Hilary Mantel’s childhood: on the side of the hard sums

Hilary Mantel was born Hilary Mary Thompson on 6 July 1952 and raised in the mill village of Hadfield, Derbyshire. She was the oldest of three children. Her father was a clerk and her mother a school secretary. The family was Roman Catholic, though Mantel would later describe herself as lapsed from the age of 12. Her great-grandparents were millworkers in County Waterford in Ireland before they moved to Derbyshire.

Mantel experienced recurring bouts of ill health in childhood and was nicknamed “Little Miss Neverwell” by one of many doctors who would fail to diagnose or treat her properly. When she was seven, her mother’s lover, engineer Jack Mantel, moved in with the family; Mantel’s father slept in another bedroom for four years until the family moved to Cheshire without him. Mantel did not see her father again and took her stepfather’s surname.

In an interview the day after winning her first Booker prize, for Wolf Hall in 2009, Mantel recalled her school experience “in a classroom [with] two different blackboards, one with hard sums and one with easy sums. And all the children with holes in their jerseys were on the side with the easy sums. They had been written off already […] I was on the side of the hard sums.”

In 1970, aged 18, Mantel began studying law at the London School of Economics but after her first year transferred to Sheffield University, where she met fellow student Gerald McEwen. They married at the end of their second year, divorced in 1981, before remarrying in 1982. Mantel would later define her reasons for studying law as influenced by a desire for “a good career […] we had an inspiring teacher for criminal law, Professor Wood, who had a dry sense of humour and who was kind to me. I didn’t know, when I chose law, that my health problems would escalate and that I wouldn’t be able to have a career of that kind. The university looked after me when my health broke down.” While at Sheffield, Mantel identified as a socialist and was a member of the Young Communist League.

Her first books, and worsening health

After graduating in 1973, Mantel worked as a social worker and then as a shop assistant for Kendals department store in Manchester, during which time she began work on her first novel. (Completed in 1979, the book was rejected by agents and publishers and eventually published as A Place of Greater Safety in 1992.) In her twenties, Mantel’s health worsened, and she was wrongly diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. The antipsychotic medication she was prescribed only produced an experience of psychosis, destroying Mantel’s trust in medical professionals for a significant period of time.

Before four difficult years spent in Saudi Arabia (which would inspire her third novel, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street), Mantel lived with her husband in Botswana, where he worked as a geologist, from 1977-1982. In 1979, her discovery of endometriosis in a medical textbook led to her having a hysterectomy at the age of 27. Mantel directly traced her illness to her reliance on writing as the only form of livelihood which her physical abilities allowed. Nonetheless, she later said, “it didn’t do me any good, diagnosing myself. It didn’t speed things up. It just made doctors think I was arrogant.”

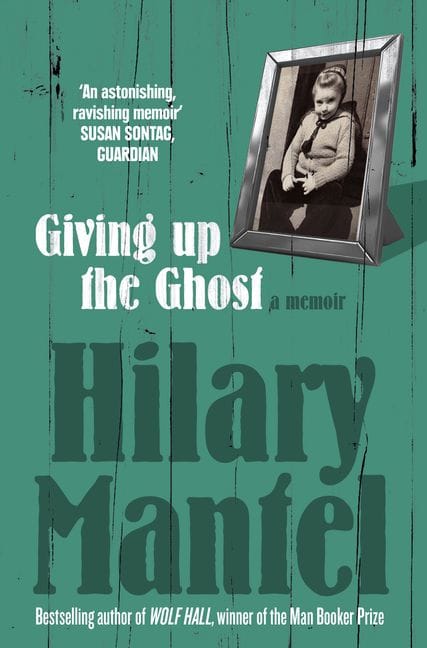

In 1985, Mantel’s first novel, Every Day is Mother’s Day, was published by Chatto & Windus to moderate critical acclaim. It was followed by a sequel, Vacant Possession, in 1986 (Chatto & Windus) and further novels Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (Viking, 1988); Fludd (Viking, 1989); A Place of Greater Safety (Viking, 1992); A Change of Climate (Viking, 1994); An Experiment in Love (Viking, 1995); The Giant, O’Brien (Fourth Estate, 1998); and Beyond Black (Fourth Estate, 2005). In 2003, Fourth Estate published a memoir, Giving Up the Ghost, and Learning to Talk, a collection of short stories. Mantel’s change of publisher came amid the tumultuous publishing landscape of the 1980s and 1990s, in which Penguin rose through multiple rapid acquisitions to become a titan of the market; the company acquired Chatto & Windus and made it an imprint in 1987. Mantel’s list then moved to Penguin’s Viking imprint, where it remained until 1998, when she signed with Fourth Estate, an independent publisher acquired by HarperCollins in 2000. Her backlist was reissued and rejacketed by Fourth Estate in 2010 in the wake of her Booker win, as is standard practice within the publishing industry.

The staggering success of Wolf Hall (Fourth Estate, 2009) brought Mantel attention beyond the confines of so-called midlist fiction. Wolf Hall and its sequel, Bringing Up the Bodies (Fourth Estate, 2012), each won the Booker prize in their year of publication. (Mantel was only the fourth author and first woman to win the Booker more than once.) In 2020, the final title in the “Wolf Hall trilogy”, The Mirror and the Light, was longlisted for the Booker. In addition to the novels, Mantel was a prolific short-story writer – the 2014 collection The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher includes the story of the same year from which the book takes its title – critic and essayist, delivering the 2017 BBC Reith Lectures on the role of history in culture. As of March 2025, her published works include: 12 novels; two short story collections; a memoir; a collection of her articles from, and correspondence with, the London Review of Books, Mantel Pieces (Fourth Estate, 2020); and A Memoir of My Former Self (John Murray, 2023) an posthumous anthology of autobiographical writings. Following complications arising after a stroke, Hilary Mantel died aged 70, on 22 September, 2022 – the day before her 50th wedding anniversary, and four days before a long-awaited move from her home in Devon to Ireland.

(Not) Giving Up the Ghost

Giving Up the Ghost was Mantel’s ninth book and first memoir, published into the tailwind of such commercial literary memoirs as Jung Chang’s Wild Swans (1991), Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club (1995), Gore Vidal’s Palimpsest (1995), Martin Amis’s Experience (2000), and A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk (2001).

In a preface to a 2017 Slightly Foxed edition of the book, the biographer Maggie Fergusson wrote that “as [Mantel] reveals in a rapid-fire interview at the end of my battered paperback, [Giving Up The Ghost] was originally intended as a purely private exercise, like her diaries, only to be read by others after her death. What made her change her mind she doesn’t say.”

Christopher Potter, author and managing director of the publishing house Europa Editions UK, was a publisher at Fourth Estate who played a key role in persuading Mantel to move there from Penguin. According to Potter, she had been commissioned to write a novel, but was struggling with writer’s block. Potter suggested that she produce a book of short stories to buy her extra time to write the novel. Mantel duly produced a sheaf of stories, which struck Potter as significantly autobiographical; this was confirmed by Mantel, who indicated that she had resisted publishing them before as she did not want her mother to read them. (However, she did agree to publish a selection in the LRB, a publication that her mother did not read.)

Potter suggested she write an introduction to harness the stories together. This ended up being 35,000 words and became the bedrock for two of her books: Giving Up the Ghost and the Learning to Talk short story collection. He then again suggested she write a memoir, since her mother’s health was ailing, and she agreed. Mantel was apparently very keen on the idea of publishing in different genres while she worked her way through her writer’s block – these two interim titles proved instrumental in dissipating the block, causing her to begin work in earnest on what would later become Beyond Black.

Potter agreed that Mantel was unusually tuned into the needs of the market and recognised her writing as her economic livelihood as well as her art. I asked whether he ever received pushback acquiring new titles from Mantel during the years in which she only sold modestly; he reflected that before Fourth Estate was acquired by HarperCollins, he held a significant amount of editorial sway in acquisitions meetings despite the fact that Mantel’s books “never sold” or were shortlisted for prizes. This situation changed after the company was sold (although Mantel fortunately sold well enough to justify future advances by then).

He said that it was “a great mystery” to him as to why Mantel didn’t break out sooner than she did. He had tipped The Giant, O’Brien as her “big break”, but it was not longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction that year (1998) because, according to Potter, Fourth Estate submitted another book, Larry’s Party by Carol Shields, the eventual winner. Potter did not give figures, but did mention that what Fourth Estate paid for Mantel’s novels did not necessarily reflect her success in the market at that time.

Potter added that Mantel didn’t speak much to him about her class identity, as their conversations usually circled around the mystery of life, dark forces, evil and science. (Oh, to be a fly on those walls!) He added that they did not come from similar backgrounds, which may have been a reason why she did not discuss hers with him.

In Mantel’s own words, spoken the morning after winning the Booker for the first time, “You know it is going to change your career. It may not change your writing, but your career is a different thing.” In the same interview, Mantel noted that “writing [Giving Up the Ghost] was a freeing process in some ways. Although I’ve still got a lot of problems with my health, things have improved. And I think the memoir was saying, ‘Well, that was my past.’ And hanging on to the hope that things would be better. You see, I think what a book like [Wolf Hall] needs is a huge amount of energy, and physical and mental energy feed off one another. And I don’t think I could have done it when I was really ill. The writing of Beyond Black, my last novel, took me a long time. I had a gruelling few years and it held the book back. And then we began to climb up the other side, and I thought that I probably did have the energy to tackle it. It’s all about your internal economy, in a way. How much can you afford to spend?”

Giving Up the Ghost was reviewed in The Guardian, The New York Times, Publishers Weekly and Kirkus Reviews, and excerpted in the London Review of Books. This clutch is notable for its appeal to a middle-class-and-above readership, despite Mantell’s working-class roots, which were largely glossed over by reviewers. In an interview with The Guardian in May 2003, Giving Up the Ghost was explicitly positioned as a health memoir, in which Mantel is said to offer “the account of a life haunted by illness and medical incompetence, written in words that never fail her.” (The interviewer finds another interplay between health and Mantel’s life, noting that the author is then living in “a former lunatic asylum […] now a carpeted oasis she shares with her husband, Gerald.”)

Strikingly, there are traces of pathologised ambition in the text which may resonate with the class tensions at play. After she began experiencing the symptoms of endometriosis aged 19, Mantel “was sent to a psychiatrist who diagnosed overambition.” Certainly there are gendered power relations at work here, too, but as Mantel herself said, “I was seethingly ambitious, I don’t make any secret of that. I needed to be somebody. The only way I could think of was by writing. Because all you need is paper and pencil and you can do it horizontal. […] It was the cheapest source of power. Words are free.”

In diary excerpts published in the London Review of Books in November 2010, issued a month later as a UK-only ebook, Ink in the Blood: A Hospital Diary, Mantel writes scathingly on Virginia Woolf’s complaints about the “poverty of the language” used to describe illness: “What of the whole vocabulary of singing aches, of spasms, of strictures and cramps; the gouging pain, the drilling pain, the pricking and pinching, the throbbing, burning, stinging, smarting, flaying? All good words. All old words. No one’s pain is so special that the devil’s dictionary of anguish has not anticipated it. […] No doubt language fails in that shuttered room called melancholia, where the floor is plush and the windowless walls are draped in black velvet […] But then, mental suffering is so genteel; at least, until the dribbling sets in. Virginia only has decorous illnesses. She has faints and palpitations, fevers and headaches […] Virginia never oozes. Her secretions are ladylike: tears, not bile. She may as well not have had bowels, for all the evidence of them in her book.”

Anything with a white cover and sad face: the rise and fall of “misery memoirs”

For Mantel, both language and the body appear to exist materially under the conditions of social class. Although these clues to Mantel’s socioeconomic backstory appear as essential stitches within the fabric of Giving Up the Ghost – “Persiflage is my nom de guerre. (Don’t use foreign expressions; it’s elitist […] And as for transparency – window panes undressed are a sign of poverty, aren’t they?” – her class background was largely redacted in the publication and marketing of Giving Up the Ghost. Indeed, I noticed a general pattern that external comments on Mantel’s working-class identity were framed in terms of a necessary hardship to produce the genius of her work. This sense was pervasive in both publisher copy and in reviews.

Perhaps the most famous (or infamous, as the case may be) memoir of this period was Angela’s Ashes (1996) by Frank McCourt, which enjoyed resounding critical acclaim and commercial success and significantly boosted the popularity of “misery lit” – and in particular “misery memoirs” – into the book charts. However, controversy surrounding accusations of inauthenticity were repeated with later works, such as James Frey’s now-discredited A Million Little Pieces (2003). A series of such scandals helped slow the rate of production of books of this type until it dropped off almost entirely in the latter half of 2008 (interestingly, coinciding with the global financial crash, perhaps creating a literary landscape in which the misery memoir resonated too powerfully for many readers). In December 2008, HarperCollins publisher Carole Tonkinson told The Guardian that there had been “a lot of over-publishing and publishing of stories that weren’t as good or well-written, and there have been a lot of problems legally with some of them […] We are cutting back a bit.”

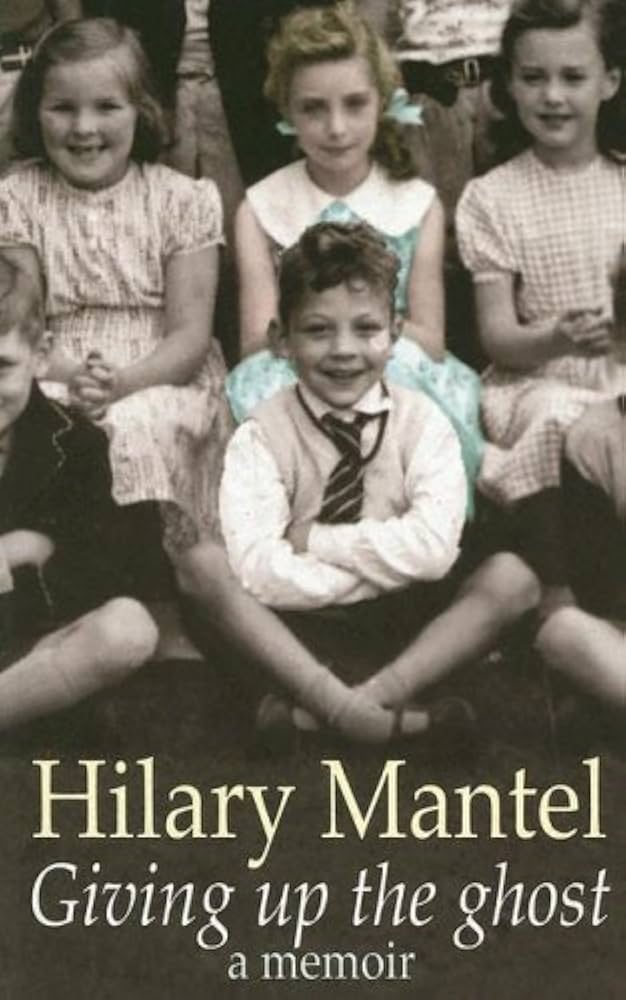

Giving Up the Ghost’s place in this sub-genre is signified by the hardback’s cover design and jacket. The back copy includes endorsements (all female, interestingly) from noted memoirists Rachel Cusk and Margaret Forster, along with the novelists Helen Dunmore, Clare Boylan and Carol Shields. In another quote on the front cover, Cusk likens the novel to Lorna Sage’s Bad Blood (2000), a memoir of working-class adolescence in Wales; Kathryn Hughes, in her introduction to a tenth anniversary edition of Bad Blood, roundly rejects the idea that the book is a misery memoir.

Mantel’s memoir has had a range of cover designs and jackets.

It is interesting that other than the reappearance of a teal colourway across several designs, the covers are not bound together by a certain set of images in the way that one might expect. In publishing today, there is a tendency to retain original cover designs with alternate colourways; the afterlives of Mantel’s memoir are a striking departure from this. Likewise, as the book moves beyond the late 90s/early 2000s memoir boom, the cover quotes shift from almost exclusively other memoirists in vogue, to more critical platforms such as The Guardian, with taglines emphasising Mantel’s Booker wins. We might say that the marketing strategy moves beyond memoir with a capital M and into Mantel with a capital M – but what was lost in the process? Was there an erosion of Mantel’s working-class origins and identity in the rush to claim or qualify her as a product of an increasingly middle-class Britain under Blair’s government?

These covers acquire a particular significance in proximity to contemporaneous memoirs, especially those overtly coded as middle- or working-class. Though it is not a hard and fast rule across the board (Martin Amis’s Experience sported a similar cover), books marketed as misery memoirs predominantly had covers with titles in cursive fonts and black-and-white photographs of children, signalling formative experiences of abuse and/or hardship, frequently involving poverty. There may also be a point to be made here about Amis’s publishers costuming him in the guise of the working-class misery memoir to appeal to the same demographic, despite his privileged upbringing.

The packaging of books in this way is seen more recently in the trend of the “shopping trolley” memoir – see for example Dr Jessica Taylor’s Underclass (2024) and Cash Carraway’s Skint Estate (2019). However, interestingly, this schema has also been adapted for political nonfiction – Paul Embery’s Despised (2020), Darren McGarvey’s Poverty Safari (2017), and Danny Dorling’s Shattered Nation (2023).

A contrasting, emerging cover trend in the last decade has been the use of bright colourways layered on top of vintage personal photos, again with common usage of teal. From white covers with sad faces we seem to have moved towards blue-and-red covers with happy faces – but I would argue that this does not occlude troubling “misery lit” narratives beneath the surface. The most cursory of Google searches produces an array of red-and-teal colourway covers belonging to the “medical nonfiction” genre, an immensely popular genre today. Are there disturbing suggestions at play here to do with “pathologising” being working class? This comes with a suggestion that the working-class memoir is only worth reading once the author has got better/bettered themselves. This may be far too speculative – but the unexpected cover design dialogue between these two genres seems significant.

“Most of us spend our lives in adaptation”: Mantel on stage and screen

Though Giving Up the Ghost, A Hospital Diary and Ink in the Blood: A Memoir of My Former Self have not been adapted into another medium, her historical novels have been phenomenally successful in this regard. In her final Reith Lecture, Mantel spoke at length about the snags and troublespots of adaptation: “Fiction, if well written, doesn’t betray history, but opens up its essential nature to inspection. When fiction is turned into theatre, or into a film or TV, the same applies: there is no necessary treason […] Indeed, the work of adaptation is happening every day; without it, we couldn’t understand the past at all. An event occurs once: everything else is reiteration, a performance […] Most of us spend our lives in adaptation, aware we have a secret self, and aware that it won’t do. We send out a persona to represent us, to deal for us in public; there are two of us, one home and one away, one original and one adapted.”

Mantel herself adapted The Giant, O’Brien into a BBC Radio 3 play broadcast in December 2002. The Oscar-winning screenwriter Peter Straughn adapted the first two novels in the Wolf Hall trilogy for a six-part TV miniseries, Wolf Hall, starring Mark Rylance, Damien Lewis, and Claire Foy, first shown on BBC Two in 2015. The third book, The Mirror and the Light, was made into a six-episode series of its own, also written by Straughan for the BBC, broadcast in 2024. Similarly, the Royal Shakespeare Company staged Wolf Hall Parts One & Two in 2013, adapted by Mike Poulton, and The Mirror and Light premiered in 2021, adapted by Mantel and Ben Miles (who played Thomas Cromwell in all three theatrical productions).

Surveying her work in all its variety and diversity of form prompts the question: did any common threads in her writing bring the success she sought? After her first Booker win, Mantel was asked whether she identified with the opening scene in Wolf Hall, in which Cromwell, as a child, is viciously beaten by his father. The interviewer wondered whether that particular scene revealed “any hint of being nicknamed ‘Neverwell’”.

Mantel replied: “This has not happened to me. But I know about oppression. I know about oppression within the family […] And when you notice something like that in childhood, [the memories of oppression] drive through your life. You’ve always got an eye out for underdogs.”

Georgia Poplett is a researcher who worked with The Bee and New Writing North as part of a placement supported by the Northern Bridge Consortium, a Doctoral Training Partnership funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments