In a European context, Gissing’s work tapped into a genre of social realism that was already popular across France and Italy. In Italy, particularly, the literary genre of verismo had first been described by Luigi Capuana in 1872. Gissing met his third wife Gabrielle Fleury after she wrote to him requesting to translate his work into French, indicating an appetite for social realism on the continent. (We might even wonder to what extent Gissing came into contact with this genre during his 1888 Italy trip, although it is difficult to get a sense of this from his letters from the time.)

However, in rigidly sticking to the antiquated system of publishing favoured by Smith, Elder – in which Gissing dealt directly with his editor, who bought his entire copyright for a fixed rate – it appears that Gissing himself benefited little from the social realism moment in Europe beyond its minor ripple effect on the British market. Perhaps the instinct of Harold Biffen, New Grub Street’s realist writer character, was right: he may indeed have been better off had he tried to publish his novel The Grocer into Europe’s rather more fertile social realist literary market, instead of London’s.

The afterlives of New Grub Street

There have been few adaptations of New Grub Street. In 1972, 2002, and 2016, the novel was adapted as separate radio plays, all for BBC Radio 4. There are reports of an iPad videogame series developed by Elizabeth Chang and Nathan Boyer, Adventures of a Hack, based loosely on the infrastructure of the novel. And in 2005, Christopher Douglas created the comedy radio series Ed Reardon’s Week, which transposed the novel’s themes and certain characters to a contemporary setting. More recently, in January 2024, Gissing himself was the subject of a Spectator character study by DJ Taylor.

It’s interesting to ask, as we do in the podcast: what is it about New Grub Street that makes it so importable to a radio form, as opposed to TV or film? The obvious conclusion would be the lack of a happy ending – or rather its long and very unhappy one.

After Gissing’s death, HG Wells hailed him as “the master and leader of the English realistic school”, to whom later realist writers ought to feel indebted. Gissing’s work also had a profound influence on George Orwell who, in a 1948 essay on Gissing, wrote that “England has produced very few better novelists”.

In the essay, Orwell used Gissing to exemplify his construction of “the novel” more broadly, as “a story which attempts to describe credible human beings, and – without necessarily using the technique of naturalism – to show them acting on everyday motives and not merely undergoing strings of improbable adventures. A true novel, sticking to this definition, will also contain at least two characters, probably more, who are described from the inside and on the same level of probability – which, in effect, rules out the novels written in the first person.” Likewise, Orwell’s analysis of the formal qualities of Gissing’s style (“certainly there is not much of what is usually called beauty, not much lyricism, in the situations and characters that he chooses to imagine, and still less in the texture of his writing”) make visible a throughline with his earlier 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language.

Interestingly, Orwell also notes that he has “never been able to get hold of” any of Gissing’s works beyond New Grub Street_,_ Demos and The Odd Women_,_ gesturing towards the strangely patchy availability of Gissing’s oeuvre in the 20th century. The increase in the availability of his works, together with his growing profile in literary studies, suggests that in the 21st century, contemporary readers are finding new relevance in Gissing’s work.

Notes for researchers

Gissing’s copyright appears to have lapsed and he appears not to have a designated estate, though there is a Gissing Trust dedicated to the upkeep of his childhood home. His archives include one collection housed by the University of Manchester (comprising 180 printed items and 384 archive items, ie manuscript material, including an extract from his boyhood diary, and candid letters to his sister, Ellen), and two other collections currently maintained in the US: the Yale George Gissing collection (comprising ten boxes and one portfolio of letters, manuscripts, publisher agreements, school certificates and photographs), and the New York Public Library George Gissing collection of papers (comprising 1,108 items in both French and English, described as manuscripts, correspondence, diaries from 1879-1913, a commonplace book, financial and legal documents, pictorial material, and flora).

Further reading

In addition to the footnotes, the below articles may of particular interest:

Circulating Libraries in the Victorian Era by Troy J Bassett (Oxford Research Encyclopedias, 2017)

Bassett breaks down the structural and commercial functions of the Victorian lending libraries, drawing comparisons to modern-day retailers like Amazon

George Gissing’s Ambivalent Realism by Aaron Matz (Nineteenth-Century Literature, vol 59, no 2, 2004)

Here, Matz pulls out key reviews and responses to the Victorian realist literary movement to inform understanding of the critical reception of Gissing’s work

The Reception of George Gissing in China by Ying Ying (English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol 58, no 2, 2015)

Ying considers the reception of Gissing’s work in a Chinese context, with an emphasis on culturally specific labour relations, and maps the evolution of “Gissing studies” in the 20th century. Also places a particular emphasis on the train in New Grub Street as a meaningful juxtaposition of “aesthetic value with thematic significance” for Chinese scholars

A History of British Publishing by John Feather (Routledge, 2006)

A comprehensive and accessible history of publishing in the UK, designed as a primer for students on creative industry placements and courses. Tours through the development of the industry from its early modern origins to the 21st century, and locates the British publishing industry within the context of competing disciplines like education, politics and technology

George Gissing_, London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: The Diary of George Gissing, Novelist_, ed. Pierre Coustillas (Harvester Press, 1978). ↩︎

Gerald Hull, “George Gissing, New Grub Street and the Writer’s Inner World: Relevance and Disaster” (essay, University of Wales, Bangor, 2018). Accessed 10 June, 2024, https://www.brlsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/George-Gissing-essay-Feb-2018.pdf. ↩︎

D Duhaime, “The Statute of Anne and the Geography of English Printing” in Copyright and the Early English Book Market: An Algorithmic Study. Accessed 18 June, 2024, https://earlybookmarket.com/printing-geography.html#:~:text=After the 1662 Licensing Act,at a fairly steady rate. ↩︎

“Industries: Printing” in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont With Hatton, Feltham, Hampton With Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton (1911). Accessed 19 June, 2024, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol2/pp197-200. ↩︎

Bob Clarke, From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899 (Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2004). ↩︎

“Grub Street, N.” Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2023). ↩︎

Ian Rock, “How to Repair Your Victorian Roof” in Real Homes (2019). Accessed 26 June, 2024, https://www.realhomes.com/advice/how-to-repair-your-victorian-roof. ↩︎

Arthur L Bowley, Wages in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century: Notes for the Use of Students of Social and Economic Questions (CJ Clay & Sons, 1900). ↩︎

Guinevere L Griest. Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel (Indiana University Press, 1970). ↩︎

George Gissing, New Grub Street (Smith, Elder & Co, 1891). Accessed 3 June, 2024, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1709/pg1709-images.html ↩︎

Frederick Nesta, George Gissing, Grub Street, and The Transformation of British Publishing (Edward Everett Root, 2020). ↩︎

Stephen Whiting, “Pox, Prose, and Prostitution: Masculine Anxiety, the Myth of the Male Author, and the Late-Victorian ‘Exchange Economy’ in George Gissing’s New Grub Street,” Journal of Victorian Culture 27, no. 4 (2022). ↩︎

Richard Menke, “New Grub Street’s Ecologies of Paper,” Victorian Studies 61, no.1 (2018). ↩︎

Clive E Hill, “Gissing’s New Grub Street and The Origins of Middlebrow Publishing,” Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London 9, no. 1 (2011). ↩︎

Aaron Matz, “George Gissing’s Ambivalent Realism,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 59, no. 2 (2004) pp212-248. ↩︎

The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003. Accessed 27 June 2024, https://www.gale.com/c/illustrated-london-news-historical-archive. ↩︎

Pierre Coustillas, “Some Unpublished Letters from Gissing to Hardy,” English Literature in Translation, 1880-1920 9, no. 4 (1966). ↩︎

Andrew Franklin, “The profits from publishing: a publisher’s perspective,” The Bookseller (2 March, 2018). Accessed 1 July, 2024, https://www.thebookseller.com/comment/the-profits-from-publishing-a-publishers-perspective. ↩︎

Georgia Poplett is a researcher who worked with The Bee and New Writing North as part of a placement supported by the Northern Bridge Consortium, a Doctoral Training Partnership funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments