A Biography of Frank McCourt

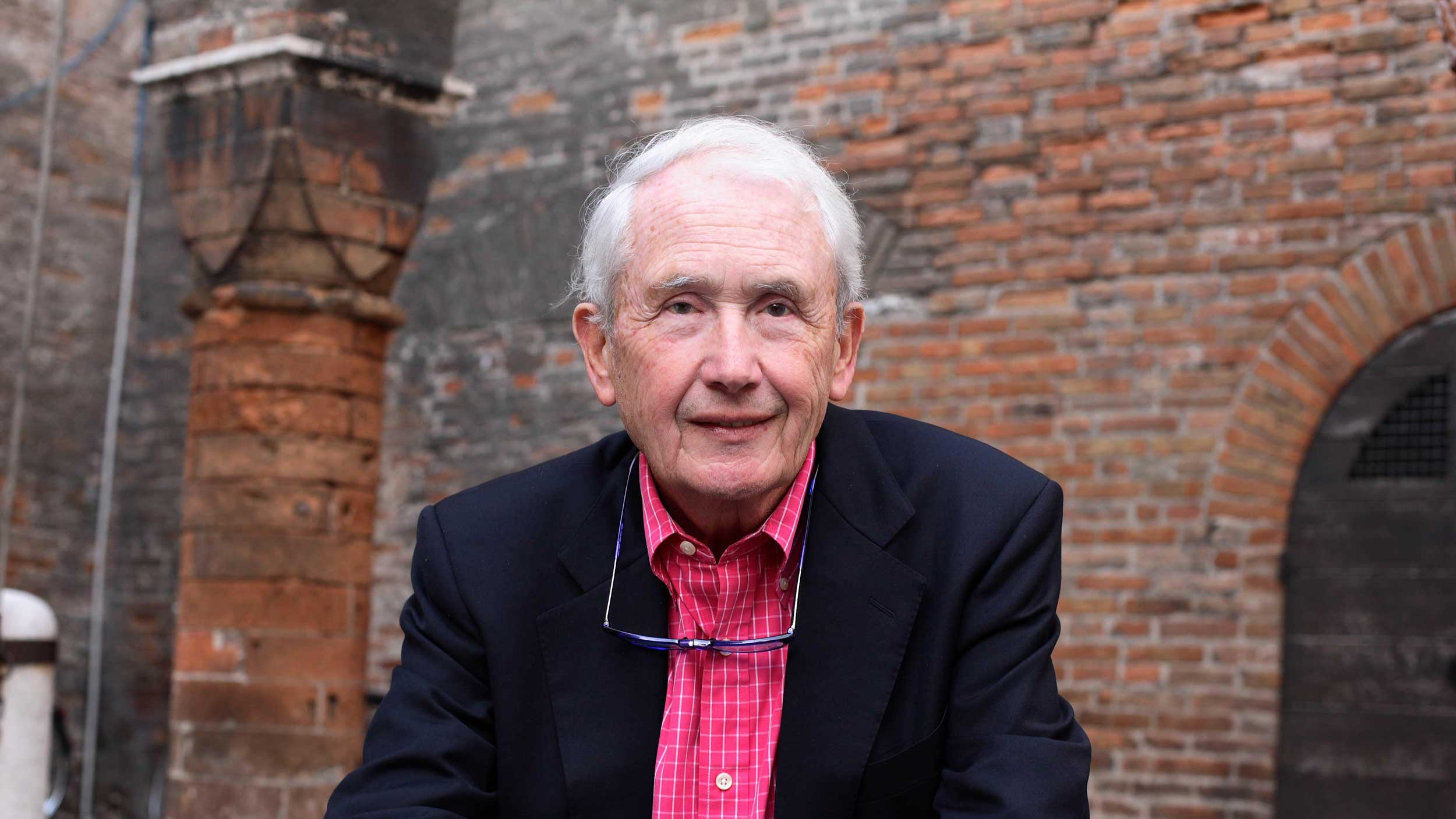

Frank McCourt was born in 1930 in New York and died in 2009, also in New York. However, his memoir Angela’s Ashes recounts his childhood in Limerick, Ireland. His parents, Angela and Malachy Sr, had both moved to New York from Ireland and met there shortly before his birth. Angela’s Ashes recounts the encounter that led to Frank’s conception, although the veracity of this account has been questioned, with one critic suggesting that Angela may have been sent to New York after she became pregnant by a married man in Limerick.

Angela had five children in New York: Frank, Malachy, twins Eugene and Oliver, and a daughter, Margaret. After Margaret died when Frank was four, the family returned to Limerick, where the twins also died, but two more brothers, Michael and Alphie, survived to adulthood with Frank and Malachy.

McCourt’s father, Malachy Sr was an alcoholic, mostly unemployed, and allegedly involved with criminal gangs in both New York and Ireland. Again and again in the memoir, McCourt describes his father returning home drunk and dragging his sons out of bed to make them promise to die for Ireland; he also describes how his father continually tells him stories, from Irish mythology, about their neighbours, about world news, and about Irish history. The family lived hand-to-mouth, relying on the dole (when Malachy Sr didn’t drink it), and charity from the St Vincent de Paul Society. Angela’s mother and sister also supported the family, and eventually they received government aid when Malachy Sr left for England and ceased any kind of support for the family. McCourt describes scavenging for coal dropped by wagons on the Dock Road, for fish and chips abandoned by drunk men, and for any kind of food at all when his mother fell sick and couldn’t care for the children.

As well as poverty, sickness was a continual presence in McCourt’s childhood. Apart from the deaths of his baby siblings, McCourt describes the deaths of multiple children from TB and diphtheria, and his own stint in hospital for typhoid and, later, conjunctivitis. Adults also die. A number of older men become mentor figures for Frank, only to be taken sick before he can really benefit from their guidance. One old man gives him a brief job reading A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift, an author the adult McCourt would describe as “one of my idols”.

By adulthood, Frank McCourt was desperate to return to New York, which he did at 19. His life there as a young man is recounted in his later memoirs, ’Tis and Teacher Man. He initially worked odd jobs before joining the US Army for the Korean war. On his return, he exploited the GI Bill to train as an English teacher, even though he had left school at 13. He taught at Peter Stuyvesant High School for most of his career, and started writing only on retirement in 1987. He had, however, written and performed a comedy show with his brother Malachy called A Couple of Blaguards, first produced in 1985, which used some of the material found in Angela’s Ashes. The brothers started developing this show in the 1970s, initially for family and friends.

McCourt considered writing the memoir as a cathartic experience which allowed him to get “a lot of the stuff out of my system”. Although he had wanted to write most of his life, and his daughter Margaret recalled that “long before Angela’s Ashes, I was aware of his writing ability, because he was always writing everywhere”. McCourt, however, felt that he lacked material, explaining many times that he had previously believed he didn’t have anything to write about, because no one wanted to hear about a family in a slum in Limerick. “We were worthless. Our concerns were irrelevant to the world,” he once said, ‘I would’ve been ashamed to write about the way I grew up.’ He was inspired by the autobiographies of the Irish playwright Sean O’Casey, which were ‘appealing because he grew up in a poor family’. This must have impacted him before retirement, because Margaret also recalls that in his teaching, McCourt told his students that ‘everyone has something to write about”.

McCourt’s Irish heritage may also have been a barrier. His brother Malachy, an actor, described in an interview how “when an Englishman speaks well, they say he’s eloquent. When an Irishman speaks well, they say ‘Ah you have the gift of the gab. Ah you kissed the Blarney stone.’ It’s always that pejorative about our use of the language.” Historical discrimination against the Irish, particularly through language policies, may also have impacted McCourt’s confidence in writing. As the McCourts were growing up in Ireland, the Irish government was heavily focused on reviving the Irish language after years of language discrimination under English rule. This included favourable treatment for Irish-speaking children, and arguably an undervaluing of those like the McCourts, who spoke English at home. In Angela’s Ashes, McCourt describes his teachers disparagingly labelling the McCourts as “Yanks”, while other residents of Limerick looked down on them because their father was from “the North” – that is English-favouring Northern Ireland.

Angela’s Ashes was a global best-seller, selling more than 10 million copies to date. It has been translated into more than 100 languages, and made into a film and a theatrical musical. McCourt wrote two sequels, ’Tis (1999) and Teacher Man (2005), which describe his adult life in the USA. Finally, in 2007, he wrote a children’s book called Angela and the Baby Jesus about his mother’s childhood, and this has been adapted into an animation called Angela’s Christmas. It was produced by his wife, Ellen McCourt.

Frank McCourt’s Limerick

McCourt grew up in the slums known as the “lanes” of Limerick. He describes living on three lanes in his memoir: Windmill Street, Hartsonge Street, and Roden Lane, before the family was taken in by relatives following the departure of his father. Robinson describes these lanes as being “not slums apart, but a working-class neighbourhood in-between”. The map below shows this with the closely packed houses of the lanes surrounded by more gentrified areas.

The lanes have been redeveloped since McCourt’s childhood, when they lacked internal plumbing. Malachy McCourt describes being impressed by the “prosperity” in evidence on a visit in the 2010s, with people seeming less desperate to leave, and the river Shannon apparently a less threatening presence than in his childhood, when it was, in the words of Malachy Sr in Angela’s Ashes, “a river that kills”. The film of Angela’s Ashes had to use locations in Cork to film scenes from the lanes because there were none suitable left in Limerick; this can be disappointing for literary tourists who, as the Angela’s Ashes walking tour guide Michael O’Donnell has said, “want to see the Limerick from Angela’s Ashes”. Locals, he added, are proud that that Limerick now “doesn’t exist”.

Publication and critical reception

McCourt’s route to publication, as he writes in his acknowledgements, was smoothed by an “exaltation of women” who helped him find an agent and publisher. McCourt had a friend called Mary Breasted Smyth, who was a journalist and had a couple of books published. When she asked him at a party if he was “working on anything”, he shared the manuscript of Angela’s Ashes with her, and on reading it, she told him it was a “work of lyric and comic genius”. Mary’s poor experience trying to sell her own books to publishers through her agent, who had been told that “Irish books don’t sell”, meant she turned instead to another friend, literary agent Molly Friedrich. Molly, who had just suffered a bereavement, was initially unenthusiastic, looking on this ‘memoir by an unknown writer set in Ireland in the 1930s’ without much hope. As soon as she got around to reading it, though, she “went wild”, and took it on in its unfinished state. Nan Graham, editor-in-chief at Scribner, published the memoir in the US on 5 September 1996.

The memoir was initially published in the UK by HarperCollins. The UK cover featured a class photo from McCourt’s school days in the top left corner, which caused controversy at a reading when one of McCourt’s schoolmates asked whether the author could identify him in the photo. McCourt could not and the schoolmate ripped up the book in response. It is noticeable that the 1997 Flamingo cover, an Australian imprint of HarperCollins, removed the class photo, replacing it with the photo of a little boy from the Scribner cover.

On publication, Angela’s Ashes was in general very well received. Kakutani wrote in the New York Times that “McCourt does for the town of Limerick what the young Joyce did for Dublin”. Angela’s Ashes received a variety of prizes, including a Pulitzer Prize (1997) and National Book Critics Circle Award (1996). It remained on the New York Times bestseller list for more than two years. The report for the Pulitzer Prize describes it as “a glorious book that bears all the marks of a classic”.

Early translations of the memoir continue to use the photo from Scribner on their covers, apart from a 1998 Czech edition, which interestingly used a contemporary photo of Frank and Malachy McCourt. The Czech blurb called the memoir “an aging man’s memories of his childhood”, highlighting the role of the author, Frank McCourt, which is elided through the child narrator in the memoir itself. The German edition also continued to use the original photo of a boy from the Scribner edition, but edited the subtitle of the novel to read “An Irish Memoir”.

With the production of the Angela’s Ashes film in 1999, a still from the movie showing young Frank looking grumpy became the most common cover image and has become the visual most associated with the book.

Angela’s Ashes and Misery Memoir

Angela’s Ashes has been seen as belonging to a genre of childhood autobiographies known as misery memoir. Alongside Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club and James McBride’s The Color of Water, Angela’s Ashes has been considered responsible for the boom in this genre in the 1990s and 2000s. Douglas comments that “What is distinctive about this grouping is that each text [depicts] a lower-socio-economic experience of childhood and each depicts trauma. Each represents a rags-to-riches journey from a poor childhood and unconventional family life to adult success.” The critic Kate Douglas’ description of the memoirs as “rags-to-riches” tales highlights some of the controversy around these texts, as they portray working-class childhoods as traumatic experiences which the authors escape to more “successful” lives. Roger Ebert’s review of the film adaptation of Angela’s Ashes, published in 2000, states baldly that “There must have been thousands of childhoods more or less like Frank McCourt’s, and thousands of families with too many children, many of them dying young, while the father drank up dinner down at the pub and the mother threw herself on the mercy of the sniffy local charities. What made McCourt’s autobiography special was expressed somehow beneath the very words as he used them: These experiences, wretched as they were, were not wasted on a mere victim, but somehow shaped him into the man capable of writing a fine book about them.”

Applied within the confines of the cultural product, this may be fair. However, Ebert’s dismissal of “thousands” of working-class children as “mere victims” captures the problematic impact of “rags-to-riches” narratives on the portrayal of working-class lives. Aoileann Ní Éigeartaigh suggests that although Angela’s Ashes was instrumental in creating the genre of misery memoir, in doing so McCourt subsumed his own experiences in a ‘collective of “miserable Irish Catholic” childhoods’ and ‘surrenders control of his own memoir to what he implies are the prevailing expectations of the genre.’ Since the genre had not yet been formed or recognised when McCourt was writing, this is hard to justify, but it does indicate how awareness of the genre can now colour impressions of an author’s work.

Douglas highlights the problem of truth in these memoirs, an issue that was critical to the reception of Angela’s Ashes, especially in Limerick itself. This issue is closely related to the issue of genre. In the run-up to its publication, Angela’s Ashes was alternately identified as fiction and as autobiography; only by the time of publication did the book assume its final category of memoir. G Thomas Couser’s handbook Memoir: An Introduction opens the definition of memoir by emphasising that memoirs are non-fiction, depicting the “lives of real, not imagined, individuals’, but that they ‘often incorporate invented or enhanced material, and they often use novelistic techniques.” The decision to categorise Angela’s Ashes – in its subtitle, remember – as a memoir places it between fiction and non-fiction.

Ebert connects these techniques to the idea of verbal history, since “the stories so unforgettably told in his autobiography were honed over years and decades, at bars and around dinner tables and in the ears of friends.” Verbal history plays a strong role in the novel itself, with the young Frankie McCourt listening to his father’s tales of Irish mythology and stories about people on the Lanes, as well as the constant and contradictory retellings by neighbours, teachers and family of the atrocities committed by the English against the Irish. McCourt’s use of memoir demonstrates the power and flexibility of this written genre and allows it to depict a working-class upbringing using the oral tradition in writing. It is no mean feat. As the writer Kevin Barry has suggested, literary snobbery may mean that the global success of Angela’s Ashes somewhat obscures its literary achievement.

McCourt himself, incidentally, suggested that TV programmes like Oprah and Jerry Springer had more impact on the genre than his own memoir.

Studs Lonigan and Tenement Fiction

Tenement fiction is a genre associated with the late 19th and early 20th century and the growth of slums in England and America. It comprises fiction set in tenement housing. In the USA, it was particularly associated with New York and Chicago, and thus is relevant to the New York-born Frank McCourt. Writers, David M Fine argues, ‘sought to mirror in fiction what the social scientists, settlement workers and reform journalists were revealing about the new urban America.’ The stories are often narrated through the eyes of a middle-class observer. It may be tenement fiction to which Éigeartaigh is referring when she talks about the “prevailing expectations of the genre.”

Sabine Haenni believes that tenement fiction aimed to make the slums of New York and their immigrant communities more visible to the middle class, thus reducing fear of the working class. However, this is not necessarily to the benefit of the working class, since “urban agitation and pedestrian confusion – along with working people’s point of view – are held at a distance so that the spectator can feel somewhat disembodied, not part of the scene.” Fine similarly argues that in tenement fiction, “poverty is rarely degrading; more often it is ennobling”, but this is because the characters are portrayed as innocents whose surroundings cannot blemish their purity. In this way, tenement fiction created a romanticised view of poverty that, while not inspiring pity and horror as in Victorian slum literature, instead inspired a voyeuristic interest in Bohemian lifestyles. McCourt himself criticises this when he describes middle-class writers who could afford to write while working low-paid jobs and who ‘affected poverty’ by slashing their jeans.

However, McCourt was nevertheless influenced by this genre. He described being introduced to Irish-American literature by James T Farrell’s Studs Lonigan, a book about Chicago’s slums and Irish-American Catholicism. Since tenement fiction was closely associated with the immigrant community in Chicago and New York at the turn of the 20th century, and Irish and Jewish immigrants formed a large part of that community, US tenement fiction is closely associated with these two ethnic identities and their interrelation in public perception. The interrelation can be found in many examples of tenement literature, including Studs Lonigan. It is interesting, then, that the only neighbour mentioned in the New York section of Angela’s Ashes is the Jewish Mrs Leibowitz, since this may result from McCourt’s knowledge of the tropes of New York tenement fiction.

McCourt was also heavily influenced by the Irish playwright Sean O’Casey, whose plays about life in Dublin tenements he enjoyed when he heard them on his neighbour’s radio as a child.

It is also worth mentioning the Vaudeville tradition here. A Couple of Blaguards has been described as Vaudeville, and certainly reworks several old Vaudeville jokes. The show has many of the same scenes as the memoir, including, for example, Frankie’s first communion. Jennifer Mooney locates negative stereotypes of Irish-Americans in Vaudeville, including drunkenness and clumsiness, which results in loss of work, as well as being motivated by the American Dream (for men, while women who strayed from “their place” were portrayed negatively). Via the comic sketches in A Couple of Blaguards, these negative stereotypes about Irish men and women may have influenced McCourt’s portrayal of his mother and father in Angela’s Ashes.

Criticism of Angela’s Ashes

The techniques McCourt employs in the memoir have led to accusations of inauthenticity and untruthfulness. Some readers from Limerick considered that McCourt damaged the reputation of their hometown, producing a “highly distorted and inaccurate picture” of its inhabitants, including his own family and his mother in particular. McCourt himself was concerned about this, and Jones quotes him saying on a book tour: “It’s Limerick you worry about. Limerick is where the experts are.”

It was on that tour that one of McCourt’s former schoolmates ripped up his copy of Angela’s Ashes in front of its author, showing that McCourt’s anxiety was justified, even if Jones suggests that this “vulnerability to those charges that he had embroidered the truth” was a ‘weakness’ of McCourt’s. Hannan relates this to the particular challenges of writing as a person from a working-class background about a working-class place, cheaply suggesting that “since the lives of Limerick’s working class rarely make it to the international stage, it is not unreasonable for them to want to see themselves portrayed accurately and sensitively.”

This burden of representation stifles many working-class writers, and for a journalist to make this point feels very much like playing to the gallery rather than defending a writer’s freedom of expression. Hannan, a journalist who relies on interviews he has conducted with residents of Limerick for his material, considers that McCourt, as an underrepresented writer, has a heavy responsibility to portray his origins in a positive light to a world that is inclined to see them negatively. He does not interrogate the potential tension for McCourt between the “accurate” and the “sensitive” in his memoir.

This dissatisfaction with McCourt’s portrayal of Limerick led some to write counter-texts. Hannan, who himself wrote a 1997 novel in direct opposition to Angela’s Ashes, entitled Ashes: The Real Memoirs of Two Boys from the Limerick Lanes, describes how “Frank’s venomous writing gave license to the Limerick storytellers” who ‘showed up in droves for the fight’ and ‘distorted the facts, twisted the realities, bent the truth and were as liberal with the actualities as much as McCourt did.”

McCourt lost at least one friend through the fall-out from Angela’s Ashes. The actor Richard Harris, who grew up in Limerick and later reconnected with both Frank and Malachy McCourt in New York, “attacked” the author after reading Angela’s Ashes. Malachy McCourt retaliated on behalf of his brother Frank by portraying Harris negatively as “an upper-class ‘Limerick git’ in his own memoir A Monk Swimming, drawing further ire from Harris. It is noticeable how the McCourt siblings stuck together despite accusations against Frank from others; Margaret said that “one of the things [Angela’s Ashes] did was to bring our family closer together”. Nevertheless, it is not clear that Angela herself would have appreciated the memoir. When she attended one of their performances of A Couple of Blaguards, she stood up in the theatre and denounced it as “a pack of lies”.

Differences in Irish and American responses to Angela’s Ashes

McCourt walked a tightrope in presenting his working-class childhood to readers who consisted both of middle-class Americans with particular expectations of Irish working-class stories, and the Irish working-class people he grew up with. Some American commentators took the opposite view to Hannan and considered McCourt’s memoir to be a sanitised version of his upbringing. In her review of the film, Janet Maslin described how, for her, “McCourt summoned his anecdotes with indefatigable charm, no matter how dire the circumstances were, to the point where his autobiographical story became an exemplary pilgrim’s progress.” For Malcolm Jones, McCourt got the balance right, but only because he “sidesteps sentimentality with a litany of hardship that would make a cynic flinch”. For these readers, the grit and grime of his upbringing is the essential selling point of his memoir. In contrast to the offended Limerick readers, Maslin considers it to be underplayed.

For some critics, such as James B Mitchell, McCourt leans too heavily towards his American readers, since he presents his time in Limerick as a disastrous mistake on his parents’ part and the whole novel is directed toward his eventual return to America, where he will achieve the American dream of escaping his impoverished working-class background and become a teacher through his own hard work. “Whether intentionally or not,” argues Mitchell, “Angela’s Ashes often seems to confirm the picture of Ireland as a superstitious, unhygienic, narrow-minded backwater of Europe. In this way, the book provides contemporary Americans with the unspoken guilty pleasure of slumming in mid-twentieth-century Limerick without ever having to leave the comfort of their clean, well-plumbed country.”

The Classic of Irish-American Literature

Critics who argue against this position compliment the hard-hitting descriptions of hardship in the memoir. Edward A Hagan argues that McCourt avoids the cliché of his American Dream narrative through ‘the poignancy of the suffering he details’. However, as Mitchell suggests, this suffering may also be seen as a cliché and stereotype held against the Irish working class. Hagan goes on to suggest that it is particularly Irish critics who find Angela’s Ashes problematic, showing that the divide in the critical reception of Angela’s Ashes can be mapped along national lines. McCourt’s divided identity as an Irish-American author thus makes itself felt through his memoir, inspiring different responses from different parts of the world. Éigeartaigh highlights this struggle between Irish and American identity as “the binary opposition at the heart of McCourt’s text”. Class could be added as another lens through which to view this binary opposition.

McCourt’s own feeling was that he wrote Angela’s Ashes out of a sense of “responsibility to my family and to the people who lived around me.’ He sought, he told Terry Gross in a 2009 National Public Radio interview, to ‘convey the dignity of the people – the way they dealt with adversity and poverty and their good humour.”

Douglas emphasizes that working-class memoirs, including Angela’s Ashes, “opened up literary spaces and language for the narration of working-class childhoods amid alcoholism, mental illness, poverty, and sexual abuse.” Angela’s Ashes was clearly impactful for many readers from working-class backgrounds. In a 1998 interview, McCourt described receiving a letter from a reader in India who said “I was his brother, because he had a poor upbringing.”

McCourt’s tone in describing this anecdote is ironic and perhaps dismissive; it is far from clear that he feels any meaningful affinity with his reader. What it does show, however, is the impact this memoir had, and continues to have, on readers who saw in the poverty and resilience of McCourt’s characters, and in the beauty of his prose, something of themselves.

All donations go towards supporting the Bee’s mission to nurture, publish promote and pay for the best new working-class writing.

Comments